Art In Conversation

WOLFGANG LAIB

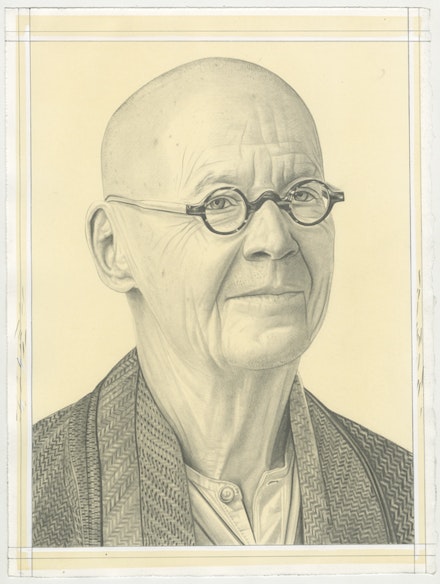

with Phong Bui

PART I

New York

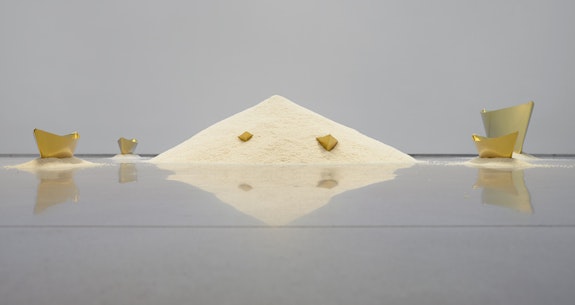

Sperone WestwaterMarch 9 – April 21, 2018

The clarity of thought and simplicity of execution in the work of Wolfgang Laib never fails to transpire feelings of lightness against life’s awesome gravity. I have not forgotten how moved I was when I first encountered his 1995 exhibit at Sperone Westwater, when the gallery was in SoHo (142 Greene Street); the scent of beeswax filled the whole space and led to a series of less than life-size boats cast in wax, resting on high scaffolding, almost near the top of the ceiling. I was thrilled to finally have the chance to meet the artist at the gallery on the occasion of his ninth solo exhibit with the gallery, Where the Land and Water End, which includes sculpture, works on paper, and a site-specific wall drawing.

Phong Bui (Rail): I’m so intrigued and taken by how you still live and work in the same place you were born, in a remote, rural village.

Wolfgang Laib: Yes, a small near village called Biberach in Southern Germany, near Switzerland. It’s about two hours west of Munich, between Munich and the Black Forest. Real country. I prefer a life removed from urban distraction so I can focus on my work. It’s a necessary condition.

Rail: Of course, it corresponds to one of the most striking features or characteristics of your work: namely, the intensity of silence. When I first went to Aggie Gund’s home, where I saw your Rice House (which she later told me she acquired from your show in New York at Sperone Westwater in the ’90s—she had previously acquired a Milkstone from the first exhibition in 1979 which she later donated to MoMA and will be shown at MoMA in the upcoming exhibit Studio Visit: Selected Gifts from Agnes Gund, April 29 – July 22, 2018), it must have been in the Fall of 2007, I immediately felt a particular sense of serenity in relation to the other works of art in her collection, including a Rothko painting. I came to see the difference: while Rothko has his own silence, steeped in the transcendental sides of both emotional tragedy and spiritual ecstasy in the tradition of romanticism—I always felt as though I’m the monk standing in the great Caspar David Friedrich painting The Monk by The Sea. Whereas the energy, or I should say the aura of silence that derived from your Rice House reminded me of a similar silence I experienced in Buddhist temples that my grandmother took me to every weekend growing up in Huế, Vietnam. Do you think that aura of silence was initiated the first time you experienced Brancusi’s studio at the Palais de Tokyo, when you were fifteen?

Laib: Yes, in my childhood Brancusi was very important. My parents were interested in Brancusi and he was considered in our family like a demi-god. I can’t offer you a specific reason except that we all felt strongly something otherworldly in his work. In the ’60s, it was the first time you could see it publicly in Paris, and then in the ’70s the studio was moved to the front of the Centre Pompidou. That was my favorite place for a long time in Paris.

Rail: And what led you to start making art in the middle of medical school?

Laib: I was four years in medical school, and then I did my dissertation for my studies about the hygiene of drinking water in India, where I stayed for half a year. I came back and made my first Brahmanda (Egg of the Universe), which took two or three months to chisel it into shape. It was a black boulder from the region, brought there by glaciers of the ice age, which means it was extremely hard to work on. I made some smaller ones before, but this was the main piece that had a strong spirit in it. I had the fundamental skills of chiseling and carving so I was able to conceive the form very gradually. I began when I came back from India in September, and just before Christmas it was finished. It was a life-changing experience.

Rail: And from that point on you decided to be an artist; but the tension must have existed long before, being caught between the attraction to Eastern culture and the given Western tradition.

Laib: Yes, the tension was always there. My family was always interested in Indian art and culture. In the ’60s, there were some exhibitions that my father saw in Europe of tantric art, abstract drawings and so on from the 16th or 17th century. He thought they were like Mondrians, so he bought a few of these drawings and said, “I want to see the country where this is coming from.” That was his first interest in going to India.

Rail: Your father was also a doctor, who also had been interested in Eastern philosophy through these drawings of tantric art. So it’s fair to say he had a significant role in shaping your own similar interest, particularly in becoming an artist.

Laib: Yes. I lived with my parents half of my life, and three generations lived in the same house, which in many ways is very different from what other people do. We had a big property in Germany, and all three generations slept in the same house. During the day everybody had his or her own house to do their work. My father had much to do with creating this way of life.

Rail: I’d say it’s a very unusual and unique family. When I first met your wife, Carolyn (Reep), she told me while she was working as a conservator-restorer specializing in Asian art, she encountered your first show at Sperone Westwater Fischer in 1979 and decided to come back and spend a whole week of her vacation at the gallery. She eventually met you, and you two corresponded through letters for a few years before getting married. She, too, had a similar affinity towards the East. It seems as though you both may have been Asians in your last incarnations.

Laib: It’s possible.

Rail: Then there’s of course the indispensable issue of healing, which medicine and art have in common.

Laib: I always felt when I made my first Milkstone in 1975 it was a direct response to what art can do where medicine can’t. People often ask, “What do your medical studies have to do with art?” I feel I never changed my profession; I just put in my artwork what I wanted to do as a doctor. But I realized in medicine, which is mainly natural science, I couldn’t do what I wanted to do as an artist. I was searching for some form of harmony through these differences.

Rail: I think this is exactly what sets you apart from Joseph Beuys. While at first you and Beuys share a similar interest in healing, Beuys’s shamanistic investment in alchemy and Rudolf Steiner’s philosophy, among other things, are different from your medical studies as a natural science and your vast interest in Eastern philosophies, including Taoism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and so on. Not to mention the political component to Beuys’s work, which is tied to the tumult of German history and his upbringing. Whereas in your work, it’s apolitical.

Laib: I would not be a member of the Green Party, or any kind of party. Also, my goals lie more in the long-term. I think something which does not look political at all at first in the long run is very political. For example, Lao Tse’s text The Great Silence, which is about 2,500 years old. I think that Lao Tse was very political. He was an obvious challenge, not only to the politicians and the social and political conditions of his time, but continues to be a challenge now.

Rail: To be political also means a testament of independence.

Laib: Yes, that’s very political. One can say that Lao Tse was political in the same way that the Buddha was. That’s also what I feel about important art and cultural statements—it’s not only for answering Mr. (Donald J.) Trump. It goes far beyond any president who is president right now. When I made the wax chamber work, Wax Room (Where have you gone—where are you going?) in 2013 at The Phillips Collection, when it was in production, the German ambassador was very kind and made a big reception in the German Embassy in Washington, D.C. for me. When I arrived with Klaus Ottmann, the curator of the show, at first he was very diplomatic and polite, but then couldn’t help but say, “Mr. Laib, normally we have only receptions for politicians, economists, or businessmen from the big German companies, etc. etc. Culture is only considered our hobby.” Klaus, who stood next to me, was afraid that I would take a taxi and leave, but I didn’t. Klaus, in response to the ambassador, said, “Listen, culture is not a hobby. This wax chamber will survive Barack Obama (who was just sworn in in January of that year) and many presidents after him.” [Laughs.]

Rail: It’s a certainty. To go back to the issue of silence, I remember when I was a child, being a Buddhist, my grandmother would take me to a local temple in Huế, Vietnam. I remember there was a mural of the Buddha in profile sitting under the Bodhi tree. In front, on his left, the demon Mara, Buddha’s tormentor, after having failed to seduce him by sending his three daughters, shot volleys of arrows at him, which went right through his torso and turned into adoring bouquets of flowers behind his back. I remember asking my grandmother, “Why didn’t the arrows stop at his torso and kill him?” Her answer was, “They couldn’t kill him because he was not there.”

Laib: Whatever there was, just only his physical body.

Rail: The spirit and the soul are not home. [Laughs.] Exactly, this is what the word “nirvana” means.

Laib: Yes, the lightness of being.

Rail: Which requires silence. And the notion of silence in the East is far different from the West. I don’t know how you feel, Wolfgang, but the first time I saw a crucifix, I was traumatized by such a dramatic and shocking image—Jesus Christ is almost more than half naked, a crown of thorns on his head, his hands and legs nailed into the cross, hence his whole body is pulled from the weight of gravity while being covered in blood…It’s a very anxious and traumatic image.

Laib: It’s amazing how you describe it, because for us it’s such a normal image that you don’t even think of whether he is naked or not. We’re so used to seeing it we don’t even think about it anymore. And concerning silence—I learned much living in Asian countries. The frieze with the white drawings in this exhibit has one drawing with a quote by Lao Tse: “ […] rare indeed are those who are still, rare indeed are those who are silent and rare indeed are those who obtain the bounty of this world.”

Rail: Maybe I can say the same of Buddha meditating under the Bodhi tree, who essentially is not there, hence generating a calming and serene tremor. And the emphasis is his right hand touching the earth, which implies the moment of his enlightenment. So being close to the earth is essential. This is why most Asians prefer working, eating, and sleeping on the floor. The first time the French came to Vietnam, in the mid-19th century, they called us squatting monkeys. The insult is a complete misreading.

Laib: I was immediately attracted to being close to the earth, as were my parents. My parents built this glass house in the late’50s, but after our first trip to Turkey, where we saw the tomb of (Jalal-ud-Din) Rumi in Konya, and how people lived with uncluttered and simple, almost empty spaces in their homes; there were only a few pillows on the floor. That was for my family and me something so incredible to see. We had only art and our own bodies. Furniture would be very disturbing. I mean, these two chairs, they look so ridiculous. [Points from where we are sitting on the gallery floor to the chairs.] They disturb the whole space. I mean if you sit on the floor, eat on the floor, you can really have a space, not disturbed by any interference.

Rail: This seems to relate to the aura of Brancusi’s studio in your first visit to Paris, then later in the same year when you visited Târgu Jiu where you saw his Endless Column, The Gate of the Kiss, and especially The Table of Silence, which I feel is the closest in spirit to your work, is that a fair observation?

Laib: Yes, I think so. It was a natural attraction to, again, the closeness to the earth as you had just described.

Rail: Which is different from the elimination of the base, ever since what Carl Andre had done as a logical consequence with Brancusi’s assimilation of the base as part of the sculpture. Carl’s mediation with the floor seems to be an intellectual and visceral retort, whereas one gets the feeling in your case it is a spiritual and natural inclination. Do you think your study of Buddhist Sanskrit has heightened this particular learning?

Laib: Yes, I managed to study Sanskrit during my medical studies at the University of Tübingen, which is known as one of the best universities in Germany for the study of medicine, law, and theology.

Rail: Karl Barth and Paul Tillich had gone to school there.

Laib: And before them (Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph) Schelling, and others. There were very famous Indologists like Otto Glasenapp, Paul Thieme, Heinrich von Stietencron, and others teaching there at the time, and I was lucky to have studied with them because not every university in Europe offers Sanskrit studies. So, then I realized that German philosophers had been interested in Indian philosophy since the mid-19th century.

Rail: Beginning with (Arthur) Schopenhauer, certainly with his interest in the Four Noble Truths: suffering, the cause of suffering, the end of suffering, and the path.

Laib: Yes, and to [Hermann] Hesse, and also myself. The last time I went to India I realized that it is not by chance that German philosophers are so interested in Indian philosophy. Life, death, temporary life, and end of life in Indian philosophy are very close to Schelling and Schopenhauer. They were among the first to translate the Upanishads and other Indian philosophy into European languages—that’s not by accident. Also, having studied medicine and being interested in what life and death mean from a Western perspective, by the time I found my way with the Upanishads, I felt natural to take the latter path and be an artist instead of a doctor.

Rail: Since most of your critics tend to agree that, apart from the similar liberation from the pedestal which you share with Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Richard Serra, Ulrich Rückriem, among others, it’s the healing elements, as Tom McEvilley referred to as the “magico-therapeutic,” that brings you closer to Beuys. When in fact did you discover Joseph Beuys’s work?

Laib: Actually, when I began my medical studies, I was working in my first year of a medical residency in a local hospital, in a nearby town, in which all the nurses were nuns. One of them always said to me, “You should have the name Joseph because you are such a dedicated worker. You are not just a doctor.”

Rail: Oh yeah, we shouldn’t forget that Joseph is the patron saint of workers, laborers, and of social justice.

Laib: At any rate, two patients died so I went to their funerals, which is unusual because doctors don’t usually attend the funeral of one of their patients. There was this nun who had a white box with all the materials which she used when somebody passed away—big pieces of white cloth to cover the body, several crosses, among other memorabilia. And I remember that this box looked like one of Beuys’s boxes. And at the time I’d just discovered Beuys’s work, and I remember very well how I compare that white box to Beuys’s own. For me it was even more straightforward as my very first time seeing a patient dying in a hospital, with a nun nearby wearing a tunic with a rope around her waist. It was also right from the beginning of my medical studies there was this confrontation of the natural sciences and the fragility of life, which quickly brought me to become interested in Indian philosophy, especially with Jain texts, because in regard to non-violence, they were even more radical than Buddhism. I managed to study with a professor who was a specialist of Jainism. So on one side there was the physical, medicine, dead bodies and so on, and on the other, the Jain texts that stress an asceticism and reincarnation, among other things, and every living thing is an individual and eternal soul, which somehow brought everything together very clearly for my life’s purpose at the time.

Rail: Did you meet Beuys eventually?

Laib: Yes, I drove seven hours from Biberach to Düsseldorf to attend his opening at Konrad Fischer in the late Winter of 1983. I remember the whole gallery, walls, ceiling, and floor were covered with huge sheets of lead. There were also two silver rings and a lightbulb hung in the middle of the ceiling. The whole gallery was packed with hundreds of people wanting to talk to him. I thought he wouldn’t recognize me and I didn’t want to disturb him. But as soon as he saw me, he came like an arrow to me. And right away he asked me about my Milkstones because he had heard and maybe seen my big Milkstone and a pollen square at the German pavilion one year before at the Venice Biennale.

Rail: In 1982.

Laib: Exactly. It was quite a pressure because I was only thirty-years-old at the time. Anyway, there’s also another serious connection—Beuys died the same day my daughter Chandra (Maria Sobeide) was born, on January 23, 1986.

Rail: Whoa, an augury of surprise. On a similar front it’s interesting because of the notion of spirit, which derives from the last breath of a dying person: if a life of a person is lived unfulfilled, the spirit lingers like a ghost. The Greeks believed it’s the spirit that needs to negotiate, mediate with all five senses in order to give a report to the soul. If in fact Beuys’s selections of such specific materials including iron, felt, fat, honey, etc. that all have specific meanings in his alchemical functions, how would you describe your own selections of materials such as stone, beeswax, rice, pollen, and milk, for example? Each of these materials, once shaped or applied to a form, embody the spirit of the things, as they say.

Laib: I was always very careful in my choices of materials. It took me a long time to choose each material to work with, simply because I would explore it for a few years. I began the first Milkstone in ’75; worked with pollen in ’77; rice in ’83; beeswax in ’87; then made the first wax chamber a year later, and so on. I find each material has its own beauty and nurturing elements, which relate to the cycles of life and death, and the ephemeral and eternal. Each requires a ritual of intense labor.

Rail: Like how the Milkstone requires cleaning and the white marble slab must be refilled with fresh milk everyday. Or how you collect your pollen from the meadow near your home in the Spring and late Fall.

Laib: I learned how to make work without a studio in the beginning. Also, I can and have reworked many years later with the similar form and materials which I found very beautiful.

Rail: Oh no, you’re not interested in creating new objects of mass consumption! [Laughter.]

Laib: I suppose I’m the opposite. I find it beautiful to collect pollen, for example, even forty years later. I mean if you want to do something lasting and significant, you could have done it 10,000 years ago or 10,000 years from now. This has nothing to do with fashion. [Laughter.]

Rail: Do you believe in reincarnation?

Laib: Yes, I do. As a doctor, I’ve seen the body come into being, then die, and disappear; but the soul is coming from somewhere and is going somewhere else. That is the limit the doctor doesn’t know.

Rail: That’s how we communicate with the work of art because it contains the spirit and the soul of the maker, the artist. Looking at this white oil pastel mural, Vom Krug deiner Liebe / Schwimmt meine Seele / Und gebrochen ist alles / Irdische meines Körpers (Jalal-ud-Din Rumi) (2018), made site-specifically for this show, of endless waves on the white walls, I feel a particular serenity in the silence of the image. There’s also a rhythm to their irregular contours from one wave to the next. The experience is so ephemeral.

Laib: Our life is ephemeral, our body is ephemeral. But then that is what connects me to the beginning; I began to study medicine because I thought this is about our ephemeral life but then I discovered I can explore this ephemeral world, which I think is the eternal, which goes beyond your individual body, and is hence connected to the universe. This is something that I learned from Asian culture. That is not the perspective embraced by the Greek and Roman culture in which the hero is usually personified by the physical body, and once the body dies, it is seen as a tragedy.

Rail: I know you made a second Brahmanda to commemorate the 700th anniversary of the birth of Rumi, and placed it near the entrance of his tomb, at the Mevlana Museum in Konya, Turkey. Rumi is one of my favorite poets.

Laib: In fact, the wall drawing in this exhibit has the quote by Rumi, as we mentioned before: I wrote it here in to the drawing in German: “vom Krug deiner Liebe / schwimmt meine Seele / und gebrochen / ist alles Irdische meines Körpers,” and the English translation would be: “From the cup of your divine love / my soul is swimming / and dissolved is all / the earthliness of my body.”

Rail: Beautiful! I also remember a few lines in regard to the search of the eternal and ends with silence: “Do not run away / Run inward, as / unripe grapes run towards their own sweetness.” …. Then it picks up somewhere in the middle, “I want that Love to move the mountains / I want that Love to split the oceans / I want that Love that made the wind tremble / I want that Love that roared like thunder / I want that Love that will raise the dead / I want that Love that lifts us to ecstasy / I want that Love that is the silence of Eternity.”

Laib: Silence can also mean immensity of the opposite intimacy.

Rail: Or glimpses of invisibility. I remember at the end of an interview we did with Carl Andre in the Rail [published in February 2012] when he was asked what was his most memorable moment of his life as an artist. His response was, if he had the miraculous power, he would send everyone to his 1970 show at the Guggenheim, partly because when the viewers stood in the middle of 37th Piece of Work and looked up at the museum’s rotunda, he or she was the spiral—one couldn’t see his work at all. Carl also said his work is similar to what Bob Ryman does in his near invisible paintings.

Laib: Less is more, like haiku poems.

Rail: It encourages one to fill the rest of the space with one’s own imagination, which is the domain of scale—an essential issue in your work.

Laib: Yes, as you know I made very small pieces as well as monumental works like the ziggurat pieces made of beeswax. The first exhibition I made together with Harald Szeemann was at the Kunsthaus Zürich in a 1985 group show called Spuren, Skulpturen und Monumente ihrer präzisen Reise (Traces, Sculpture and Monuments of Their Precise Voyage) and he wanted to have a pollen piece, and I said “I’ve just made this row of five mountains and the title is The Five Mountains Not to Climb On (1984),” which consists of five small mounds of pollen. And I realized immediately how this was turning his head around. It was a huge exhibition that included Brancusi, Giacometti, Medardo Rosso, Cy Twombly, Louise Bourgeois, Richard Tuttle, and others. And at the opening he spoke only about The Five Mountains Not to Climb On and that was for him a good example of and about scale. This piece united our visions where we realized our perspectives of this world can be captured in these small mountains. In other words, small objects can generate big scale.

Rail: As long as it embodies the artist’s spirit, as we spoke earlier. I’d also say of the opposite: big objects can have small scale of intimacy.

Laib: Yes. In bigger exhibitions I often combined big works like the beeswax ziggurat, which is about six meters high (nearly 18 feet), with the five small pollen mountains very close by.

Rail: Can you share with us how the concept of this show came about?

Laib: I’ve been making these Brahmandas in Southern India, near Madurai, since 2010. I have maintained a studio there since 2006. Close by, in this region, are these huge, bare granite hills and I had the vision I would like to make a huge Brahmanda in one of these hills, like the way they used to carve temples from the top down out of the mountain, for example, Kailasanatha Temple, Ellora and Ajanta in Maharashtra. I find that very beautiful. I would try to use a similar technique and instead of placing the huge Brahmanda on top of a mountain, which would be violating and intrusive, I would carve out a rectangular space inside the mountain and then have the Brahmanda (which would measure about 60 feet in length) placed in it as though it was being born out of the mountain. It wouldn’t be visible from a distance nor from the side, and it also wouldn’t disturb the shape of the mountain. I do hope to still realize this this dream …

Rail: What about the frieze-like works on paper, Where the Land and Water End (2017), which correspond to the site-specific wall paintings?

Laib: Yes, they do in concept, except these are portable works of art. There’s different texts from the Tao Te Ching, from the Upanishads, also an Italian text which exists in many other Italians churches, but it’s carved on the cadaver tomb below of the Trinity scene of Masaccio’s famous fresco The Holy Trinity at Santa Maria Novella in Florence. In English: “I once was what you are and I am what you also will be.” It’s very Indian. It’s like saying “I was where you are now and am now dead, where you soon will be.” Very serious, right?

Rail: We won’t have to worry too much since we both believe in reincarnation.

Laib: Yes, in this life I didn’t become a doctor as I had tried. I became an artist instead. Maybe in my next life I’ll come back as an artist again.