BLUE OR FALSE?

With poison frogs becoming increasingly more popular, it has never been more important to know your animals’ roots.

New scientific developments have found that human limb-regeneration treatments may be closer than we think.

www.exoticskeeper.com • july 2022 • £3.99

EXOTICS NEWS • COLLARED LIZARD • KEEPER BASICS - FISH HEALTH • ENRICHMENT • BEE-EATERS

OF THE RAINFOREST

OUTSIDE THE BOX

Identifying and caring for Indonesian blue-tongue skinks

LEGENDS

Bushmasters are some of the largest venomous snakes on earth. Find out how ZSL London Zoo managed to breed these incredible animals. TINC

A SHOCKING DISCOVERY

CONTACT US

EDITORIAL ENQUIRIES

hello@exoticskeeper.com

SYNDICATION & PERMISSIONS scott@exoticskeeper.com

ADVERTISING

advertising@exoticskeeper.com

About us

MAGAZINE PUBLISHED BY

Peregrine Livefoods Ltd

Rolls Farm Barns

Hastingwood Road

Essex CM5 0EN

Print ISSN: 2634-4691

Digital ISSN: 2634-4688

EDITORIAL:

Thomas Marriott

Aimee Jones

DESIGN:

Scott Giarnese

Amy Mather

Subscriptions

Follow us

This issue of Exotics Keeper Magazine has been a pure joy to work on. The team at ZSL London Zoo have provided some very unique insight into one of the world’s most cryptic venomous snakes. As well as the full-length feature in this magazine, readers should head over to our social media channels to watch a tour of the exhibit and check out the interview. Dr Michael Levin also talked us through bioelectricity and the future of human limb regeneration (which doesn’t seem that far away!) We also take a look at the subtle differences between the blue-tongue subspecies and how this might impact keepers. Finally, we look at just some the huge spectrum of ‘tincs’ in the Guiana Shield. This month our ‘Keeper Basics’ section comes from renowned aquarist and author Dr David Pool on the subject of ‘fish health’.

The world of exotics keeping has

keepers know how to rehome their animals in a way that does not bring harm to the animal or the wider ecosystem. Anyone concerned about the welfare of an exotic animal should contact their local rescue centre immediately. Whilst

Every effort is made to ensure the material published in EK Magazine is reliable and accurate. However, the publisher can accept no responsibility for the claims made by advertisers, manufacturers or contributors. Readers are advised to check any claims themselves before acting on this advice. Copyright belongs to the publishers and no part of the magazine can be reproduced without written permission.

Front cover: Eastern blue tongue skink (Tiliqua scincoides

Right: Eastern blue tongue skink (Tiliqua scincoides

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

DRY FOODS, FORMULAS & SUPPLEMENTS

High

Ideal for species which, in the wild, consume a significant amount of fruits and seeds from oleaginous plants (genera Psittacus, Ara, Poicephalus).

Available in 800g, 3Kg and 12Kg bags Energy

02 06 16

02 EXOTICS NEWS The latest from the world of exotic pet keeping.

06 BLUE OR FALSE? Identifying and caring for Indonesian blue-tongue skinks.

14 SPECIES SPOTLIGHT Focus on the wonderful world of exotic pets. This month it’s Collared lizards (Crotaphytus collaris).

16 TINC OUTSIDE THE BOX Dendrobates tinctorius in the wild.

33 35 39

26

CROSSING THE POND Zen Habitats launches in the UK .

33LEGENDS OF THE RAINFOREST

Few snakes are as mysterious and impressive as the bushmaster.

35SHOCKING DISCOVERIES FOR LIMB RE-GROWTH Human limb-regeneration treatments may be closer than we think.

39 KEEPER BASICS: The EK guide to fish health and water quality.

45 FASCINATING FACTS Did you know...?

46 ENRICHMENT IDEAS Monthly tips on how to enrich the life of your pet.

EXOTICS NEWS

The latest from the world of exotic animals

New Orang-Utan Habitat

A new outside habitat has been completed at Dudley Zoo & Castle. The extension, attached to their original indoor facility, has been completed at a cost of £500,000. The large grassy area is fitted out with a range of climbing poles and ropes etc… and is now home to all four Bornean orang-utans - “Jazz”, “Sprout”, “Djimat” and “Benji”. Elsewhere in the zoo the first five naked mole-rats have been born to the new colony which arrived in 2018.

Here 140 Tequila Splitfin (Zoogoneticus tequila) have been installed, with some Golden Skiffia or Golden Splitfin (Skiffia francescae) to be added in due course. The goodeid species are extremely rare and in some cases extinct in the wild, but are quite easily bred in captivity - being live-bearing species, and they can be kept privately by individuals belonging to the Goodeid Working Group. This allows other people to become actively involved in contributing to the conservation of this rare group of fishes.

European Zoos” and more recently, in May 2022, “A Legacy of Shame –Elephants in Zoos”. The giraffe report focuses on the welfare, nutrition, social behaviour and stereotypical behaviours (mainly oral) of giraffe in captivity. In addition the infamous EAZA/ Copenhagen Zoo situation, regarding the giraffe “Marius”, was chosen as an individual example of bad practice.

Rare Fish Get New Natural Pool

Tropiquaria, at Watchet, have long been home to several Critically Endangered goodeid fish species, as a member of the Goodeid Working Group, and in cooperation with other collections. Now a new, more natural, pond has been created for two of those species in the tropical house at the collection.

The Goodeid Working Group is a non-profitable international Working Group managed and run on a 100% voluntary basis. It was established on 1st May, 2009 in Stockholm, Denmark in response to the critical environmental issues facing the majority of wild Goodeid species/populations, plus the poorly-documented ‘disappearance’ of many captive collections. The primary goal of the Goodeid Working Group is to “promote collaboration between like-minded hobbyists, universities, public aquaria, zoos, museums and conservation projects in order to maintain aquarium populations of Goodeids while assisting in preservation of remaining natural habitats”. Goodeids are fish endemic to Mexico and some areas of the United States, the family contains about 50 species within 18 genera and is named after ichthyologist George Brown Goode.

The Giraffe/Elephant BFF Reports

In the last year or so the anti-zoo group the “Born Free Foundation” (BFF) has recently published two reports, the first in February 2021 called “Confined Giants - The Plight of Giraffe in

According to the BFF there are currently 580 elephants in European zoos, with 49 elephants in U.K. zoos. The elephant report is backed by some well-known names, as is often the case; Damian Aspinall - Chairman of the Aspinall Foundation, Angela Sheldrick CEO of the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust and the naturalist and broadcaster Chris Packham. The BFF are calling for the “capture of wild elephants for display must stop and breeding in captivity should end”. However those that remain in captivity should be provided with the best possible conditions for the rest of their lives. Angela Sheldrick said “The report uses individual case studies to outline the history and continuing plight of captive elephants. Revealing the impact of captivity on their physical and psychological health”. Stating that “40% of infant elephants in zoos die before they reach the age of five” and that “no zoo in the world can provide elephants with the complex social structures and vast spaces they need to thrive”. Chris Packham said “The attempted captive breeding and capture of wild elephants to be imprisoned in zoos is plain wrong and here is all the evidence to prove it”. “A tragic catalogue of inhumanity wrought upon a creature we claim to love”. “It must end today” he said.

In response Jamie Christon CEO of Chester Zoo said “The Born Free report draws on outdated data and

2 JULY 2022 Exotics News

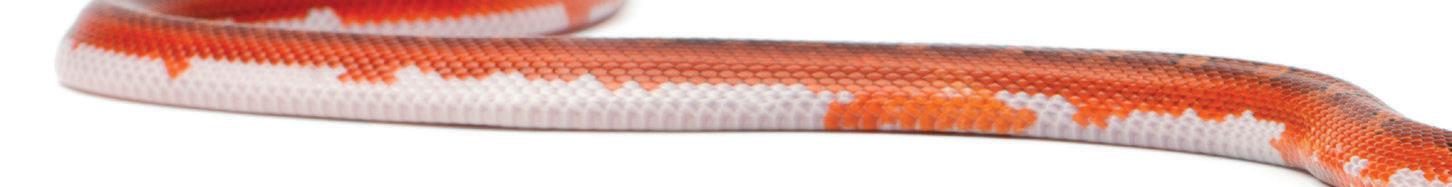

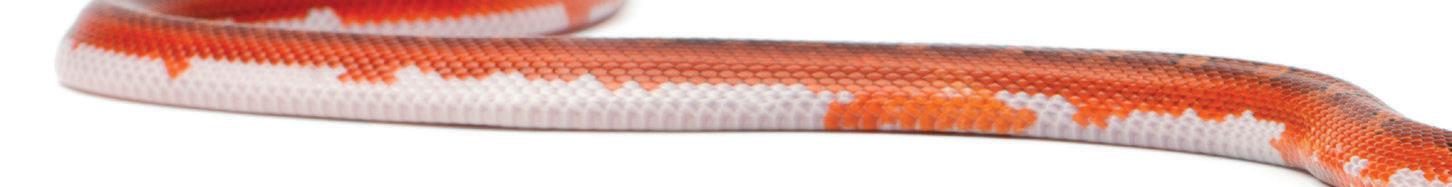

Unlike this corn snake, we have sliding scales...

©Dudley Zoo & Castle

Tequila Splitfin (Zoogoneticus tequila) ©The Goodeid Working Group

information, referring to practices which simply do not take place in modern U.K. zoos”. “Born Free paint a picture of how some zoos were over 50 years ago – but conservation-focused zoos like ours are now a million miles away from that” he said.

“The report highlights a number of things to improve welfare standards for elephants” he added. “We`ve actually been implementing these for many years, it is already part of zoo best practice” “If anything, the bar Born Free set is quite low” “we pursue world-class standards of animal care and have been exceeding what`s in the report for a long time”.

summer. The hotel also has a timed lighting system to avoid disturbing the glowing females. Glowworms are not worms but beetles and only the flightless female glows, to attract a male on summer nights. Although the males fly, the species is notoriously bad at dispersing, and so becomes trapped in small areas of suitable habitat. The larvae is a gardener’s friend, being a voracious predators of snails.

Spixs`s Macaw Release

UK Glowworm Release

More than 500 captive-bred glowworm larvae (Lampyris noctiluca) have been released in the grounds of Elvetham Hotel in Hampshire and Cornwall by ecologist and conservationist Peter Cooper, in an effort to revive this declining species.

Further batches of larvae (totalling 596) and some adults will be released again in the same place this year and at Combeshead in Cornwall – a rewilding and glamping site run by Derek Gow. The four-year project is led by ecologist Derek Gow, who has been working on several rewilding projects including water voles, beavers and wild cats. Peter, who works for Derek Gow, was already breeding glowworms with a method he perfected during the pandemic, assisted by YouTube tutorials from a glowworm keeper in Germany. Glowworm larvae are kept on a bed of coconut fibre in plastic takeaway tubs with a damp sponge to retain moisture, and fed fresh snails – also bred for the purpose – every day during their growing season. Peter has even taken the glowworms with him in a cool-bag when travelling for work, so he can keep an eye on them and satisfy their voracious appetite for snails. The gardener at Elvetham has been collecting snails and leaving them in the release-zone for the larvae that will be released. These larvae will reach maturity and glow next

In a ground-breaking event, eight Critically Endangered Spixs`s macaws – the world`s rarest bird, were released into the wild from the Spixs`s Macaw Release Centre`s holding aviaries at Curaca, Brazil on the 11th June into the Caatinga region. These birds were fitted with radiotracking collars and were released alongside eight Illger`s macaws which have spent the last few months living with the Spixs`s macaws and will help them get used to the unfamiliar environment.

In March 2020 52 Spixs`s macaws – out of a flock of 170 birds, were sent from the private parrot breeding facility to the Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP) in Berlin, Germany via Berlin Airport, courtesy of Crossborder Animal Services specialist transport, to Curaca in North-eastern Brazil. Here they have spent the last two years living in the release aviaries and in 2021 they have produced three more chicks in these aviaries. Most of the world captive population, of about 200 birds, were kept at Pairi Daiza Zoo in Belgium and the Association for the Conservation of Threatened Parrots (ACTP). Both collections have bred numerous Spixs`s macaws between them.

The total number of Spixs`s macaws at the site at Curaca was 55 birds, but some will be retained for further breeding and future potential releases in the on-going release programme. At the end of 2022 it is planned to release a further 12 Spixs`s macaws into the same area.

Flexible exotic insurance for every budget. Get a quote at britishpetinsurance.co.uk or call us on 01444 708840

3 JULY 2022 Exotics News

Peter Cooper releasing the glowworm larvae ©P Cooper

New Snake in Paraguay

A team of researchers in Paraguay have scientifically described a new species of snake.

A juvenile specimen of Phalotris shawnella, was captured, but later escaped. “This individual was originally discovered by chance when digging a hole at Rancho Laguna Blanca” said co-author Jean-Paul Brouard - an expert with the Paraguayan NGO Para La Tierra.

Phalotris is a group of small to medium-sized, semifossorial snakes in the family Colubridae. Phalotris shawnella is particularly attractive and can be distinguished from other related species by its red head, a yellow collar, a black lateral band, and orange ventral scales with irregular black spots. The species is endemic to the Cerrado forests in the San Pedro region of northeastern Paraguay.

These snakes were first described in 1862, and are noted for their striking coloration with red, black, and yellow patterns. They are distributed largely in open areas of Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Argentina. There are currently 15 species of Phalotris currently recognized,

separated into three species groups: the tricolor group of five species, the bilineatus group with four species, and the nasutus group which includes six species. The newly-described species, Phalotris shawnella, belongs to the nasutus group.

New Indian Species Discovered

A new species of non-venomous snake has been discovered at a height of over 1,700 metres above sea level in Murlen National Park, Mizoram, in the Champai District of North-eastern India. Unlike its six “sister-species” this new snake has been found well-away from water sources and is the only one of its genus to be found at this height. It has been named Herpetoreas murlen after the Murlen National Park.

The new species features a dark olive-grey body, randomly-speckled scales with black on the borders, interscales speckled sparsely with white, and a dorsolateral stripe reaching from the neck to the tail.

It is closest genetically to Herpetoreas burbrinki, its Chinese cousin.

ON THE WEB

Websites | Social media | Published research

Each month we highlight a favourite website or social media page

THIS MONTH IT’S: BIAZA

The British and Irish Association of Zoos and Aquariums (BIAZA) is the professional body representing the best zoos and aquariums in the UK and Ireland. They have more than 100 zoo and aquarium members whom they support in their commitment to be at the forefront of conservation, education and research. www.biaza.org.uk

4 JULY 2022

Exotics News

Collated and written by Paul Irven.

©Jean-Paul Brouard

©Novataxa

BLUE OR FALSE?

Identifying and caring for Indonesian blue-tongue skinks.

6

Tanimbar blue-tongue skink (Tiliqua scincoides chimaerea)

Tanimbar blue-tongue skink (Tiliqua scincoides chimaerea)

Blue-tongue skinks have been popular pets for decades. Seven separate species make up the Tiliqua genus, which includes the shingleback lizards (T. rugosa) and the pygmy blue-tongue (T. adelaidensis) of Australia. However, this genus is most characterised by the bulky, smooth-skinned and perpetually “chill” blue-tongue skinks of Australia and Indonesia. Historically, Australian blue-tongue varieties were very popular and morph breeding in the US opened an entire subculture of keepers dedicating their time to producing these impressive animals. Now, in the UK the most dominant pet species is T. gigas, commonly known as the Indonesian or “giant” blue-tongue skink. This species inhabits the tropical forests of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the surrounding islands. Not only are these animals different to their Aussie cousins, but speciation has led to three distinct subspecies, with several ‘locales’ regularly exported to the UK over the last 40+ years. Over that time, crossbreeding between locales has likely happened, but a better understanding of the distinctions between each population will undoubtedly improve the husbandry of these loveable lizards.

Indonesian blue-tongue skink

Tiliqua gigas gigas is the nominate form of this species. However, due to its distribution, island ‘locales’ have evolved in isolation from one another for millions of years. This means that although the Indonesian blue tongue skink is a distinct species, further studies into each population have described several subspecies. There are bound to be more identified as taxonomists continue to study these populations, but for now, these unique animals are referred to as ‘locales’. Some of these locales are already widely available in captivity and are as follows…

Halmahera: The Halmahera blue tongue skink is a subspecies of T. gigas that is found only on the Halmahera Island in North Indonesia. Distinguishable by their red/ grey colouration and thin dark markings as well as a different scale structure around the eye, this is a unique variation on the nominate form. Caring for Halmahera blue-tongues should be identical to other island forms of T. gigas. Although many animals with black banding

are listed as ‘Halmahera’ regardless of their lineage, in the wild this species would be exposed to the highest levels of humidity of any blue tongue species. Keepers should average around 70% RH, with daily spikes up to 100%. This contrasts with other T. gigas found on more southernly islands which tend to thrive at 50% with spikes of 80% humidity.

Irian Jaya: Irian Jaya is the name given to the Indonesian (Western) side of Papua and adjacent islands. It is a huge landmass with a vast spectrum of biotopes and climates. Although the ‘Irian Jaya’ blue-tongue is taxonomically incomplete, it is widely believed this species thrives in lower-humidity environments when compared to other island forms. They are variable in their patterning and not always easy to distinguish from other subspecies or locales. This has led some people to believe it is a cross between the Tiliqua gigas species of Indonesia and the Tiliqua scincoides (Eastern) species of Australia, from when there was a land bridge between the two countries.

8 JULY 2022 Blue of False?

The Kei Island blue-tongue skink

Tiliqua gigas keiensis

The ‘Kei Island’ blue tongue originates (unsurprisingly) from the Kei Islands of Maluku in Indonesia and perhaps the neighbouring Aru Islands. These islands are part of Wallacea and sit at a Northernly position in the bluetongue skinks range, suggesting that high humidity and a tropical environment will provide optimal care. They are a very robust subspecies of T. gigas and are characterised by their orange base with speckled patterns that stretches from their head and down their torso. Juveniles will develop these patterns at around 3-6 months of age. Their unique appearance prompted the distinction of this subspecies back in 1894 and since then the islands changed their name from “Key” to the colloquial “Kei” spelling, with the scientific name ‘keyensis’ following suit. They are reported to be one of the more aggressive subspecies of blue-tongue though this could be because

most of the animals in the hobby are wild-caught. Captive breeding of this species has been successful in the US, but as blue-tongues are not prolific breeders, they are still reasonably rare in the UK and Europe.

The faded blue-tongue skink

Tiliqua gigas merauke

Pronounced mer-oo-kee, T. g. Merauke (sometimes referred to as the ‘faded’ blue-tongue) is the longest subspecies of the Indonesian blue-tongue skinks. They inhabit transitional coastal plains of Irian Jaya, suggesting they require a reasonably low humidity (around 60%) and may benefit from drier elements in the composition of their substrate. These huge lizards can reach up to 70cm in length and often have extremely good temperaments, making them one of the more popular subspecies available. They are routinely captive-bred across the world.

9 JULY 2022

Blue of False?

The faded blue-tongue skink (Tiliqua gigas merauke)

However, these animals may not be true Merauke’s as this species shares its distribution with other locales of the nominate form and can be extremely variable in colour. In fact, the concept of a ‘true Merauke’ is hotly contested across herpetologist circles, with many researchers believing this is just another colour form of the Indonesian blue tongue, T. gigas.

The ‘other’ blue-tongues

There are several other species of blue-tongue found across Australia which have their own subspecies, colour morphs and locales. The Eastern (Tiliqua scincoides) and Northern (T. s. intermedia) blue-tongues are most commonly seen in the pet industry, but due to export restrictions are generally less widespread in the hobby than their Indonesian counterparts. However, there is one subspecies of the Eastern blue-tongue which inhabits the Tanimbar Islands of Maluku, Indonesia. Tiliqua scincoides chimaerea, the Tanimbar blue-tongue skink has an incredibly glossy appearance, small body and fierce attitude. Tanimbars have very firm bodies compared with other blue-tongue species with faded streaks down their

back. Their name comes from Chimera, a mythical firebreathing dragon. Herpetologists are still unsure why the blue-tongues on this island have evolved such firm bodies and feisty attitudes, predicting that there may be a specific predator or higher density of predators on the island that this species needs to contend with.

Keepers should be extremely vigilant in understanding exactly what species of blue-tongue skink they are caring for. Although these animals are not readily available in the UK, the blotched alpine locality of the Eastern blue-tongue (Tiliqua scincoides) can tolerate extremely cold conditions and inhabit areas that are frequented by snow. The Central blue-tongue, on the other hand, thrives in the heart of Australia where temperatures can reach upwards of 40°C. As these are completely distinct species (as opposed to the subspecies and island localities of T. gigas), they are easily distinguishable. It would be very difficult for someone to source a Centralian blue-tongue for a similar price as a ‘Northern’. Yet, it would not be out of the realms of possibility for an animal to be rehomed under the ‘bluetongue’ banner and a novice keeper to believe all species are synonymous. Naturally, these specialist species require entirely different environmental parameters to T. gigas sp.

10 JULY 2022

Centralian blue-tongue skink (Tiliqua multifasciata)

Indonesian blue-tongue care

Blue-tongue skinks often have docile personalities and have made excellent pets for decades now. They are routinely bred in captivity but continue to be imported from the wild in small numbers, which supports bloodlines with sturdy genetics and healthy animals. As females are viviparous and produce just a few large, stocky offspring once a year, the availability of this species can be sporadic. It has also meant that prices for T. gigas have risen sharply in the last 10/15 years now their appeal as pets have become well-established.

Another appeal of this species in captivity is its omnivorous feeding habits. Juveniles will tend to eat a larger ratio of meat to vegetables, but this should even out to around 50:50 as the animal reaches sexual maturity around two years old. Dedicated ‘blue-tongue’ diets exist, but eggs, rodents, mince/dog food and a wide variety of insects can be used. Blue-tongues are known for enjoying soft-bodied prey, but keepers should be wary that they can become picky-feeders if they are constantly fed a single, rich food source.

blue-tongues in, we’ve given them a brilliant high-energy diet to ensure they’re fit and healthy before they’re sold on. This consists usually of raw or scrambled eggs, with crushed crickets and locusts and some berries too. We’ve also found that they love Repashy Blue-tongue Buffet and this tends to support their health over time too. We also frequently provide snails, which they love! People often make the mistake of just throwing a few crickets into a bluetongue enclosure and that doesn’t work long-term. They need a varied diet, this is extremely important to them.”

Blue-tongues, like all other reptiles and amphibians, should have access to UV but their cryptic behaviours can make this difficult to assess. They are diurnal and hail from the tropics suggesting they need high UVI, but they are also terrestrial, living amongst high grasses or the forest floor and probably receive much lower exposure than other animals in the same biotope. Some island forms will inhabit coastal plains (mimicking the grassland environments of their Australian cousins), while others will thrive in dense rainforest. Although Tiliqua scincoides is considered a Ferguson Zone 2-3 animal, T. gigas is yet to be officially categorised. Applying this logic, whilst also providing plenty of hides and foliage would be recommended.

11 JULY 2022 Blue of False?

Sally Fairclough, Experienced Zookeeper and Head of the

Black tree monitor (Varanus beccarii)

DID YOU KNOW

all available space. This is not possible for ground-dwelling species. In fact, whilst many people would argue that terrestrial animals are easier to house, this can be another challenge that the keeper must consider. They should not be housed in anything shorter than five feet in length, with six feet being more appropriate. Height is less of an issue, but installing light fixtures may be easier in a taller vivarium and will make room for various hides and artificial or growing plants.

Breeding blue-tongues

There are seven distinct species of blue-tongue skink. Five are endemic to Australia, while two occupy the islands of Wallacea.

In 2020, researchers discovered the most Westernly occurring population of Indonesian blue-tongue skink (Tiliqua gigas gigas) in Sulawesi. It is thought that there is still much to learn about this species and perhaps many more species and subspecies to be described to science.

Blue-tongue skinks

sneeze. In the wild, they will use their noses to push through dirt and sand to search for prey. They use this sneezing to clear out any loose particles that get stuck in their nasal cavities. Keepers should be careful this is not combined with a mucus build-up, which could be a sign of infection.

Blue-tongue skinks are routinely bred by many hobbyists and lots of pet shops will keep a breeding pair as they are usually quite straightforward to breed. However, there are a few notable challenges when embarking on a blue tongue breeding project. Firstly, sexing blue tongue skinks is incredibly difficult. In fact, before the age of around two years old, all species and subspecies are practically impossible to sex without veterinary intervention. Northern blue tongue skinks (T. scincoides) can sometimes be sexed based on their head size and bone structure as they get older. However, the breeder would need to select from a good number of animals to create a ‘best guess’ as a straight comparison between two animals is unlikely to be conclusive. Unfortunately, this method of identification does not work with Indonesian subspecies as both males and females can differ greatly in size and shape.

One method of sexing that applies to all species, including the Indonesian varieties is by identifying the colour of the iris. Males are more likely to have red irises, whereas females are more likely to have yellow irises. This is completely unreliable, as there are many reports of females with red irises and males with yellow. However, it can be used in conjunction with other identifiers to help the breeder make an informed guess.

James Wilson is an expert blue-tongue breeder in the USA. Writing to bluetongueskinks.org he claims: “The presence of, or lack of, seminal plugs has proven to be one of the most reliable indicators that I have used in determining the sex of my blue-tongued skinks. Most hobbyists

overlook this dead giveaway because they keep their skinks on dirt, bark, gravel, or aspen bedding. The seminal plugs simply get lost in the substrate, never to be discovered by the skink's owner. I have found that when I keep my skinks on artificial turf, at least during brumation and the breeding season, the males will "drop" seminal plugs daily. These plugs are small (about the size of a bb) clearish-white slimy little blobs with tails that give them a total length of about 1-inch. They resemble small tadpoles and are usually found in pairs. They are quite obvious on the turf but will dry up by the end of the day, turning a yellowbrown colour and withering into thin brittle twigs. At this point, they are very easy to mistake for a small piece of aspen bedding or a dried up piece of cut grass. Some people confuse seminal plugs with the urates that skinks produce along with their faeces. Urates are the white chalky portion of a skinks waste matter. During brumation, they are produced in the absence of faecal matter, because the skink has not taken in any food, but was still given access to water. This can be misleading, and it is important to know exactly what you are observing. Remember that urates are chalky, and they will crumble up quite easily in your fingers, while seminal plugs come in pairs and look like very small albino tadpoles.”

There are other, more invasive methods of sexing blue tongues. Some breeders will expose their animals’ hemipenes but this can risk damage and future health complications. Finally, an MRI scan will sex a blue-tongue skink with confidence. For breeders dealing with many animals or high-end morphs, this might be a worthwhile investment. For most hobbyists, however, it is a very expensive procedure that is often unviable.

Brumation should be encouraged in Australian species, but it is much less important for Indonesian subspecies. All T. gigas species experience a ‘wet’ and a ‘dry’ season in the wild and therefore do not require a brumation period to breed. This being said, many hobbyists will choose to semi-brumate their animals in anticipation of breeding. Dropping temperatures just a little bit and reducing the photoperiod will mimic wild seasonality. The animals

Title 12 JULY 2022 Blue of False? 12

will lose their appetite and become less active. Keepers of gigas sp. should not drop temperatures below 21°C (as opposed to the Australian subspecies which will happily tolerate 15°C for several months). Not all blue tongue skinks will want to brumate. Even those that experience the harshest conditions in the wild might find that their captive environment does not warrant the need to brumate. Therefore, the keeper should be extra vigilant around winter and observe their animals’ behaviour. If the animal is becoming extremely inactive, brumation is encouraged. If the animal is simply reducing the amount of food they eat during winter, this is perfectly normal and does not necessitate drastic temperature drops.

Once both animals are receptive (females will reportedly react to a little back scratch by raising or wiggling her tail, whilst males are noticeably more active), pairing can commence. The breeding process is anything but romantic. It can be very daunting for a new breeder to watch their animal's mate. Males will be very aggressive and bite the flanks of the female. She will also be pushing back, testing the male’s strength, in what can appear to be a rather vicious struggle. Although males can be introduced to a female’s enclosure, using a separate tub will allow the keeper to observe the process and break up the wrestling if, for example, the male begins biting the females’ feet and toes. Eventually, he will stroke the top of

the female’s tail with his hind legs and, if he is successful, she will lift her tail and allow him to copulate. If they are unsuccessful, they should be separated and paired again a few days later. The female will be receptive for around one month and should not be paired with males more than 3-4 times during this period.

Blue-tongue skinks will generally give birth to between five and 15 young after a gestation period of around 100 days. The young are fully formed, independent lizards that should be introduced to their new enclosures as soon as possible.

The importance of reputable breeders

Anyone who is looking to source an animal should have a keen desire to know where that animal came from. With many shops breeding their own blue-tongue skinks, a few simple questions about the lineage of the animal should help the keeper identify the exact species/locale. Networking with breeders who produce specific varieties is also a great way of picking up unique tips for that locale/subspecies. Hardy species that have occupied herpetoculture for decades often make excellent pets. Sometimes, however, it is the longest-kept species that require the most effort and research to update their husbandry practices.

13 JULY 2022

SPECIES SPOTLIGHT

The wonderful world of exotic animals

Collared lizards (Crotaphytus collaris)

There are currently nine recognised species of ‘collared lizard’ that stretch throughout the arid regions of the Southern United States and Mexico. All species are fast-moving and generally exhibit stunning colouration particularly around the breeding season. Crotaphytus collaris, or the ‘common’ or ‘Eastern’ collared lizard is the most popular species in the hobby and are now routinely captive-bred in the UK.

There are five distinct subspecies of Crotaphytus collaris, all of which present slightly different colouration. Their active personalities, bright colours and reasonably straightforward requirements in captivity makes collared lizards some of the most rewarding reptiles to own and will appeal to anyone looking to keep active desert-dwelling reptiles. It is possible to keep a small colony of one male to two females, but this should be reserved for keepers who have the facilities to separate the animals if the male becomes aggressive (which is common during breeding season). Otherwise, a single male or single female can live happily on their own.

Collared lizards are diurnal and should be provided with Ferguson Zone 3 lighting (UVI range of 1.0 – 2.6, with a maximum of 7.4 in the basking spot). The enclosure should be laid out to ensure that the lizards can move closer, or away from the lighting by providing various décor and hides throughout. Keepers should aim to provide the largest vivarium possible for these active lizards. Although they will not tolerate handling like bearded dragons, a similar set up is recommended. This means a cool end of around 23°C, a warm end of around 30°C a basking spot of 36°C+. Unlike bearded dragons, temperatures should drop quite drastically during the winter months to encourage brumation. Once the lizards wake, they will be more receptive to breeding. Providing a few inches of loose substrate such as Leo Life and Beardie Life is important to encourage natural digging behaviours.

Collared lizards are insectivorous. However, in the wild they will opportunistically feed on brightly coloured flowers found on cacti. As such, a primary diet of crickets, locust, roaches, morioworms and waxworms should make up the bulk of their diet but dandelions, grated carrot and chopped strawberry can also be fed. These are naturally rich in carotenoids but feeder insects should be gut loaded with a premix (or brightly coloured veg) to ensure they are also rich in carotenoids, which helps the lizards achieve their full colour potential.

Species Spotlight

TINC OUTSIDE THE BOX

Dendrobates tinctorius in the wild.

Dyeing poison frog

Like many poison frogs, Dendrobates tinctorius is a highly variable species. Ongoing research in their native range of the Eastern Guiana Shield (Suriname, Guyana, French Guiana and Brazil) has identified a spectrum of over 50 distinct localities, or ‘morphs’. The most popular of which, D. tinctorius azureus was previously thought to be an entirely different species until recently. Colloquially named the ‘dyeing’ poison frog, this species of large-bodied Dendrobate is popular in captivity for its stunning colouration and bold personality. Experts began breeding this species over fifty years ago, but now they are widely available, making it even more important for hobbyists to know exactly where their animals’ roots are.

Nominate (Kaw Mountain)

The term “nominate” basically refers to the “original” (or first discovered) species locality and allows scientists to describe subspecies from a specimen (holotype) discovered in this area. So, for example, if there are several subspecies belonging to the same species, the ‘nominate’ form is the one which was described first and most closely resembles the original description of the species when it was discovered. In this case, D. tinctorius is one species, which has no subspecies. The term ‘nominate’ is therefore incorrect. However, there is a morph sometimes called ‘nominate’ but now more frequently referred to as ‘Kaw Mountain’ which could be described as the original dyeing

poison frog. It is characterised by a black pattern on the dorsal, broken up by a distinct yellow line. The flanks are a textbook yellow-blue and showered in small black dots.

Surprisingly, the ‘nominate’ morph is one of the smallest morphs of the species, with a maximum SVL of just 40mm. They can be found in a remote location in French Guiana, around the Kaw Mountains at low elevations. Naturally, this pocket of rainforest maintains extremely high humidity. They are most closely associated with large boulders and tree trunks and frequently inhabit openings with felled trees.

18 JULY 2022 Tinc Outside the Box

Azureus

Azureus, commonly known as the ‘blue’ poison dart frog was only discovered in 1968 (and officially described the following year) by M.S Hoogmoed. At the time, it was thought to be a new species Dendrobates azureus. This is unsurprising, given that it is the only tinc and possibly the only frog to be a uniform vibrant blue. In fact, it is one of a very tiny number of species that even possesses blue pigment (most use complex light reflections to appear blue). This puzzled Hoogmoed who wrote in his notes: “Among other things, John and Leo reported having seen blue frogs in the forest island. My first reaction was to

ask them how much rum they had drunk that day because nothing like a blue frog existed, and it was like hearing about blue elephants. Anyway, they maintained they had not drunk a single drop of rum, which was indeed most likely, but that they had seen blue frogs hopping about on the forest floor.”

The paper continues: “After about 20 minutes I saw my first blue Dendrobates in the wild. It was sitting on the forest floor on fallen leaves, and when I moved nearer it hopped away with short, quick movements. Its bright blue colour contrasted beautifully with the brown dead leaves.

19 JULY 2022 Tinc Outside the Box

Powder blue

It was easy to capture. During my trip through the creek valley, I saw many more and collected some of them, restraining myself from capturing more than a few because I had no idea about the extent of the forest island and the size of the population of the blue Dendrobates. Also, at the time, I had no idea whether this species would occur in other forest islands in the region or not. Most specimens were on the ground, but a few were moving up the trunks of large trees to… where? During my further stay at Vier Gebroeders Bivouac (till October 7, 1968) I discovered that populations of blue frogs were present in several other forest islands around Vier Gebroeders

Mountain. However, because of the size of the forest islands and the fact that they were not interconnected, the exchange of genetic material between populations was likely to be low, and only some individuals were collected as evidence of their presence in other forest islands. Back in Holland, I set to work on the collected material and, finally, the description of the new Dendrobates, which one year later was published under the name Dendobates azureus (Hoogmoed, 1969). Because of its very striking colour, I could convince the editors of the journal to publish a coloured plate to show the real-life colour. At that time a rare and very costly thing.”

Although azureus is now considered a ‘morph’ of tinctorius, the isolated pockets of jungles have created other colourations. These include paler blue varieties including the ‘sky blue’ and ‘fine spot’.

Citronella

This is the largest of all the tinctorius morphs at a whopping 74mm SVL. They are mostly yellow on their torso and dorsal, with a characteristic black dot on their head (although a small number of animals don’t have the black dot). This morph still has blue legs, most have extremely deep blue (almost black) legs. In 2013

20 JULY 2022

a handful of individuals were imported with pale to bright blue legs. ‘Citronella’ has a wide range in Suriname, but certain populations were reportedly over-collected. Igor Zhidov, an early exporter, claimed he discovered this morph entirely by accident.

Despite female Citronella’s being huge Dendrobates, like the rest of the species, they are highly specialised in small food items. Comparatively, a 74mm member of the Ranidae family would likely feast on large insects and perhaps other frogs. Dendrobates and more specifically tinctorius would happily pick off minute invertebrates such as springtails and aphids. Of course, in captivity, this should be comprised mostly of pinhead crickets, fruit flies and springtails.

Nikita

Nikita occurs in all three countries. It looks very similar to ‘Citronella’ and for a long time was thought to be the same locality. It is much smaller than Citronella, reaching a size of around 55mm SVL and can be extremely variable in its patterning. Some individuals will have lots of black patterns with a spectrum of blues, while others will be almost entirely black and yellow. It is not uncommon for this morph to exhibit bright yellow around their front ankles, which is often a giveaway for identifying them against other locales.

Just to complicate things, not all ‘Nikitas’ will have this bracelet so keepers that have sourced ‘Nikitas’ should seriously consider researching their animals’ history and make notes of the locality they have. Although many novice keepers or first-time pet keepers might not see the importance of genetics, especially if they do not plan to breed their animals, this information may be extremely important. ‘Nikita’ was named after the daughter of one of the exporters in Suriname.

Patricia

The ‘Patricia’ form is found in Suriname and has been bred in captivity in the USA since 1999 and is now often available in the UK. It is characterised by pale blue legs with few spots. The name ‘Patricia’ is thought to have come from expert breeder, Patricia Grueneberg, owner of Vanishing Jewels – an exotic pet shop which pioneered poison frog keeping and has since closed. She was a close friend of the importers who brought the first specimens into the US. At this time, Suriname was rumoured to be closing for export and as more hobbyists turned their attention to amphibians, experts began buying the early imports at extremely high prices.

With the elevated price tag, expert breeders put a lot of time and resources into producing captive-bred animals. Expecting that there would no longer be any wild-caught specimens to mix bloodlines, breeders were extra vigilant with genetics. Now, ‘Patricia’ is one of the most widely available ‘tinc’ morphs. Of course, a wider availability means there is likely some cross-breeding or misidentification now. This morph looks very much like the ‘powder blue’ variety but lacks spots on its legs.

JULY 2022

21

Citronella

Patricia

Nikita

‘Best Aquarium Fish Food’

As voted by readers of Practical Fishkeeping magazine

Aquarium Fish Foods with Insect Meal

Uses cultured insect meal to recreate the natural insect based diet that most fish eat in the wild.

Easily digested and processed by the fish resulting in less waste.

Environmentally friendly and sustainable.

www.fishscience.co.uk

Tumucumaque

The Tumucumaque Mountain National Park is a 38,000mile squared national park in the Brazilian Amazon. It is the world’s largest tropical rainforest national park and is still harbouring many secrets of the natural world. In 2004, a scientific expedition stumbled across the ‘tumucumaque’ morph. The next two years saw 11 independent expeditions aiming to document the little-known species in this region. Several specimens were collected to be maintained in educational facilities. At the time, those individuals were the only legally kept animals.

The ‘tumucumaque’ is possibly the most controversial of all tinctorius morphs. As they live in a protected area, the animals that made their way into the Netherlands between 2006 and 2010 were smuggled illegally. In the US, the offspring of illegally sourced animals are still considered to be ‘illegal’, so these animals were seized and moved into zoos. As the origin of captive-bred individuals became more and more ambiguous, it is thought that the remaining illegally harvested frogs were then sold onto wider breeding collections. Sadly, this is a common occurrence with some species possessing an unscrupulous history. In the case of ‘tumucumaque’ and Adelphobates galactanotus ‘blue’, their introduction to the hobby came at a time when the illegality of these animals was widely documented and shared online. Now, however, they are available in good numbers of captive-bred stock despite very few UK breeders working with them.

It is easy to see why this species is so sought after. This morph is medium-sized and highly variable in its patterning but characterised mostly by a mottled/marble appearance. They can exhibit bright yellows, oranges and even silver elements, often with large black spots. This is why it is sometimes referred to as the ‘peacock’ poison frog.

Robertus

Possibly the most variable of all the commonlybred tinctorius morphs, a single locality can produce a vast array of different animals. Interestingly, the location that

the original ‘robertus’ were first imported from was kept a very close secret for many years and thus, protected wild populations long enough for a good number of captivebred animals to be produced. This locality was discovered by Jan Robertus Hanzen around one decade ago. Initially, it was imported in small numbers to the US and later to Japan. Now it is one of the most popular tinctorius morphs in captivity.

Bakhuis

This is a dwarf variety of tinctorius that is rarely seen in Europe. At just 35mm, they are possibly the smallest variety of tinc. They are found around the Bakhuis mountains in Western Suriname and are predominantly black, with blue and ivory markings. Keepers often say this morph is slightly more cryptic than its larger-bodied cousins. This morph is now being frequently bred in the USA.

The Bakhuis mountains have always been vulnerable to exploitation. Their unique geographical make-up means this region is regularly mined by various companies and de-forestation is a serious concern. In the mid-20th Century the ‘West Suriname Plan’ aimed to mine Bauxite from the region but was later abandoned when Suriname became independent in 1980. As a former Dutch colony, many of the earliest imports of herptiles from the Guiana Shield went directly into Europe through the Netherlands. The ‘Bakuis’ is no exception, as Mr Ensink (Maastricht) and Dr Hoogmoed (discoverer of Azureus) brought the first animals into Europe following their discovery. They bred readily in captivity and are now infrequently seen in captivity.

A ‘northern’ variety of the Bakhuis has also been described. This variety supposedly behaves very differently from other morphs and has been photographed in small colonies. Although tinctorius is known for being aggressive and territorial, male ‘Bakhuis’ have been photographed in groups of five, guarding a communal pool of tadpoles.

JULY 2022 23

Bakhuis

Tumucumaque

Robertus

Tinctorius exports today

Dendrobates tinctorius is a CITES Appendix 2 listed species and has been since 1987. This means that their numbers could become threatened if they are subject to unregulated trade. Therefore, a quota-based system has been implemented which allows a set number of animals to be exported from the wild each year. For example, each year Guyana permits 500 individuals to be exported from the wild. Their data suggests that this is an appropriate number that does not negatively impact wild populations, whilst fulfilling international demand and generating economic value for the peoples who harvest them. Suriname, on the other hand, has historically permitted 1886 animals to be exported each year. Whilst the species is more widespread in this country and most of the popular ‘morphs’ hail from Suriname, this has

been deemed unsustainable by EU officials. Therefore, a suspension was placed on the quota between 2003 –2008. In Brazil, exporting wildlife has been illegal since 1934, but more recently outlined as a ‘crime against the environment’ in 1998. Therefore, any animal or locality endemic to Brazil cannot be exported legally. This has consequently made Brazil the epicentre for illegal wildlife trafficking and ethical hobbyists should be extremely vigilant when sourcing animals from this region.

Now, poison frogs are frequently captive-bred across the world. Amphibians are generally prolific breeders and with specialist equipment more accessible than ever, there is a whole spectrum of species readily available that do not impact wild populations. Contrastingly, extensive logging in the Guiana Shield, including Brazil where it is not

24 JULY 2022

Tinc Outside the Box

considered “a crime against the environment” is perfectly legal. This is proving a significant threat to highly localised populations of D. tinctorius such as “Azureus”, which already live in isolated pockets of forest.

Therefore, it is extremely important that hobbyists only source captive-bred specimens and where possible, continue to breed these animals. It is well documented that D. tinctorius locales will breed with one another, so it is of vital importance that keepers do not house different morphs together. Breeders, who aim to produce more animals in the future should also be extremely vigilant and keep extensive records on the lineage of their animals. Identifying the correct morph can be a good first step, but networking with other breeders and customers to track the roots of the animals, as well as their offspring may help

prevent inbreeding. It is common for siblings to produce viable tadpoles, with young froglets looking very similar to one another it is not easy to identify the offspring of inbred animals. This has already caused many captive-bred frogs to appear much smaller than their wild counterparts. Whilst some argue that ‘fresh bloodlines’ from wild-caught parents are the resolution to this problem, that only helps if the breeders producing the animals are highly selective with their pairings. Animals with poor genetics hold less conservational value as their potential for reintroduction, many generations into the future, is minimal. It would be wrong to vilify the pioneering hobbyists and breeders who provided the eclectic mix of species we see in herpetoculture today, but the more we know about the origins of the animals we keep, the easier it is to make informed ethical decisions.

JULY 2022 25

Tinc Outside the Box

CROSSING THE POND

Zen Habitats launches in the UK

Zen Habitats has gained a huge amount of media attention since its inception in 2017. Now, with the brand growing in popularity and thousands of US hobbyists testifying to the brand’s innovative approach to vivaria, ‘Zen’ is quickly becoming the hot topic in herpetoculture. This year, the brand launched in the UK and Exotics Keeper Magazine caught up with CEO Randy Williams to discuss what this means for keepers on this side of the pond.

Zenspiration

“A few years back my wife and I purchased some bearded dragons” explained Randy. “We noticed some behavioural problems, especially from our male. We bought a ‘bearded dragon kit’ and instantly realised that half the stuff in there needed to be replaced. What I found was an article about how the UK does it. There was really nothing like that here in the US at the time and nothing less than about $800 so I thought “I can make that!”. We went through a few designs, and it turned into a real business interest, not just a hobby. That’s when we started pursuing Zen.”

Zen Habitats has been available in the USA since 2017. During that time, their primary design has been upgraded three times. The UK launch will see two sizes become available in stores later this month. These are the 4 x 2 x 2 and the 4 x 2 x 1.5 feet vivariums in both bamboo laminate and PVC. These enclosures come flat-packed alongside a galvanised steel top, interchangeable grommets, door locks and a substrate shield. Three more enclosure sizes will be available later this year. The new range of enclosures will bring several new features to the UK vivarium market.

Zenovation

One of the most exciting aspects of the Zen Habitats range is the introduction of PVC. Randy explained: “Typical PVC is actually very flexible and with heat and humidity can warp a little. We use composite PVC with more elements that make it much more rigid, like plywood. You can soak it in water for a month and pull it out and it will be exactly the same. It will not get damaged by humidity which is one of the reasons we use it. Our entire enclosure can be fine with 100% humidity and the PVC panels can handle it. What we’ve done to help trap humidity is we’ve provided an acrylic sheet that can be laid on top of the enclosure to stop 75% of the humidity from escaping, whilst also making room for heating and lighting. The enclosures aren’t specifically water-tight but if the keeper uses a ‘bio-basin’ which works like a liner, they can certainly keep that humidity in. In fact, one of the very first things I put in my PVC was some azureus dart frogs. I had three of them in a 4x2x2 and it was great to give them that room.”

Another major breakthrough is coming soon in enclosure design is the ability to connect several vivariums with an extension kit. These are available as frames that can

26

JULY 2022

simply connect two four-foot vivariums to make an eight-foot vivarium, or as a corner unit, which will connect two vivariums together across a corner to create a 10-foot enclosure. With the FBH "minimum enclosure size guidance" being a huge talking point in UK herpetoculture currently, hobbyists will no longer need to throw out their old vivarium to upgrade their enclosure and instead can simply merge two existing vivariums to provide plenty of space for their animals.

“The great thing is that it’s all modular” added Randy. “Our new design in the UK is a flatpack enclosure that you fold open, screw together and you’re ready to go. To extend it, you simply unscrew it, remove one side, and screw them back together.” Although currently, enclosures can only be extended horizontally, Randy told us they could launch a vertical extension kit too.

The introduction of larger store-bought vivaria could have profound impacts on the species we keep and the way we keep them. Randy continued: “Where I’m seeing a difference is in the animals that are already kept. A while ago I put my bearded dragon in a 4-foot-tall enclosure. In Australia, males would go 10, or 20 feet up in the trees to guard their territory. I have tried to emulate this in my enclosure. We’ve also just finished building an enclosure for royal pythons, so mine’s also in a four-foot-tall enclosure. When I first started, people were keeping them in racks. He’s been in his enclosure now for over a month and I’ve never seen him on the ground, despite having a burrow on the ground near his heat source. He’s always on his top two shelves, so we’re aiming to mimic that now with our new enclosures. I don’t think we’ll have bigger animals like monitor lizards, because currently we only have two-foot depth, but we will have more enriching enclosures for the species we already keep.”

As well as extension kits to benefit the animals, Zen Habitats has developed a range of stands and spacers to create a visually appealing display in the home. Not only are they fully stackable, but the use of a ‘spacer’ gives the keeper access to all the electrical equipment above the vivarium via a set of sliding doors. This means that multiple enclosures can be stacked upon one another despite the keeper’s choice of electricals. The

innovation aims to prompt keepers to provide larger enclosures for their animals, whilst still utilising a small amount of floor space within the room.

What’s next?

Although not officially announced on any platforms yet, Zen Habitats is working towards other products to join the market. Randy concluded: “We do have some exciting news actually. The next product we will be launching is an arboreal snake hide. This can also be used on the ground as well. We have team members who are zoologists, vets and animal control etc, so we get a lot of expert input. None of them have found a good arboreal snake hide. So, what this new product is going to do is – it’ll be a fairly big hide that can be attached to our steel screen.

Zen Habitats has already amassed a huge social media following. They have sparked international campaigns to update animal husbandry, particularly in the US and Canada. Currently, they are being used by 15 different zoos, including San Diego Zoo, one of the largest in the Americas. Introducing new brands into the herpetoculture industry often provides healthy competition and accelerates product development. Previously, UVB was thought to be a niche aspect of exotics keeping, reserved only for breeders looking to boost the vitality and egg yield of their animals. Now, almost every lighting brand in the UK provides UVB in at least one of their products. Naturally, this creates competitive price points that make excellent husbandry standards more affordable and more available for new and experienced keepers alike.

27 JULY 2022

An example of Zen Habitats stacked on top of one another

A PVC set up

A bioactive carpet python enclosure

LEGENDS OF THE RAINFOREST

Few snakes are as mysterious and impressive as the bushmaster.

South American bushmaster (Lachesis muta)

South American bushmaster (Lachesis muta)

Comprised of four distinct species from Central and South America, the Lachesis genus, commonly named ‘bushmasters’ are some of the largest venomous snakes on the planet. Lachesis muta or the South American Bushmaster can reach an enormous 11 feet in length, making it the largest viper in the world. Despite this, they are some of the most secretive of all snakes. As in-situ and ex-situ research embellishes our understanding of these mysterious animals, herpetologists are beginning to learn more than ever about these true rainforest legends.

An introduction to bushmasters

Bushmasters are members of the Crotalinae subfamily - a group shared with rattlesnakes, lanceheads and Asian pit vipers. Like their relatives, bushmasters are ambush predators often waiting several weeks coiled in position, waiting to strike their prey with lethal venom. In fact, researchers in Costa Rica discovered one individual resting in the same location every day for two months.

In the wild, bushmasters will typically prey on rodents and marsupials. There are currently no records of bushmasters feeding on amphibians, birds or reptiles although this may occur. Vipers are well-known for feeding on prey much bigger than themselves, but bushmasters, given their enormous size, will feed on relatively small-bodied prey. They will tend to rest under trees with fruiting bodies, to pick off any small mammals that come to feed on the falling fruit. This does place them in immediate danger of their predators, collared peccaries (Dicotyles tajacu). These

small mammals (that look very much like pigs) are known to kill and eat any snake they come across and juvenile bushmasters are no exception.

All bushmasters are considered nocturnal. However, males searching for a mate will become crepuscular as they move around the primary forest in search of a mate. Following pheromones, they are most active around 8 pm and rarely past 11 pm. Being such cryptic animals, little is known about the conservation status of bushmasters. Whilst an individual animal is likely to stay put for several weeks, finding and monitoring the number of new animals is extremely difficult. Even with frequent expeditions and tours to find these animals, few wildlife photographers ever get the chance to see these animals in the wild.

In South America, the Chocoan bushmaster (L. achrochorda) inhabits Southern Panama, stretching

30 JULY 2022 Legends of the Rainforest

across Northern Colombia into the Choco region, as well as Northwestern Ecuador. The South American bushmaster (L. muta) has the largest distribution of all and can be found throughout primary rainforests West of the Andes with the bulk of its range stretching across Northern Brazil. Further North, L. stenophrys (Central American Bushmaster) and L. melanocephola (black-headed bushmaster) can be found throughout Costa Rica, with the former found in the East (and adjacent Panama) and the latter on the West Coast. Researchers are currently pushing to elevate the IUCN Conservation Status of the black-headed bushmaster to

‘Critically Endangered’ as much of its historical range has now been lost to agriculture. Now, this species is only found in the interior depths of the Osa Peninsula. Cesar Barrio Amoros et al write: “Venomous snakes are difficult to protect. Even species known to be rare in the wild or restricted to small ranges are frequently not protected by local, national, or international legislation. Of all Lachesis, only the subspecies L. muta rhombeata is included on the IUCN Red List as Vulnerable. However, that taxon is no longer valid, leaving the isolated Atlantic populations of L. muta totally unprotected in the remaining 7% of the original Atlantic Forest as

of 2008. Lachesis melanocephala, with a total range of 4,828.15 km2, is the bushmaster with the smallest distribution and the most threats to its survival.”

“We further suggest that Lachesis stenophrys, L. achrochorda, and L. muta deserve NT (Near Threatened) status due to their scarcity and a multitude of threats, despite all having extensive ranges. However, conditions within nations vary considerably. For example, while L. acrochorda in the Colombian Choco probably deserves an LC (Least Concern), its dramatically reduced distributions in Ecuador and Panama must be reviewed.”

31 JULY 2022 Legends of the Rainforest

Breeding behaviours

One of the most unique things about bushmasters is their reproductive behaviour. They are the only pit viper in the Americas to lay eggs. Females will coil around their clutch for an incubation period of almost 3 months. From this vulnerable position, she does not feed. Instead, the mother fiercely defends her clutch from would-be predators. Bushmasters are an excellent indicator of a healthy forest. They only occupy the densest inner jungle and therefore, studying the breeding behaviours of this species has been difficult. Historically, in-situ breeding projects led the charge in understanding these secretive snakes. For example, anecdotal observations from facilities in South America have documented that females will lure males in with their sharp, pointed tails. Whether this is a result of pheromones, or a visual cue is yet to be understood.

With in-situ research supporting international breeding projects, bushmasters are now being bred in zoos and our understanding of bushmasters is increasing rapidly. In 2021, ZSL London Zoo was the first UK institution to successfully breed a bushmaster species. Led by Senior Keeper, Daniel Kane, the herpetology department successfully produced five neonate Lachesis stenophrys from an adult pair that they acquired five years prior. Daniel told Exotics Keeper Magazine: “It’s an absolute privilege to work with this species.”

“We put the pair together when they were adults. They had lived separately

for all their juvenile years in an off-show enclosure. We put them into the exhibit in March and had a few months to settle them in. Over the UK winter, it was a bit cooler in the exhibit, especially with the spray system. So, they had gone from large off-show custom exhibits that we manually sprayed, into an on-show exhibit with regular, intense misting. The temperature in the exhibit was also much cooler compared to how it was off-show. I think this was the trigger for them. Cooler and much wetter conditions encourage Lachesis to breed. It’s odd really, with a typical snake you would think a cooler, dryer winter and a hotter, wetter summer would be the natural distinctions between the seasons. It’s the opposite with these guys! They like cold and wet, which is a classic for developing respiratory conditions but L. stenophrys has evolved to deal with that.”

Although the pairing went extremely well, there were some things that the team couldn’t prepare for. Daniel continued: “They were paired in March/ April and by July, at 6 pm as we were walking out the door, we noticed the female halfway through laying a clutch of eggs. It was too late to do anything about it that day. It was just typical that I was going on holiday the next day and I’m thinking ‘why didn’t this happen a day before!’. We didn’t get to see the courtship as I imagine it happened overnight. It would have been amazing to see that. In the future, we will look to get CCTV cameras inside exhibits to record behaviours like that.”

Keepers at ZSL London Zoo were able

to get first-hand experience with the viper’s unusual egg-laying habits. “The eggs are quite large, around 9cm in length which is quite an investment on the female’s part” added Daniel. “The clutch we had represented about 26% of her entire body weight.”

“The rest of the team did a great job of removing the eggs. The females probably would incubate the eggs themselves and guard the clutch against any would-be predators. In the interest of ensuring the eggs come full-term, we intervened, and all five eggs hatched with no issues! Currently, we have three of the five youngsters and the other two have gone to other scientific organisations to help us learn more about the venom.”

Having sourced the bushmaster parents as young juveniles, the keepers had a great understanding of how to maintain the newly hatched juveniles. As a species which is rarely kept, the Zoological Society of London can now accurately study the entire development cycle of the species which has been used to help inform other scientific organisations’ work. One major observation that the team have managed to document is the rate of growth for L. stenophrys. Daniel continued: “We got the original group of youngsters in about six years ago and they grew really quickly! I didn’t know just how quickly they would grow. Within a year they put on around 600-700 grams. We have youngsters upstairs that are about one and a half years old and they’re already 1.2m long.”

32 JULY 2022

Bushmaster husbandry

ZSL have published a ‘best practice’ guide to help inform other organisations on successful husbandry methods. Drawing on research from in-situ studies and supported by the teams’ personal experiences visiting Central America, they have developed a finely tuned exhibit to maintain the animals. Daniel continued: “Many of the books say this species only survives in primary rainforest and that certainly seems to ring true. We have created an exhibit with lots of holes and hiding spaces. They don’t seem to tolerate warm temperatures. Obviously, in Central America we expect it to be warm for a lot of the year. These guys do spend a lot of their time in burrows of armadillos or agoutis which helps moderate the temperatures, keeping them cool and humid. Without that fauna, you lose the structure of the habitat the bushmasters are reliant upon. In secondary forests, you have more Fer-de-lance (Bothrops asper) which can withstand the higher temperatures and live more readily around humans.”

Naturally, creating an enclosure designed for a highly specialised species requires a significant amount of research and planning. In the wild, reptile distribution can be dependent on elevations, microclimates, specific flora and fauna and just about any other variable within an ecosystem. Sometimes these elements can be contradictory and recreating this with limited resources can be a challenge. “We have learnt they need a humid but dry environment” explained Daniel. “That’s extremely difficult as the two do not go hand in hand. Obviously to raise humidity you would usually turn on the misting system and saturate the substrate. But if bushmasters don’t have somewhere dry to rest, over some time you can get a reddening of the ventral scales which is quite well known in Lachesis. To combat this, we’ve got a nice deep layer of leaf litter which will dry out quite quickly. As well as a deep layer of substrate to hold onto the humidity, plus misting systems that go off twice a day. We’ve cracked it now, but that did take a little while to get right.”

Being the world’s oldest scientific zoo, ZSL London Zoo has a whole wealth of resources to ensure the species is kept at optimal conditions. Despite being a potentially very dangerous animal to manage and one which reaches an immense size, the keepers at London Zoo are fully equipped to facilitate appropriate husbandry. “We have two snakes living in the exhibit which is about four meters

across and two and a half deep” added Daniel. “It also sits on a hillside, so when it’s quite warm they have the choice of temperature gradient and hiding opportunities. We have humidifiers across the exhibit too, so it’s entirely on them whether they want to be warm, cool, dry or humid.”

“Maintaining a good environment for this species does take a bit of work. They do best kept at around 20-25°C. We have air conditioning, so we can raise and lower the temperature. We also have that off-show, which can be set to a gradual increase. Instead of it hitting 9 AM and bumping straight up to 25C, it’s a slow process that mirrors how it would be in the wild. They have basking lights as well. I’ve read in the past that they don’t require this and that’s not how they thermoregulate. We have a large enough space here to provide them with the option to, which I think is really important.”

In rare cases, when the animals need to be moved or have medical check-ups the team at ZSL use a ‘hands-off’ approach. By using two sets of professional snake hooks, they can keep a lot of distance between the keeper and the animal. The size of the exhibits is also a key component of safety. The keepers can physically enter the exhibit after containing the snakes to undertake any maintenance work. Daniel continued: “When it comes to measuring environmental parameters and changing lightbulbs or measuring UV index etc we must take the animal out of the exhibit. We remove them and place them into a box which we either leave inside the exhibit or take outside

“I think it’s very important that we have a bigger purpose for keeping animals in zoos. In the time that we have maintained the species here we’ve written a paper on how we’ve kept and bred bushmasters and another paper on a novel method of sexing the species. We believe this could apply to other species of viper too. This information can gradually help to improve our understanding and welfare of the snakes we care for, and ultimately this is knowledge we can share with scientists and conservationists across the world.”

33 JULY 2022 Legends of the Rainforest

– Daniel Kane, Senior Keeper ZSL

Hatchling Central American bushmaster (Lachesis stenophrys) taken by Daniel Kane / ZSL London Zoo

Daniel Kane / ZSL London Zoo

DID YOU KNOW

Legends of the Rainforest`

of the exhibit. They’re an absolute dream to work with so it’s mostly very straightforward. We also use specialist equipment. For example, your typical snake hook is just one curved piece of metal. With a large heavy-bodied terrestrial snake if you’re only picking them up with one or even two thin hooks it’s putting an awful lot of pressure on particular points on that snake. So, we use very wide hooks to help spread that weight more evenly and make it more comfortable for the snake. Should we need veterinary intervention we also have clear tubes that we can encourage them into to get a closer look.”

has had far-reaching implications for medical developments. Keepers that work in an official setting such as zoos or laboratories can contribute venom samples to schools of tropical medicine across the world. In some regions, this is more prominent. For example, Australia Reptile Park has had a snake venom programme since the 1950s and a spider venom programme since 1981. They have been the sole providers of terrestrial snake venom in the country and have since saved an estimated 20,000 lives. The more recent ‘spider venom programme’ sees them house over 2,000 funnel-web spiders to create important new medicines.

The name Lachesis references the second of the three Greek fates. In Greek mythology, Lachesis decided how much time a person has. This is a clear nod to the potentially lethal bite of the Bushmaster.

The South American bushmaster is the longest pit viper and the second-longest venomous snake in the world, beaten only by the King Cobra ( Ophiophagus hannah ).

Bushmasters are dedicated parents and will coil around their clutch of eggs to protect them from would-be predators. The incubation period can last up to three months. During this time, the mother never leaves the clutch’s side.

“They’re extremely calm natured. We have other species of viper that are more prone to show defensive behaviours when disturbed. Bushmasters, in my experience, tend to sit still and are obliging to work with. This can be disconcerting sometimes as, when they’re fed, they can be accurate with their strike.”

Working with venomous snakes

In the UK, a DWA (Dangerous Wild Animals) licence is required to keep front-fanged venomous snakes. However, local councils can also impose extra restrictions on zoos. For example, City of Westminster Council demands that the site also keeps antivenom available for the kept species. For certain genera such as Crotalus, this very expensive product expires quickly and must be replaced frequently. This has created challenges for even the largest zoos, including ZSL London Zoo. Daniel continued “we now focus our work primarily on EDGE species. These are animals that are “evolutionarily distinct and globally endangered”, and means we can prioritise our conservation efforts to focus on the most unique species on the planet. Although Western diamondback rattlesnakes (Crotalus atrox) are incredibly impressive animals, we had to invest a lot of money in their upkeep and so it made sense for us to exhibit a species which would benefit more from a conservation perspective instead.”

Although DWA-keeping in the private sector is an incredibly niche field, the development of husbandry practices as well as safe-handling methods

Here in the UK, captive-bred venomous snakes can help support international programmes. Collaborative research is helping to save countless lives across the world, especially in lessdeveloped countries. The World Health Organisation estimates that between 81,000 and 137,000 people are killed each year due to snake bites. In Australia, where several of the most venomous species live, just three people are killed by snakes each year (this number is similar in the USA despite several highly dangerous rattlesnake species being present). Therefore, international efforts to produce antivenoms that are accessible globally is extremely important.

In the Central American bushmasters’ native range of Costa Rica, huge strides are being taken to reduce snakebite fatalities. As a country which is perhaps more financially stable than most Central and South American countries, snakebites still pose a threat to both people and animals. At a 2016 WHO conference, Costa Rican officials outlined a plan to cut snakebite mortality rates in half by 2030. With international institutions learning more about the venom of the most dangerous snake species, this goal is much more achievable.

Daniel concluded: “Of the five juveniles that we had, two of them have gone to an organisation in the UK that works primarily with venomous snakes. It’s great that these animals can go on to help others learn more about Lachesis. Perhaps we’ll learn more about the venom which could have any number of pharmaceutical applications in the future.”

JULY 2022

34

SHOCKING DISCOVERIES FOR LIMB RE-GROWTH

New scientific developments have found that human limb-regeneration treatments may be closer than we think.

35 JULY 2022

Regeneration is a widely documented phenomenon, but one which is restricted to just a few species of animals. From deer that can re-grow antler skin, bones and nerves to axolotls that can re-grow organs and flatworms that can re-build their entire selves, the concept of ‘regeneration’ has been tantalising scientists for centuries. Not only do these species provide invaluable insight into biology itself, but the practical applications for a medicine designed to prompt limb regrowth are immense. Now, scientists are starting to discover that these obscure capabilities might not be limited to individual species. With the correct medication and a better understanding of bioelectricity, perhaps we could encourage limb re-growth in more species, including Homo sapiens.

The Levin Lab