Giovanni Segantini’s frames

by The Frame Blog

Giovanni Segantini (1858-99), Spring in the Alps, 1897, o/c with fragments of gold leaf, (45 11/16 x 89 3/8 ins (116 x 227 cm.), in its original artist’s frame, Getty Center, Los Angeles

In January 2019 the Getty Museum announced that it had acquired Giovanni Segantini’s large and impressive mountain landscape, Spring in the Alps (1897), painted en plein air in the mountains where he spent much of his working life. This announcement came with the publication on the Museum’s website of a short but informative essay on Segantini’s career and on the painting, which included this sentence:

‘In excellent condition, Spring in the Alps comes to the Getty in the elaborate frame that the artist originally designed for it.’ [1]

Segantini, Spring in the Alps, reframed by the Museum in 2022

Three years later, however, in April this year, the LACMA blog posted a piece on the reframing of this painting:

‘Frames, it’s said, are not to be noticed. They can however shift the perception of a painting, and that’s clearly the intention with the Getty Museum’s new frame for Giovanni Segantini’s Spring in the Alps. The former ornate gilt frame has been replaced by a white Shaker-esque design that emphasizes the artist’s modernism. Segantini is little-known to American audiences, and his Alpine subject matter can be misread as chocolate box conservative’ [2]

This seems an astonishing misdirection of the spectator away from the artist’s work and intentions. Collectors in the past have often reframed the pieces they have bought or inherited as a way of imprinting their ownership on them, or marrying them with other works in their galleries, or as part of the redecoration and updating of an interior which has descended from an older generation [3], but a better, less subjective and more historically enlightened approach must be expected today of the world’s major museums. Since the German curator, Wilhelm von Bode, began in the 1880s to campaign for a museum in Berlin which would display paintings, sculpture and decorative art from the same period all together, in one integrated interior, the path to museum presentation should surely have been heading progressively in this direction, with artists’ frames in particular retained, conserved and captioned.

It is also a reversal of the way in which Impressionist paintings are presented, usually in décapé 17th-18th century Baroque French frames chosen to blend these avant-garde works into the homes of their first owners (often with revival Baroque interiors), and sometimes in 19th century gilt Salon patterns.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), La Brouette dans un verger, 1879, o/c, 53.5 x 64.5 cm., Musée d’Orsay; in its current 19th century NeoClassical revival fluted gilt frame

Pissarro, La Brouette dans un verger, 1879, montaged into the type of frame in which it might first have been exhibited in 1880 (here, a Degas frame has been used, in default of other survivals) [4]

When they achieved wider recognition and sufficient wealth the Impressionists may themselves have returned to the use of giltwood or gilded plaster frames, but their early work was exhibited in simple white or coloured mouldings: and who would now dare to reframe those paintings in reconstructions of such settings, however suitable, and however much based on historical accounts?

How foolishly daring, then, to use this kind of pseudo-‘modern’ frame on a work which it does not suit, and which would never have been displayed in such a way (the brilliant white border interfering markedly with the tonal harmony of the painting). And ‘Shaker-esque’? Shakers were warned that ‘no paintings shall ever be hung up in your dwelling rooms’ [5], rather negating the concept of Shaker frames. This is a description of the new frame from the website of another museum, to be sure, but it’s a strange term to pick for a pattern which – in order to have any credibility at all – it must have been hoped would be associated with the frames of European Post-Impressionists and Symbolists, and which has been applied to a painting by an artist with a Catholic background, whose work is stuffed with Catholic symbolism. It is expressive of the extraordinarily confused reasoning which has both instigated and flows from such a misguided action – and, since Segantini, his paintings and his frames can hardly help being contemporary with each other, how does encasing this picture in a spurious frame ‘emphasize his modernism’?

Segantini’s early frames

Segantini (1858-99), Ave Maria on the lake, second version, painted in 1886, of original (destroyed) 1882 work, o/c, 120 x 90 cm., Segantini Museum, St Moritz

Segantini had a relatively short life with a deprived and impoverished childhood, raising himself from an illiterate life on the streets of Milan to a position in the late 19th century as one of the most popular and important contemporary artists in his own country, and as a well-known name in many others. His training seems to have consisted of five years (four of them in evening classes, and one as a fully enrolled student [6]) at the Accademia di Brera in Milan, yet by 1883 he had been awarded a gold medal at the World’s Fair in Amsterdam for the first version of the painting above, Ave Maria on the lake.

Segantini (1858-99), The cabinetmaker Mentasti, 1880-82, o/c, 109 x 73 cm., framed in 19th century revival style, possibly under Mentasti’s aegis; private collection

One of Segantini’s fellow students at the Accademia di Brera was the slightly older Carlo Bugatti (1856-1940), who went on to work for a Milanese cabinetmaker called Mentasti, subject of the portrait above. Mentasti owned a workshop, the Piccolo Stabilimento di Lavorazione del Legno, and Bugatti seems to have passed on some of the decorative painted work which it generated to Segantini, who had become a close friend; he also became Segantini’s brother-in-law when the latter married Luigia Bugatti (‘Bice’) in 1880. The portrait of Mentasti was (according to one theory) painted by Segantini as a gift for Bice, and may have been framed in the workshop. This early contact with the design and production of furniture and decorative art may also have sharpened Segantini’s evident interest in the frames of his paintings, helped by the acknowledgement in the late 19th century art world of the importance of the frame generally to the work of art.

Carlo Bugatti (1856-1940), set of bedroom furniture for Luigia Bugatti & Giovanni Segantini, c.1880 [7]; in the sepia photograph the bed is undecorated but may be another version. Signed dressing-table, c.1880, various woods, pewter, copper, bone, 103 x 93 x 53 cm., Wright Auctions, 15 December 2011, Lot 362

Bugatti’s imaginative and innovative designs for his own workshop – with their idiosyncratic asymmetry, eclectic influences from Moorish, African and Japanese furniture and ornament, and use of all kinds of inlay – included looking-glass frames and screens with shaped panels; these may well have influenced some of Segantini’s more adventurous frame designs of the 1890s. The set of bedroom furniture made for Segantini and his wife by Bugatti in 1880 or later was painted with naturalistic flowers by the artist himself, in the same intimate involvement with his friend’s work as with Bugatti’s productions for Mentasti; the dressing table is inlaid on the top with Segantini’s name in pewter (circled). Furthermore, elements of the design of the bed and table can be seen in the elaborate drawings which Segantini made for the framing of his great Triptych of Nature, or Panorama of the Engadine, at the end of his life (see below).

Segantini (1858-99), Donna bionda, or Portrait of the artist’s wife, Bice, 1878-79, o/panel, 31 x 28.5 cm., Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan. Photo: Sailko

His earlier pictures are framed in a more conventional style: that is to say, they use traditional architectural and organic ornaments, and profiles which might be found in many of the European Salons of the 19th century. However, the decorative mouldings don’t pretend to be replicas of Renaissance or Baroque models, but are, rather, based on them; they are carved in the slightly chunky manner which is peculiarly 19th century, and are assembled with the profiles which they enrich in a slightly off-beat way. For example, in this portrait of his wife from the later 1870s, a year or two before their marriage, a reverse architrave profile combines a Mannerist undercut or bird’s beak gadrooned moulding with a rope ornament at the sight edge in a rather unusual positioning. Perhaps Segantini may even have carved it himself?

Segantini (1858-99), Portrait of the art dealer Vittorio Grubicy de Dragon, 1887, Museum of Fine Arts, Leipzig. Photo: Sailko

After his painting The choir of Sant-Antonio was acquired by the Società per le Belle Arti di Milan in 1879, Segantini was taken up as the protégé of the critic and artist, Vittorio Grubicy de Dragon, who ran a gallery with his brother Alberto. Both Grubicy brothers successively became his patrons, agents and friends, as well as his dealers, and Vittorio is supposed to have introduced him to the divisionist technique. With this support, Segantini may have been better able to afford the carved giltwood frames which came to characterize his method of presenting his work; he may also have been able to have them carved to his own design at a discounted price, either in Mentasti’s workshop (if it was still functioning in the 1890s), or in Bugatti’s (Bugatti set up on his own in 1888). The portrait of Vittorio Grubicy has a Baroque revival leaf frame, which may have been rather the choice of the sitter than the artist. It is a traditional pattern which was reproduced fairly frequently in 19th century Italy, but is a splendidly apt setting for the Bohemian artist and gallery owner.

Segantini (1858-99), La mia famiglia, 1881-82, o/c, 65 x 49.5 cm., Private collection

Segantini (1858-99), Still life with fish, 1886, o/c, 54 x 109 cm., Segantini Museum, St Moritz

Segantini (1858-99), Still life with mushrooms, 1880s, Segantini Museum, St Moritz

Some of Segantini’s other works of the 1880s, including at least two still life paintings and one of his wife, his eldest son, and the nursemaid, Baba, La mia famiglia, are also framed in revival patterns. These, however, are more unusual: weighty torus frames decorated with elaborate garlands of fruit, which are based on the Renaissance garland frames used in the 16th century for circular images of the Madonna and Child. In this respect, the frame of La mia famiglia is analogously appropriate, whilst the frames of the still life paintings are still life compositions themselves. They may have been suggested by Grubicy as a method of subliminal suggestion to potential buyers that these contemporary paintings are in fact old masters in the making, clad in the garb of Titian, Botticini and the Della Robbia; and they are also not too dissimilar from the genre of the Salon frame. On the other hand, the pairing of opulently sculptured 16th century-style festoons of fruit with painted boxes of sardines, lettuce leaves and heaps of dead fish, or mushrooms wrapped in newspaper, may be an ironic comment on the distance between a modest rural diet and the gilded lives of art collectors.

Segantini’s frames and social comment

Segantini (1858-99), The pumpkin harvest, 1897, o/c, 83.8 x 145.1 cm., and detail, Minneapolis Institute of Arts

Much later, in 1897, Segantini or his dealer chose an elaborated version of the same garland frame for the Hardyesque anti-pastoral, The pumpkin harvest, in which the coming of the railways shatters the comparative quietness and hard, unchanging labour of workers in the fields. Perhaps here the style of frame is intended to contrast with the threat which industrialization brings, or perhaps it has a more optimistic note, a nod towards Turner’s image of such progress subsumed by the forces of nature in Rain, steam and speed.

Certainly, by around 1890 Segantini, like many of his peers, was drawn to a socialist vision for Italy in the face of economic crisis and political disaffection, and his great divisionist paintings are not merely ‘dry landscapes… and brooding pastorals’ [8], but works which combine an edenic vision of life in vast panoramic mountainscapes with an unsparing depiction of the relentlessness of agricultural toil there. From this point of view, the extraordinarily ornate and flamboyant gilded frames provide an essential commentary on the subjects they contain; they elevate peasant workers to the status of wealthy professionals – military, clerical and academic sitters – and simultaneously use the juxtaposition of frame and painting as a sardonic note on the difference of those various lives.

Segantini (1858-99), Potato harvest, 1886, o/c, 115 x 220 cm., and detail, Private collection

The frame of The potato harvest is especially pointed in this respect – a wide, sculptural, undercut spiral of scrolling acanthus leaves wrapped around a knobbly branch which is breaking into bud, which may symbolize the old order of aristocratic classicism smothering the primitive, youthful strength of the workers. It is exaggerated in scale in order that the viewer doesn’t miss the subtext, and deliberately (it seems) distinguished in its use of fine detail and traditional motifs in contrast to the Millet-like treatment of the workers. Segantini had been introduced to Millet’s work by Grubicy [9]: also to the work of the Hague and Barbizon schools, and their influence clearly underlies his paintings of agricultural labour in the stony soil beneath the Alps.

Segantini (1858-99), Ploughing, 1890, o/c, 116 x 227 cm., Neue Pinakothek, Munich

Millet (1814-75), Gleaners, exhibited 1857 Salon, o/c, 83.5 x 110 cm., Musée d’Orsay. Photo: fmpgoh

Segantini, Ploughing, detail of frame left, and Millet, Gleaners, detail right

The frame of Ploughing is in a more conventional Salon frame in Louis XIV revival-style, which is similar, fortuitously or not, to the frame of Millet’s Gleaners, exhibited in the Paris Salon more than thirty years earlier. Segantini’s painting may appear at first glance more sunnily ‘modern’ in comparison to Millet’s, but both works are plainly linked in their subject-matter and in the political comment implicit in them, and this link is underscored by the similarity here of the frames. It would be a myopic and dim person who put Millet’s Gleaners into a stark white architrave frame with the intention of ‘emphasizing the artist’s modernism’ [10].

Segantini (1858-99), Pascoli alpini (Alpine pastures), 1895, o/c, 169 x 278 cm., and detail, Kunsthaus Zurich

Gradually, the mountainous landscapes which Segantini lived amongst became the vehicle for a philosophic consideration of life, and for its spiritual expression. Here, in a scene which is almost Biblical in its subject and setting, the evocation of a timeless rural way of life may conjure links with more metaphorical Shepherds, but also describes the connection of the land and those who live on it in terms of a classical Arcadia. The frame of this landscape, massive and weighty in proportion to a canvas more than nine feet wide, has a sculptural spiral rope moulding around its contour – or perhaps an elongated barley-sugar column from a Gothic altarpiece – and a frieze decorated with centred and tied branches of oak leaves and acorns. Oak is traditionally a symbol of strength and endurance, sacred to Zeus, and grows on the lower slopes of the Alps.

Symbolist frames

Segantini (1858-99), The punishment of Lust, 1891, o/c, 99 x 172.8 cm., Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

Segantini used flowers as well as specific leaves to impart further meaning to a painting through their incorporation into its frame. The punishment of Lust, which was bought by the Walker Art Gallery two years after it was painted, has a frame which is superficially another version of a Salon frame from the 1850s to 1880s (for example, see Richebourg’s photos of the 1861 Paris Salon , and Cabaillot-Lassalle’s painting of the 1874 Salon).

Segantini, The punishment of Lust, corner detail of frame with images of the Alpine trumpet gentian (gentiana dinarica). Photos of flowers: H. Zell

However, the half-flowers carved along the top edge are quite specific in their depiction, and seem closest in likeness to the Alpine Trumpet gentian, which would be appropriate to Segantini’s home in the Alps between Liechtenstein and Milan, or to the Alpine Pasque flower, a variety of anemone. Both of these have appropriately symbolic meanings: for the gentian one of its meanings is justice, which applies neatly to the subject of the painting: the punishment of ‘wanton’ women, who have been condemned to float on the winds of an icy mountain landscape, rather like the adulterers in Dante’s Inferno, who are blown around their circle of hell on a perpetual storm of lust [11]. The Pasque flower is also appropriate, since another name for the wild anemone is ‘windflower’: it heralds the spring winds, opening only when the wind blows upon it, and it also gives protection against evil. This is one of Segantini’s first large-scale Symbolist paintings on the theme of morally-compromised women and bad mothers [12], and the frame was evidently an important element of the whole work. The stars on the hollow of the frame are probably the attribute of the Virgin, the counterbalancing good mother.

Segantini (1858-99), Le cattive madri (The bad mothers), 1894, o/c, 105 x 200 cm., Upper Belvedere, Vienna

The bad mothers is another stage, as it were, in this particular theme: where the women in The punishment of Lust are condemned for their pursuit of empty pleasure at the expense of motherhood, those who do bear children, like the woman in the foreground, are rescued from the everlasting winds by the branches of the Tree of Life. However, although this later painting may be seen as a pendant to the first, and both have been referred to as a diptych, they are slightly different sizes and have very different frames. The frame of The bad mothers seems to be entirely without symbolic reference to the painting; however, its ornament can be seen instead as an expansion on the idea of redemption in the painting, so that the Tree of Life, depicted as bare and lifeless, becomes a flourishing leafy garland around the contour of the frame.

Segantini (1858-99), The bad mothers and The punishment of Lust, both 1896-97, o/cardboard, 40 x 74 cm., Kunsthaus, Zurich

The small versions of both paintings in the Kunsthalle, Zurich, are framed alike, but in a pattern which has little to do with Segantini’s normal elaborately ornamental style. However, it is effectively a modernization or remaking of a classical fluted frame, with the flutes following the length of the rail (rather than crossing it) in a simplification of a pilaster.

Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916), Peasant working, 1908-10, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna, Rome

This fluted pattern is associated with paintings made more than a decade before Umberto Boccioni was to use the same architectural motif for his own frames – probably having borrowed it directly from Segantini (see also his Officine a Porta Romana, and Campagna con alberi e ruscello).

Segantini (1858-99), Il dolore confortado dalla fede, 1896, o/c, lunette: 84.5 x 132 cm., main image: 151 x 131 cm., Hamburger Kunsthalle, acqu. from the artist, 1898

Segantini used the same fluted moulding to frame his vertical diptych, Il dolore confortado dalla fede or Grief comforted by Faith, in another pioneering update: this time, of the two-tier Renaissance altarpiece. This pared-down version of a classical aedicular frame seems, from the viewpoint of the present day, to be in proto-art deco style, but is, rather, an extremely innovative and radical advance on contemporary Symbolist frames. His attitude to Symbolism generally is summed up in a sentence reported by Emilio Gavirati:

‘I will paint pictures with an international character, pictures in which the English will recognize Burne-Jones, and the French, Millet; I will introduce into my paintings a touch of that symbolism from the North’ [13].

Giorgione (1477-1510) or Titian (1488-90-1576) Christ carrying the Cross, c.1505, o/c, 68.2 x 88.3 cm., and (workshop of Titian) God the Father, Scuola Grande di San Rocca, Venice. Photo: Sailko

Perhaps he had been looking at works such as the Giorgione/ Titian altarpiece, Christ carrying the Cross, with its Titian workshop lunette of God the Father, which had been famous for centuries for its miracle-working powers as much as for its authors. It is notable that Segantini’s diptych depicts a wordless exchange of two figures in the presence of death, with a lunette showing the soul in heaven borne by angels – as it might be, a recasting of the San Rocca altarpiece, with Christ on the verge of death and His executioner in the lower tier, and God the Father surrounded by angels carrying the instruments of Christ’s Passion above. The frame of this 16th century diptych is a Venetian aedicule with turned and fluted baluster columns, cherubs’ heads, foliage and flowers. Segantini’s austere fluted structure, with a vestigial cornice, has only stylized flowers to soften it, and sun-rays in the spandrels of the lunette.

With subjects like these, diverging in various degrees from his more realist works, Segantini seems to have felt an even greater impulse to experiment with the form and ornament of the frame.

Segantini (1858-99), Pagan goddess, or The goddess of love, 1894, o/c, 210 x 133 cm., Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan

His Aphrodite, floating in a De Morgan-ish, sub-G.F. Wattsian way diagonally across the canvas, seems not to have been felt or animated in the way that his human women and mothers invariably are, but the frame, like the single coffer of a painted ceiling, gives a gravitas and presence to an unusually weak painting which rescues it from itself. This frame, with its garland of bunched flowers in the frieze and its pairs of large and small spandrel arabesques, is a unique reimagining of a 19th century revival pattern which gives the whole work the appearance of having been levered out of the interior of some palazzo.

Segantini (1858-99), The angel of Life, 1894, o/c, traces of gold powder, 276 x 217 cm., Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan

The angel of Life, of which there are four versions, is the complete opposite of The goddess of Love (although, strangely, the latter and the large Angel in Milan were commissioned as a pair by a banker, Leopoldo Albini). Unlike the remote and disengaged Goddess, the Angels are studies in a tenderness with which the artist empathized, the Madonna figure being based on the family nursemaid and model, and the child on Segantini’s son. They are also the final step in redemption from Le cattive madri. Seen together, it is possible that the floating personification of erotic love is (like the bad mothers) also intended to evoke the figure of Francesca from Dante’s Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, punished for adultery by being perpetually blown about on the winds of their passion, whilst the Angel is a figure like the poet’s Beatrice, the personification of spiritual love, whose historical counterpart, Beatrice Portinari, shared a nickname, ‘Bice’, with Segantini’s wife.

The frame of the Milan Angel must have been designed to contrast with the frame of the Goddess; it is also shaped, but its upright axis and simplicity, its polished wooden contour and modest ornament, are as removed from the frame of the Goddess as the colouring of one painting differs from that of the other. The opulence of the Goddess frame is lavishly prodigal in its classical (pagan) decoration, whereas the smaller and more delicate spandrels of the Angel (also symmetrical on both axes) are centred with roses, emblematic of the Virgin.

Segantini (1858-99), The angel of Life, 1894-95, oil, watercolour, gold & silver powder/paper, 59.5 x 48 cm., Szépmuvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

The frame of the small Angel in Budapest is different again. This painting stands alone, with no pendant, and the frame refers to its own world. It is a trompe l’oeil shaped and pierced setting, imitating Celtic ornament with interwoven twig- and withy-like panels over the frieze, which are held between larger, branchlike mouldings; all of it referring to the dead branches in the painting, which the Madonna will stir into new life.

Segantini was very interested in the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, their ‘second wave’ of followers, and probably many of the British artists in the last quarter of the 19th century who experimented with realistically coloured and lighted landscape painting, Symbolism, and frames. However, in the latter case, it is uncertain how much he would have been able to discover about their designs, since frames were even then excised from illustrations of the paintings, and Segantini was limited by his passportless condition as to where he could travel to international exhibitions. There were examples of Celtic motifs used on frames, in the work of Frank Dicksee and the jointly-painted Druids…, by George Henry and Edward Hornel; there were also the wild, twiggy frames, like birds’ nests (gilded with great difficulty, one would think, and a lot of cursing by the framemaker), made for John Anster Fitzgerald’s fairy paintings; but could Segantini have seen or even been aware of these? Perhaps the nature of the frame of the Budapest Angel is a natural extension of his use of symbolically leafless branches, and the dense weaving of the twigs signifies that their barrenness has been controlled and made into something useful through the power of motherly tenderness.

The Triptych of Nature

Segantini (1858-99), sketch of exhibition rotonda to hold the Panorama of the Engadine for Paris EXPO 1900, 1897, charcoal, black crayon, Conté crayon/cardboard, 52.7 x 53.2 cm., Segantini Museum, St Moritz

What became the artist’s final project, left unfinished at his death from peritonitis in 1899, was intended to be the focus of a whole pavilion at the 1900 Paris Expo Universelle, where it would, in theory, have circled the walls inside the building – half beehive, half domed chapel – designed for it by Segantini. It was to be a huge and continuous panorama of the Alpine landscape in the Engadine valley, 20 x 220 metres, in which his intention was to

‘…create the perfect illusion that the observer is high in the mountains, in a green meadow, surrounded by jagged peaks and sparkling glaciers…’ [14]

This illusion was to be carried on by an internal rocky ‘set’ full of real pine trees, Alpine plants, cows and running water.

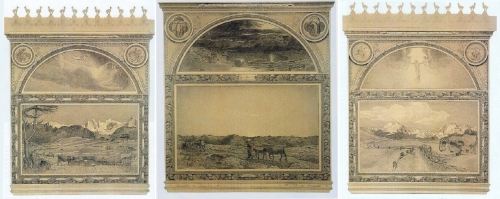

Segantini (1858-99), drawings for Il Trittico della natura (The triptych of Nature); La vita (Life), La natura (Nature), La morte (Death), 1898-1899, pencil on paper, Segantini Museum, St Moritz

In the end, however, such a vast tableau, along with recreated mountain air and realistic lighting, proved to be far too expensive for the pavilion’s sponsors, and over the next two years the idea was whittled down to the more affordable Triptych of Nature. Even so, this would have been a massive work, since each framed panel was originally to have been twice, or almost twice in the case of the centre, as large as each of the three surviving paintings.

Segantini, pencil study with frame for (1) La vita (Life/ Becoming; left-hand panel of the Triptych of Nature), Segantini Museum, St Moritz

Segantini, pencil study with frame for (2) La natura (Nature/Being; central panel of triptych), Segantini Museum

Segantini, pencil study with frame for (3) La morte (Death/ Decay; right-hand panel of triptych), Segantini Museum

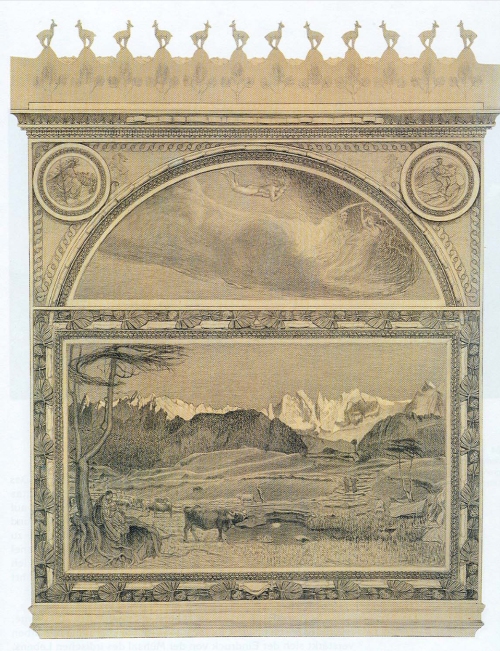

Those three paintings from the projected lower tier, apart from the preparatory designs (above) and drawings for parts of the upper tier, are all that remain of the whole work, although they also have the inner frames which Segantini intended for them, and which are faithful to the pencil studies. The original altarpiece-like conception for each panel is an elaboration of the arrangement used in Il dolore confortato dalla fede (1896), above, with its oblong lower painting and lunette: for the Triptych, roundels have been inserted in the spandrels, the paintings outlined in architectural mouldings, a classicizing pedestal and cornice added at top and bottom, and a cut-out frieze mounted on the cornice of the two side panels. The latter would have been decorated (possibly painted?) with a foliate design which runs faintly beneath the silhouettes of chamois standing on stylized mountains. In the central panel, the roundels have inset quatrefoil paintings. The finish is completely speculative, although the remaining inner frames have been gilded overall.

Segantini (1858-99), Triptych of Nature displayed in the Cupola Hall of the Segantini Museum in the present day

The Triptych on display in the Museum in an undated photo, showing more of the original frames

The Segantini Museum, its eye-catching cupola hall based on the rotonda intended for the Paris Expo, was built in 1908, nine years after the artist’s death, and three years later the three paintings of the Triptych had been secured as the centrepiece of the project. They have been displayed there ever since – although, mysteriously, with less today of their surviving frames than they have had in the past. The lower photo of the two above reveals that the cornices shown in the pencil studies for the three works (above the upper tiers, and below the silhouette crests on the two side panels) were previously mounted on the tops of the three existing frames, and their shaped pedestals were still in place at the bottom. This is confirmed by a black-&-white photo, presumably taken earlier than the coloured one, which shows two of the panels, with Death rather strangely hanging on the left of Nature instead of to the right. At that point they were hung significantly higher, above a panelled dado (although it is quite hard to see how the dado, pedestals and cornices could all have been accommodated in the same vertical space). The cornices and pedestals no longer appear to be held in the Museum [15].

Segantini, La vita (Life/ Becoming), 1897-99, o/c, 192.5 x 322 cm., Segantini Museum. Photo: Gottfried Keller Foundation

Segantini, La natura (Nature/Being), 1897-99, o/c, 236 x 402.5 cm., Segantini Museum. Photo: Gottfried Keller Foundation

Segantini, La morte (Death/ Decay), 1897-99, o/c, 191.5 x 323 cm., Segantini Museum. Photo: Gottfried Keller Foundation

Segantini, detail of the frame of Nature, the frieze decorated with pine fans, cones and birds

The surviving frames of the three paintings are extremely faithful to their appearance as the inner frames of the altarpiece-like structures shown in the pencil studies. They have architrave profiles, with an additional deep chamfer at the sight edge beneath a complex fluted leaf-like ornament, leaving the whole area of the frieze (also chamfered back towards the wall) to be filled with an extraordinary three-dimensional carved garland of pine fans, pine cones, and little birds which are feeding on the pine kernels.

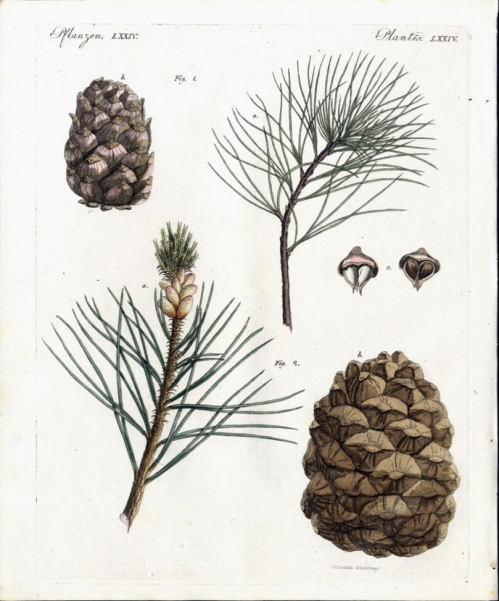

Friedrich Bertuch, Nadelhölzer mit essbaren Früchten (Conifers with edible fruits), 1798, plate 74, showing the Swiss stone pine or Arolla pine (Pinus cembra)

The shapes of both the pine fans and their cones are botanically-accurate depictions of the Arolla or Swiss stone pine, which is indigenous to the Alps where Segantini was working. They continue the painted theme of the Engadine landscape across the frames, as well as adding a metaphorical reflection of the cycle of life. The birds are almost certainly red crossbills, whose beaks are specially adapted to extracting the kernels from pine cones by jamming the scales open, or (less likely, because of the beak shape) woodpeckers. It would be extremely interesting to know who the carver was, who was responsible for turning Segantini’s drawings into such faithful realizations in gilded wood; also, of course, whether there is an even deeper connection to the Engadine, in the wood used to make the frames.

It is easy to see, contemplating the accuracy of the design and carving and the care with which the frames were made, that the complete tiered altarpiece-like structures would – if they had ever been finished – have produced an extraordinarily impressive and grandiose effect, as well as some enormous bills. How much more powerful, breath-taking and expensive Segantini’s pavilion at the 1900 Paris Expo would have been, with 4,400 square metres of painted panorama (presumably framed around the top and bottom of the canvas circle), and the internal reconstruction of a micro Engadine landscape…

Spring in the Alps

Segantini (1858-99), Spring in the Alps, 1897, o/c and fragments of gold leaf, (45 11/16 x 89 3/8 ins (116 x 227 cm.), in its original artist’s frame, Getty Center, Los Angeles

Bearing this immense, clipped-wing work of talent and imagination in mind, it is possible to look with new eyes at Spring in the Alps, painted simultaneously with the beginnings of the three Triptych panels, in 1897, and deframed with such little ceremony by the Getty in May 2022. Although not as large as those, it has a related viewpoint and composition, dealing similarly with the cycle of nature and work in the Engadine, and with the connection of all forms of life to the seasons there; so it might be expected that Segantini would have used the frame in the same way, to bind the setting of the painting to its contents and to make another natural reference explicit.

Segantini, Spring in the Alps, detail of artist’s frame, with narcissi from the southern Swiss alps

Unlike the Triptych frames, this one appears at first glance to be another Salon frame, following Millet’s use of the style for his own paintings of peasants, their life and labour; however – looking more closely – the sprigs of flowers between the S-curves of acanthus leaves are not, in this case, stylized and non-specific florets but actually tiny groups of Alpine narcissi, which fill the meadows of the region in late spring. Just as there are no Arolla pines in the Triptych paintings, so there are no narcissi in Spring in the Alps; Segantini is referring outwards on the frames of his works to other aspects of his local region, and to plants which are emblematic of the nature which surrounded him.

The frame of this painting is referred to in his letters, and even makes an appearance as a sketch in one of them. In January 1897 Segantini writes to Alberto Grubicy, telling him that,

‘The frame [for Spring in the Alps, or Primavera in montagna] will be fine if made after the model you have, and the width of 26 cm. will work well; the sight size of the frame remains an unalterable 230 x 120 cm. Please therefore order it straightaway, to be made well and within a reasonable period.’[16]

Shortly before, however, he had painted a portrait for the Ospedale Maggiore in Milan, showing the father of one of their benefactors, which, with pictures of other members of the same family, was to join the large collection of historic portraits in the hospital’s gallery. Segantini was, by the 1890s, the best-known and most popular contemporary painter in his country, and his work was in demand for exhibitions with other groups of artists across Europe. He was endeavouring to give his paintings the widest possible exposure, and he wanted to show the hospital’s Portrait of Carlo Rotta in the 1897 International Exhibition in Venice (Spring in the Alps had at that point been destined for the 7th Secession Exhibition in Munich [17]). The hospital expected it to be delivered to them in February so that it could be shown in the biennial exhibition of their collection of portraits in March, but Segantini couldn’t enter a work which had already been publicly exhibited in Milan into the Venice exhibition, and was therefore going to pretend innocent confusion over the delivery date of Carlo Rotta to the hospital in order to get his way [18].

Collection of portraits displayed in the arcade of the Ospedale Maggiore in 1920, IRCCS Ca ‘Granda Foundation Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan

Segantini (1858-99), Portrait of Carlo Rotta, post-1897, tempera & o/c, 121 x 201 cm., IRCCS Ca ‘Granda Foundation Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan

Apart from this avoidance of the hospital’s own exhibition (in the end he was forced to get their permission to send the painting to the International Exhibition in Venice, and later to one in Vienna) [19], another problem was that the same black gallery frame was ordered for every portrait in the collection, and the frame for Carlo Rotta was currently residing with them in Milan, awaiting the painting.

Segantini told Grubicy that ‘…of course we must make or adapt a frame…’ [20]. He had wangled an extension of time from the secretary of the Venice exhibition which would have allowed him to complete and enter Spring in the Alps there, rather than in Munich (the painting had been delayed due to bad weather), but for some reason then changed his mind again. He asked Grubicy to have a new frame made for Spring in the Alps in the interval before submissions were due for Munich, whilst the frame already completed for it was to be adapted for the Carlo Rotta portrait and the exhibition in Venice.

Segantini, sketch for converting the frame of Spring in the Alps for the Portrait of Carlo Rotta

He sent a sketch with his letter of 7th March, showing how this was to be done: the short side of both works was 120 cm., and the long side of the landscape was 30 cm. greater than that of the portrait. The gap would therefore be filled with a gilded inlay, and

‘…the cartouche in question can be inscribed, in Gothic lettering, Ritratto del benefatore dell’ospedale maggiore di Milano Carlo Rotta [‘Portrait of the benefactor of the Ospedale Maggiore in Milan, Carlo Rotta’]’ [21]

The Salon-like profile and decoration was perfectly appropriate as a temporary exhibition frame for the portrait, and the motif of Alpine narcissi could be thought of as referring to the legacy of Carlo Rotta’s son, Giuseppe (which had been left to the hospital with the provision that he, his wife and his father should all have their portraits painted for the collection): it might be taken to symbolize both the general area, and ideas of regeneration and growth. It is not clear what happened to this frame, however, since when the hospital eventually received the portrait in August 1897, six months later than they had expected, it was put into their uniform black frame. Presumably Segantini kept the giltwood frame, and used it for another landscape.

During late March and April, he nagged Grubicy about having the second frame ready for Spring in the Alps; he sent him a postcard on 2nd May, having at last brought the painting almost to finishing point:

‘Here it always rains and I am only in need of the frame for the picture with its glass’ [22],

and another on 22nd May:

‘Today it rains heavily but I still hope to be in Milan on Monday we will show the painting to friends and leave quickly to be in time for Munich’ [23].

Jacob Stern’s house in San Francisco, on the corner of Washington and Maple Street, built in 1910

Spring in the Alps had been commissioned by the American collector, Jacob Stern (1851-1927), so its public appearance in Europe was officially limited to its entry in the Secession exhibition in Munich. Segantini took it back to finish (which he was still doing in November 1897), and it then departed for Milan in January 1898, on the way to its destination in San Francisco; although the artist told Grubicy:

‘Yesterday the painting “La Primavera” left here. I accompanied it to the border, and it will reach you at very quickly. I recommend that you exhibit it, in the last room in the usual place, at an angle, like this. Tell me if you like it. Have it photographed’ [24].

Stern was the son of one of the two founders of the jeans-making company Levi Strauss (named after his uncle); he was made its president in 1890, and and ran it with his brothers from 1902 [25]. After his death, Spring in the Alps went on long-term loan to the Legion of Honor/ FAMSF, remaining there from 1928 until it was sold in 1999 to French & Co of New York; in 2015 it was advertized for sale at $40 million.

Although it has remained in California, the state of the client who commissioned it, it is a disgrace that its present owner (an otherwise reputable museum) should be so careless of its overall history and context as to remove what should be an inseparable element of the gesamtkunstwerk – the overall work of art, designed by the artist and decorated with motifs which expand upon the content of the painting. Shame upon the Getty…

****************************************

With very grateful thanks to Marc O. Manser, for his generous help, time and trouble over Segantini’s letters; to Dottore Mirella Carbone, Director of the Segantini Museum (who emphasizes that, ‘For Segantini, frames were an integral part of his works); and to Dottore Paolo Galimberti, Director of the art collection of the Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan

****************************************

Davide Gasparotto, Senior Curator of Paintings at the Getty (but nothing to do with the frame removal), talks about Spring in the Alps in this video:

https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?ref=watch_permalink&v=652636608503644

[1] ‘19th century landscape by Giovanni Segantini joins the Getty collections’, 14 January 2019

[2] ‘Segantini reframed’, 14 April, 2022

[3] A random example of the reframing of inherited works is given by Poussin’s Adoration of the Golden Calf and its associated paintings, for which see a brief summary in ‘Serge Roche: Cadres français et étrangers du XVe siècle au XVIIIe siècle – Part 2’

[4] See also ‘How Pre-Raphaelite frames influenced Degas and the Impressionists’, where La Brouette dans un verger is shown in ‘a rose-coloured setting’

[5] Daniel Patterson, ‘Shaker gift paintings’

[6] Treccani Biographical dictionary of Italians, vol. 91, 2018

[7] The colour photo first published by Amanda Dunsmore & John Payne, Bugatti: Carlo, Rembrandt, Ettore, Jean, exh. cat., 2009, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

[8] Jonathan Jones, ‘Radical light’, The Guardian, Wednesday 18 June 2008

[9] Treccani Biographical dictionary, op. cit.

[10] ‘Segantini reframed’, op. cit.

[11] Dante’s Inferno and Paradiso had been influenced by The vision, a story by a Benedictine monk, Alberico of Settefrati (b. c.1100), based on his own dream as a 10 year-old child of visiting Heaven and Hell. In the late 19th century Luigi Illica, librettist to Puccini amongst others and also a friend of Segantini, wrote a poem, ‘Nirvana’, which was also influenced by Alberico’s work, and this fed into Segantini’s paintings

[12] Segantini’s mother suffered from depression due to the loss of his elder brother in a fire, and was unable to care for him or to feed him properly. She died when he was seven, and his father sent him to live with his half-sister in Milan. A year later his father died too, and his sister was forced to support them by going out to clean, leaving the young Segantini locked in their rooms. He had no education, and was at least partly illiterate into his teens

[13] See Giuliana Pieri, The influence of Pre-Raphaelitism on fin de siècle Italy: Art, beauty and culture, Modern Humanities Research Association, 2007, p. 118, which notes that Gavirati’s quotation of Segantini’s words was first published in ‘an article… in Marinetti’s journal Anthologie-Revue…’: ‘…comporrò dei dipinti di carattere internazionale, dipinti in cui gli inglesi riconoscano Burne-Jones ed i francesi Millet; introdurrò nelle mie composizioni un tocco di questo simbolismo che viene dal Nord’

[14] Segantini, quoted by Andrew Ray in ‘A panorama of the Engadine’, 17 July 2016

[15] Information from Dr Mirella Carbone, Artistic Director of the Segantini Museum

[16] Annie-Paul Quinsac (ed.), Segantini: 30 years of a European artist’s life in unpublished letters between the artist and his dealers, 1985, letter 567, January 1897

[17] Ibid., letter 580, March 1897, note 1

[18] Ibid., letter 576, 25 February 1897, note 2

[19] See the entry for the Portrait of Carlo Rotta in Lombardy Cultural Heritage

[20] Ibid., letter 576, and note 3

[21] Ibid., letter of 7th March 1897, and notes

[22] Ibid., card of 2nd May 1897

[23] Ibid., card of 22nd May 1897

[24] Ibid., card of 25th January 1898

[25] See ‘David Stern: Partner in Levi Strauss & Co.’, Jewish Museum of the American West; ‘Levi Strauss and his family’

Enjoy reading you blog so much! I just discovered it an hour ago! As an artist I early learned that buying expensive frames for my work was a total waste of money, since the client would remove it and put something that fit their the pillows in the sofa or fit the other furniture in their living room. It hurts all the way into the marrow to see how Getty vandalized the perfectly matched looks of Segantini’s works by believing that they had to modernize the frame! Not only does it misfit time vice ,but it also changes the color harmony by overdoing the amount of white. And thereby Segantini’s painting looses the fine light that he created. Now the green grass can no longer enlighten the snow and gets dull. They forget that the color of the chosen frame make certain colors in the painting glow! A good artists is always aware of how big a color area can be without destroying or killing the harmony and light in a picture . But an insensitive buyer can destroy it in a second. Thank you again! I will promote your blog!

LikeLike

Thank you – how kind of you! – and I apologize for such a belated reply.

LikeLike

Thank you, Lynn, for this great article. It is so imperative to highlight the ignorance of the meaning of the original frame for an interpretation of the work of art still existing, if not even spreading more these years, in the important public institutions, despite of decades of research and evidence that a frame on the painting, particularly from the past centuries, deserves a careful consideration and if it is original it should be preserved united with its painting. I admire your great work, Lynn.

LikeLike

Thank you in return, Margaret, for such a kind compliment and just comment. Over the past few decades, the Australian museums have done a great deal to preserve, research, and if necessary replicate original frames, in an exactly opposite move from this inexplicable and wrong-footed action of the Getty, and I wish that more institutions in Europe and the US would follow them. Please keep going!

LikeLike

I would like to see what the Getty has to say after reading this enlightening article!! As for Shaker-esque, as you point out, what an infelicitous term to be used in reference to a frame, especially an art institution…

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comment. I’m afraid that the Getty seems to be staying very quiet, so perhaps they feel unable to defend the indefensible. I should point out that the blog which I took to be the public voice of LACMA seems to be a private one, so the use of ‘Shaker’ as a description of the new Ikea-ish frame isn’t actually the museum’s own; however, the fact that the look of the frame could even spark such a comparison says an awful lot about its unsuitability for the Segantini.

LikeLike