A Century of Chess: José Raúl Capablanca (from 1910-19)

Hi!

I have exciting news to share. I've been working with GM Cyrus Lakdawala and FM Carsten Hansen on a book based on A Century of Chess. The book covers chess from 1900-1909 and is a great way to have the series (plus Cyrus' annotations!) in one place. I'll be sharing more about it in the next weeks. Many thanks to all the readers here for making this possible!

Best,

Sam

JOSÉ RAÚL CAPABLANCA

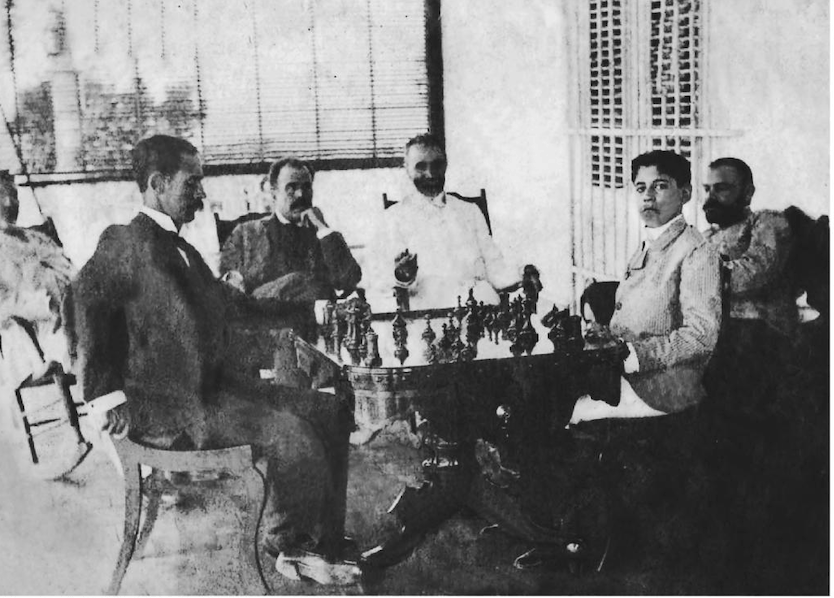

For a long time, Capablanca was a sort of hidden legend. There was the story of how he had started to play — somehow figuring out the rules of chess all on his own and, when he was four years old, correcting a wrong move in a game his father was playing. And there was his achievement winning the championship of Cuba when he was 12.

But, for an extended stretch from 1901 to 1909, Capablanca apparently played very little and had a ‘normal adolescence,’ matriculating as an engineering student at Columbia and playing on the freshman baseball team. There’s some confusion about how much he really studied as a child. Capablanca liked to give the impression — and this has been the general assumption about him — that he had been fully formed as a genius and was able to reach a world class level without any preparation. "I attribute my precocious start in chess partly to a mastery of the principles of the game, born of what I often felt to be a peculiar intuition, and partly to the possession of an abnormally developed memory," Capablanca wrote. But there are some hints that he studied extensively as a child ("it had become a passion," he conceded), and then, once he had thoroughly absorbed the game, never really needed to work again at it. I get the sense that Chess Fundamentals mirrors a program of study that Capablanca (or Capablanca’s father) put him through as a kid — and with the program being notable for its simplicity. The idea, first of all, was to ‘play backwards’ — start with the winning endgame and then figure out a system of simplification in order to reach it. Capablanca seems to have almost entirely dispensed with opening theory but developed an approach where he developed rapidly and unobtrusively and then, based on the targets afforded to him by an opponent’s position, embarked on a forceful middlegame plan, which, surprisingly often, led with no real drama to rapid simplification and the won endgame.

Capablanca had appeared in enough exhibition and simultaneous games to establish his reputation, and, in 1909, Frank Marshall agreed to play a match against him. Capablanca wrote, with his usual matter-of-fact immodesty, "I can safely say that no other player ever performed such a feat as it was my first encounter against a master, and such a master, one of the first ten in the whole world." Playing over the games of the match, Marshall‘s agony is readily apparent. It’s a bit like watching Kasparov against Deep Blue or Lee Sedol against AlphaGo. Marshall was a really great, endlessly creative player, but, against the 20-year-old Capablanca, he seemed to be confronting a higher order of chess. Capablanca pulled ahead seven games to one and was playing pellucid, mistake-free chess. Marshall improved as the match went on, to some extent learning to play Capablanca — he drew nine games in a row to staunch the bleeding — but by that point it was too late.

More wonders were to come. Marshall’s recommendation secured Capablanca a place in the San Sebastián 1911 super-tournament, and there — against the very best in the world — Capablanca won by a half point. It was the most impressive début since Paul Morphy in 1858. As Lasker wrote, "This is a great moment in his life. HIs name is known everywhere, his fame as a chess master is firmly established. And he is 22 years of age. Happy Capablanca!"

From that point on, it was completely clear that Capablanca was speaking special and the world championship a forgone conclusion. In a world tour in 1913-14, he scored +19-2 against masters and +718-96 in simultaneous exhibitions. The enchanted feeling passed into his personal life as well. He had dropped out of Columbia, but the Cuban government appointed him to the highly nebulous position of vice consul with the presumption that he would be a full-time chess professional (his first diplomatic responsibility, for instance, was the tournament at St Petersburg 1914).

For the first 16 rounds of that tournament, Capablanca gave a master class. Sergei Prokofiev, who had forgotten all about music to serve as a chess journalist at the tournament, described him as "an utterly irresistible person, lively, handsome, quick-witted and — this is the point — a genius." And then, abruptly, his tournament position collapsed. In the finals Lasker outfoxed him in one of the most famous games ever played and then in the next round Capablanca committed one of the only tactical oversights of his career to lose against Tarrasch. He recovered, winning his last two games, but Lasker managed to stay ahead of him to win the tournament.

Nonetheless, Capablanca had reached a golden period of his career. After the Tarrasch game, he went thirty games without a defeat. He lost a game to Oscar Chajes in 1916 and then went ninety games and eight years until his next loss. At New York 1915 he went +12-0=2. At New York 1916, against a tougher field, it was +12-1=4. At New York 1918, against a highly credible field, it was +9-0=3. Organizers had the bright idea of arranging a match with Borislav Kostić — who had finished an undefeated second at both New York 1916 and 1918 and had a safe positional style that might match up well with Capablanca’s; Kostić abandoned the match after Capablanca had won the first five games. Capablanca returned to Europe in 1919 to play at Hastings and there scored +10-0=1.

Apart from the one blot of the Lasker loss, Capablanca’s record during this run was one of the single most extraordinary feats in chess history — and Capablanca would make good on that defeat by whitewashing Lasker +4-0=10 in their 1921 world championship match. For much of the chess world, Capablanca wasn’t even so much a rival as a player apart — he clearly had been born to play chess; he played with an accuracy that no one else could even approach (“you make no mistakes,” a stunned Lasker had said to him); and he became the first chess figure to really have a reputation outside of chess, to, as Prokofiev had observed, serve as a sort of living personification of genius.

Capablanca's Style

1.Concrete plans. Again and again in Capablanca’s games, I emphasize his ability to find, at the earliest possible juncture, a concrete strategic plan that drives the rest of the game. Fischer, who was being critical of Capablanca, wrote that “he played with such brilliance in the middlegame that the game was decided — even though his opponent didn't always know it — before they reached an ending.” But that could be extended further. Often it seemed like Capablanca was envisioning the endgame pretty much from the opening — spotting the permanent features of the position and then gradually isolating them. This was never as pronounced as in the following game against Winter, which, essentially, was won by move 10.

2.Short lines. Capablanca was able to steer his way through the middlegame through the highly-accurate calculation of short lines — a trait that he shared with Karpov. I’m not sure that this is a skill that can be particularly learned — all chessplayers endeavor to calculate short lines with accuracy — but it’s worth noting how far that trait took Capablanca. One quality that gave him was a magical ability to withstand the most devastating attacks — and, especially early in his career, to claw his way out of horrible-looking positions. In spite of his reputation as a positional player, he wasn’t making assessments here based on general considerations — he had his innate ability to rapidly and accurately calculate variations and was able, very often, to survive right on the edge of the precipice.

3.Simple Positions. It’s unclear to me exactly how Capablanca managed to so consistently outplay his opponents in ‘simple positions.’ Part of it, I think, was a psychological block that other players succumbed to but that Capablanca didn’t experience: their brains went to sleep in positions lacking the opportunity for direct attacks on the king and they tended to drift towards passivity while Capablanca appreciated the importance of coming up with concrete plans and for acquiring advantages, however minute.

Capablanca in the Opening

Simply put, Capablanca skipped over the opening entirely. The lines he chose — the Four Knights, quiet variations in the Ruy Lopez, Old Indian setups — were completely benign. But — largely because he allowed himself to fall into constricted positions as black — he did work out some of the crucial hypermodern and ‘Hedgehog’ ideas i.e. the ability to create a spiky, flexible position and then to lash out at the moment an opponent overextended.

Sources: Capablanca's Chess Fundamentals and especially My Chess Career are key sources on him. Miquel Sánchez's José Raúl Capablanca: A Chess Biography is the key secondary source. Edward Winter posts a series of articles on Capablanca.