PMA Highlights: Hopper's Pemaquid Light

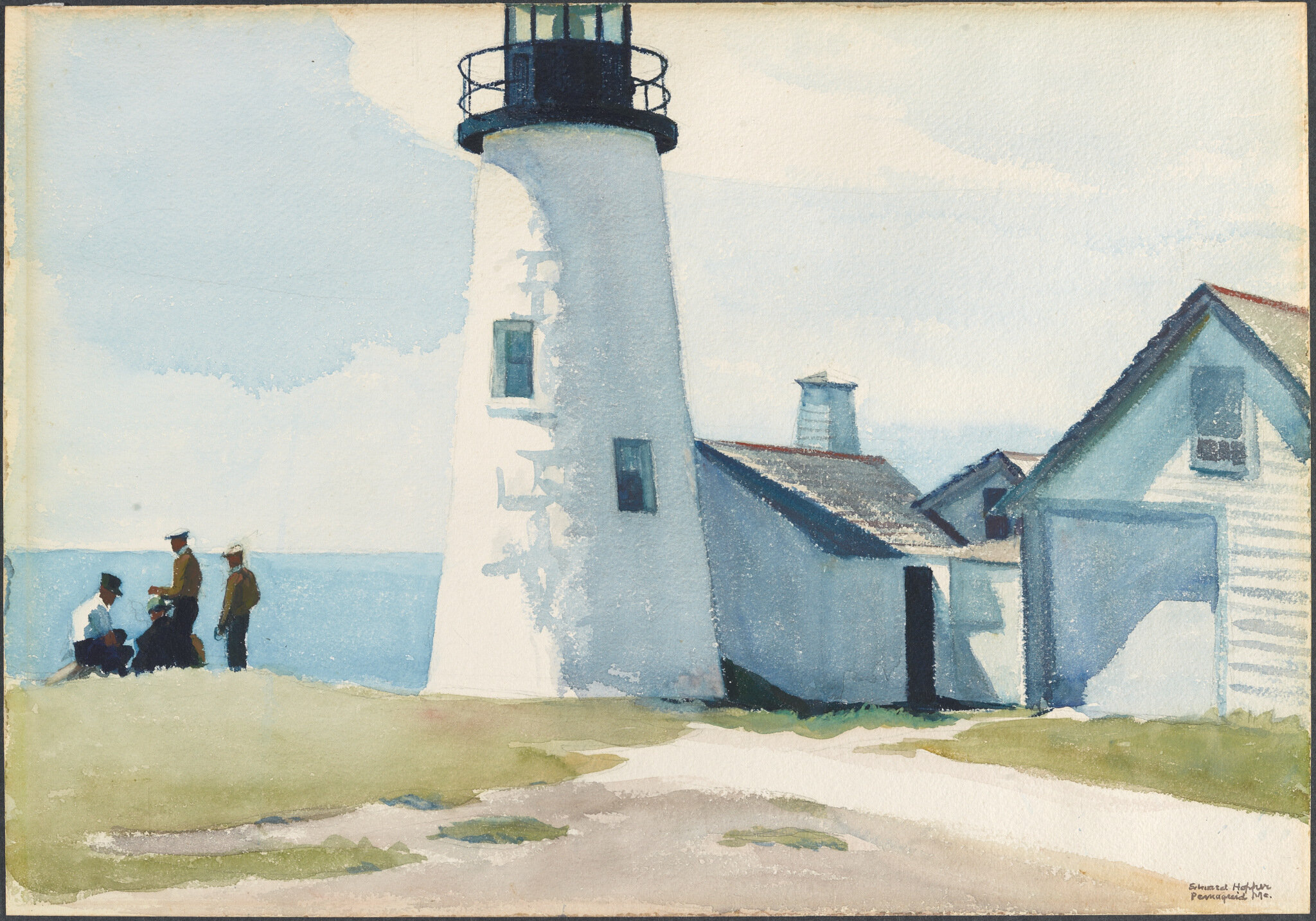

Edward Hopper (United States, 1882 - 1967), Pemaquid Light, 1929, watercolor and graphite on paper, 14 x 20 inches. Anonymous gift, 1980.166

By Karen A. Sherry

This article is featured in The Collection: Highlights from the Portland Museum of Art

The 1920s marked an important transitional moment in the career of realist painter Edward Hopper.

After early struggles, he started to earn critical acclaim for his paintings, allowing him to give up the commercial illustration and etching work that had previously sustained him. Hopper also began a more serious engagement with watercolor, establishing his lifelong practice of working in watercolor outdoors during summer sojourns in New England and in oil in his New York studio during the winter months. Between 1926 and 1929, the artist spent several summers in Maine visiting Rockland, Portland, Cape Elizabeth, and Pemaquid, where this watercolor was made. (After 1929, he summered in Cape Cod, Massachusetts.) In Maine, his favorite subjects included some of the state’s most iconic structures: the lighthouses that dot its rugged shorelines. Jo (Josephine) Nivison Hopper described her husband’s lighthouse pictures as “self-portraits,” suggesting an analogy between such structures and Hopper, who was also tall, solitary, and taciturn. Pemaquid Light depicts the nineteenth-century lighthouse and its ancillary buildings, located at Pemaquid Point on the Muscongus Bay in the Midcoast region. The Hoppers stopped at this site between June 27 and July 3, 1929, while wending their way up the coast from their base at Cape Elizabeth, south of Portland.

Pemaquid Light showcases the austere stillness, clarity of forms, strong lighting effects, and unusual perspective that are hallmarks of Hopper’s mature oeuvre. The top of the lighthouse is cropped off and the structure is seen from the back, rather than from a more picturesque vantage point showing it perched high on a surf-battered headland. Always a deliberative artist, Hopper first laid down a light pencil sketch to establish the outlines of the buildings. Broad washes of transparent colors—mostly blues and purples—depict the expansive sky, band of sea, and long shadows on the structures, with green and brown hues for the grassy foreground. He used more controlled strokes for architectural details and the area along the curved face of the lighthouse where sunlight turns into shade. This passage provides a sense of movement in an otherwise static composition, as these expressive strokes suggest the flickering effects of light reflecting off waves. Hopper masterfully exploited the transparency of the medium to allow the bright white of the paper to show through the watercolor, imbuing the scene with the crystalline brilliance of a sunny New England day. Interestingly, Pemaquid Light is the only one of his lighthouse pictures to include figures—a notable exception, given Hopper’s renown for capturing the sense of alienation and loneliness associated with modern life in America.