How ‘Alien’ creature designer’s works are star of 2 Swiss medieval towns that offer an unlikely mix of idyllic backdrops and morbid art

- H R Giger was born in the Swiss city of Chur, where his style of blending human physiques and machines developed, possibly influenced by his surroundings

- Museums, houses and bars here and in Gruyères tell the artist’s story and exhibit unusual works that put him on Alien director Ridley Scott’s radar

Chur, capital of the eastern Swiss canton of Graubünden, is the oldest city in Switzerland, its well-preserved medieval centre a warren of pastel-painted mansions sitting on the right bank of a still-infant Rhine.

Conservative, and nearly 50 per cent Catholic, this charming city was reluctant to recognise its most famous son – the painter, sculptor and designer H R Giger, whose fantastical and often morbidly sexualised work was considered to be charmless and likely to give religious authorities the vapours.

Before Alien, the artist was already known for posters and for album covers such as prog-rock supergroup Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s Brain Salad Surgery (1973).

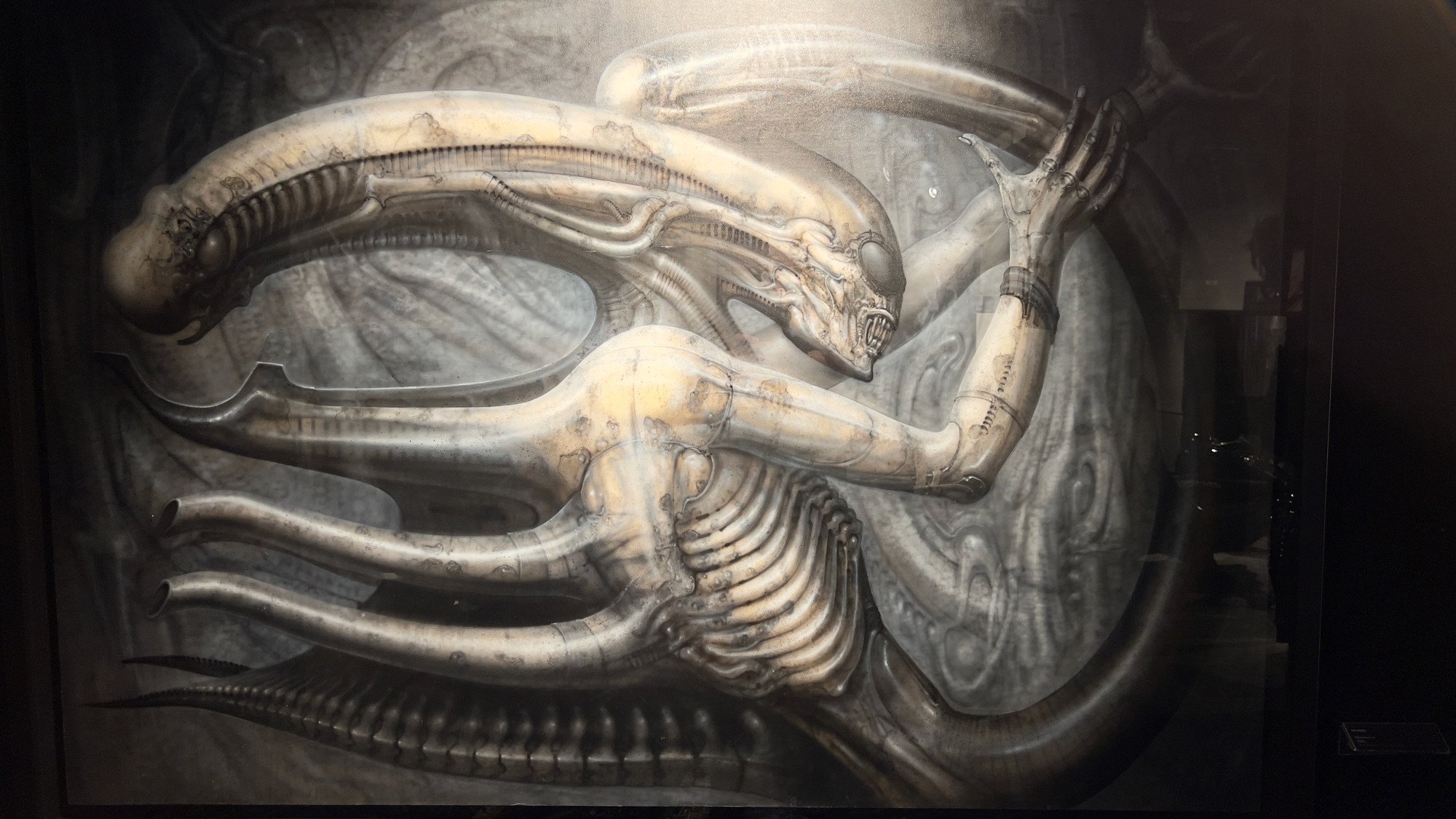

Necronomicon, a book of his art published in 1977, garnered a cult following with its airbrushed images of part-organic and part-machine creatures called biomechanoids. Scott decided he wanted one of its creatures in 3D.

And it was the Oscar-winning success of Alien that finally forced Chur to pay attention to Giger.

Even so, it was not until 2007 that the city’s Bündner Kunstmuseum art museum staged a major solo exhibition of Giger’s work, a relic of which - the shiny silvery torso of a semi-mechanical female creature with spikes for nipples, Torso with Long Skull Shape - still stands in its grounds.

The museum displays the work of many world-famous artists with local connections, including painter and sculptor members of the Giacometti family, and the Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner.

But after the Giger exhibition closed, Torso was removed to storage and only returned after public protests, and those mainly from tour guides who knew what visitors wanted to see even if Chur itself was still in two minds.

Hans Ruedi Giger was born in 1940 in Rabengasse, an alley in the city, although his first five years were spent hidden away at a mountain chalet, unlit at night and perhaps an early influence on his dark imagination.

The Giger family’s four-story house in Chur still stands, and its lemon-painted facade has a cheerful look, although the father’s ground-floor pharmacy, now a cosmetics shop, was also said to have had a certain darkness.

The shop counter bore a skull of which the younger Giger was terrified. Determined to overcome this fear, the boy put it on a leash and would lead it down the street like a dog, perhaps as far as what is now named Gigerplatz.

It’s an equivocal honour, the small square not having previously been thought significant enough to have a name. But in a nod to the gloom of Giger’s art, the sign is in black rather than the blue of other street names. The square’s drinking fountain of 1722, one of more than 150 around the city, now has the bottom of its basin tiled with Giger designs.

The young Giger was also terrified of an ancient Egyptian mummy still in the town’s Natural History Museum, and visited it repeatedly until this fear was also overcome. Skulls and Egyptian themes appear frequently in his work.

Chur’s substantial Catholic cathedral, built between the 12th and 13th centuries and which Giger attended as a boy, is a winding walk uphill through the old town.

Perhaps the child shook off boredom during tedious sermons by contemplating a sinister gargoyle-like figure of a human torso - its boniness characteristic of his own later art - held between the paws of a giant lion, which featured in the cathedral.

The solid town hall displays three of Giger’s more restrained images, inspired by New York, but his most public presence is a brief tram ride away, in the district of Kalchbühl. Here, the Giger Bar, opened in 1992, banished from the ancient centre to the base of a conventional modern office building, has an interior of black and silver.

Torso makes a reappearance behind the bar, but the main features are Giger’s Harkonnen chairs and tables.

China’s famous train documentary photographer Wang Fuchun dies aged 79

The bar serves an Alien cocktail among more familiar options, and what seem to be death masks of Giger and others are hidden in niches in the counter.

Giger’s triumph with Alien was also his downfall. On the one hand, film fees and merchandising royalties were substantial, but having had some solo exhibitions he now found himself labelled a film designer or commercial artist, and the fine-arts world closed its doors to him.

To Giger’s delight, the Château de Gruyères, a fortress with 11th-century origins turned country house, decided to stage a major exhibition of his work in 1990 that led to a permanent presence there.

He bought an ancient building near the chateau and created a museum to his own art, with another Giger Bar opposite.

Gruyères, in the western canton of Fribourg, famous for its rich dairy products and Switzerland’s best-known cheese, is little more than a single ridge-top street sloping up to the chateau. At one time an artists’ colony, its interiors include panels painted by Corot, the French Impressionist.

This is everyone’s idea of medieval Europe, the solid premises of merchants and artisans sheltering beneath a hilltop castle with views in all directions across surrounding farmland to distant, spiny, snow-capped mountains.

As with Chur, the contrast between the picture-postcard prettiness of the town and Giger’s gloom is striking, but especially so after stepping into the museum and entering the artist’s mind, past a large cast of Birth Machine, a cross-section through a pistol with baby-shaped bullets in its magazine.

The museum’s current director is Sandra Beretta, Giger’s right hand, collaborator and lover for eight years from 1991, who only recently resigned from a long career with Swiss television to tend his memory.

There’s work here from all periods displayed on several floors, including paintings created using ink and a tea strainer before the invention of the airbrush.

“Maybe 90 per cent we speak about Alien and maybe 10 per cent of Ruedi’s great art,” says Beretta, wearily. “The people who say only Alien, it’s because they don’t know Giger. They just don’t know.”

Among the xenomorphs (the fictional extraterrestrial species of the antagonist in Scott’s movie) and biomechanoids, there are vulvas, penises, condoms and babies in plentiful supply, and there’s a general warning that visitors should be older than 16 unless entering with parental consent, with one room featuring particularly gynaecological art.

“I think in 1968 it was erotic more than anything, and now everything is prudish,” says Beretta. “You can make a movie with war, but to show a naked woman or naked man? No, no, no - it’s terrifying.”

Giger went on to design album art for others including Debbie Harry and Chris Stein of Blondie, and to work on many other films, such as Species (1995). One floor of the H R Giger Museum has a smaller copy of the skull-surrounded, bare-breasted female torso that was erected in New York’s Times Square to promote that film.

“On the t**s you see my tongue,” says Beretta, proudly - a cast of it in a curled form has replaced the nipples.

Giger, she says, was in fact a shy and sensitive man. Frequent images of goats’ heads didn’t make him a Satanist any more than Egyptian elements made him Egyptian.

Nor was he religious, abandoning Catholicism in adulthood. And what he found frightening in the cathedral as a child was in fact the image of Jesus’ crown of thorns, she says. A table with a transparent top supported by four crucified Christs, two inverted, was originally installed in the Giger Bar in Chur, until the bishop denounced it as blasphemous and demanded its removal.

And despite the distorted female imagery, Giger was no misogynist either.

“He told me his religion is women,” says Beretta. “But he preferred to have a witch to a fairy.”

The H R Giger Bar outside is even more extravagant than the one in Chur, not merely furnished by Giger but its interior, like an alien rib cage, entirely conceived by the artist.

Giger completists may also venture out to three terraced houses that Giger owned in Zürich, two kept blacked out so that when Beretta and he were working there together, she was often unsure whether it was day or night.

The houses apparently have the most extravagant of Giger’s interiors, along with a garden full of statues and a model railway with a train made from skulls, a version of which is visible in Gruyères. But there’s no public access.

Giger died in May 2014 and, at his own request, was buried in the cemetery at Gruyères, just below the chateau, beneath a black slab carved with similar biomechanical patterns to those in the fountain in the town of his birth.