Invasive alien species in Switzerland - Schweizer ...

Invasive alien species in Switzerland - Schweizer ...

Invasive alien species in Switzerland - Schweizer ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

29<br />

06<br />

> Environmental studies<br />

> Organisms<br />

> <strong>Invasive</strong> <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong><br />

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity<br />

and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong><br />

&%&&&&&0?0&&000&?0?/^/&0&&&%%&&&&&&&%&&&&&%&&&0???00???0//??/&&&&&&&&&&&&&0&0&&0&&&&&00?000?0??//0&&&&00&&&%0??00??000?000???&0000&&&&<br />

&&%%%&&00/?0000???//&0&&&&&&&&%&%&&&0&&&&&%&&&00???0???????0&0&&&&&&&&&&&%&&&&&0&&00000?/0???///??0&&&&0&&0000?0??000?00000?000000&0&&<br />

&00&?&0&??/?&00?/^&&0&&%%&&&&&%%%&0&00&&&&00&00????00??///&&&&&&%&&%%&&&&&&&&&0&&&00?0&0/000?////?0&&&0???????0&&&&000&%%%&0&000000000<br />

&&&&0&00???/?//^?0&&&&%%&%&&&&&&&%0&&0&&&&&0?00???/&??//&&0&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&0?&&0??000??0??/////0???//?0&0&&000&&&00000&000??0000000<br />

0&&0000&00?&//&0&&&&&&&%&%&&&%&&&&&0&0??0&000?0/?0??//&00&&&&&&&&&&&&&%&&%&&&&0???000??00/???/?//?&&00&&&00000&000&&&00&000?0?/??00000<br />

&&0000&0000?%&0&&&&%&%%&0&%%&&%0&&&0&&0??/0&&?????//%&&&&&%&&&&&&&%&&0&&@@%&&00?/?00??/??0/?////0&&&%&&&&00000&&00&&&&&&&0000??????0??<br />

&&0&?&00&?/%?&&&&&%&@%%%&&%&&&&0&&&0?0&?0?000???//?&&&&&&&&%&&%&&&&&&&0&&&&&000?//0???/?00?///?000&&&&&&&&00?&&&&&&&&&&&&00000??/??0?0<br />

&0&00&&??^&0&%%%&&&&%%%&&0&&&&0&000000&??0?????/?&0&&%&0&&%&%%%&%&&&&&0&&&&00?0????0??///?//?00000&&%&&&0&00?00&&&00&&&&&&0?0???//?&00<br />

&&&00?///%0&&%%&&%&&&&&&&&&&%&00&??000?/?//??^^00&&&%&^,““›&%%&&&&0&0&0&&&&0&0??///???/?//?&&@%0000&&&&&&0&&0?000000?&&&&&00?0???//0&0<br />

&0?&0/?/&0&&&%&%%&&%&&&&&&0&&0&0&00??0????//^&0&0&&%&%000/›;&&&&//;&&&0?0&000???////??//?&&&@@&&?000&%&%&&000??&0&000000&&0????////000<br />

&00???/%0%%%%%%%&&%%%%&&&&&?&0&??0&&?//&0?^%0&&&&%&&&&&&›››^^&%/›“/&&00?&&&0???//??/?/?&00&&&&&?00000&&%%&&000??&&00000&&&00?/??///?0&<br />

0?0?/?&&&0&%&%%%&&@&&&&&%%&?&0%0&??/?///^/&0&&%%&%&%&,;;“““%&››;›/?&000???&???^/////?&00&&0&&&00??0000&&%&&0000?&00000?0&&&0?//?/^/?0&<br />

??&/?00&&%&&0&&%&&&%%&&00&00000&?????/^0&0&&&&&&&&&&›“^››^,/;/&@^;^?^;&@???????//^/&&&&&&&&&0&&&000&0&&&&&&&&00?0&0000??000?0//?/^/?00<br />

0?/^0&&%&&@%%&&&%%&&%&0&%00%/0?0&0?//^0?&%&&&&&&%%&?/“““““;,/““^/%^››^?0?/////?//0&&&&&&&&&&&000?000&&&&%%&&&&0??00000???000?//?///?0?<br />

//?00&&&%&&%%&&0&%&&0&0&%0?//?0/&?/^^&0&%%&&&%&&&%%??,““““““^^“““^@@,@%@?/?/?//?&&&%%&0&&&&&0&&0&0?000&0&%%&&&0???0&&00???00///////?00<br />

^0?&&%&&&@%%%?&00&&&&?0???0?0?/^/^^?0&&&%%&%%&%&&&&?/?;“““^“““““““›0&›^^@?@?^/&00&&&&&&00&&&&&&00000000?&&&&&&&????0&0?0?/?0?////??&&0<br />

%/&%&%@@%%%%&0&&&%0?0???///???//^?&0&&&&%&&%%&%&&&;““^/›“,“›@“““,;,@0;^;“›//&0&&&00&&&&&&0&&&%&&00&000000&%%&00?0?/????0?//??//?&00000<br />

?0&&&%@%@%&&%&&&&?0%0&?0/??0?//^%?&%&&%%&&&%&&%@&0&/^,^““/›““““““/@@0,““^,,@@%&&%&&0&&&&&&00&&&&&0&&&0&???&&&&&00?/?????/?///?00000000<br />

&%&&&%%%&&&0&&?0?&&&0&?/0/?&&^^%0&0%%%%%%%%%&@%%&&&00&?^››/›“““@““@@@^?,“,““%&%&&%&%&0&&&&&0&&&&&0000000??0&&&00??/?????//?&00000??000<br />

@%%%&&%&&%&&%&&?0??&0/^//?0^/^00&%&&&&%&&%&&&&%%@%00&&&??^,“““““““^?@@?“““^,;%%&&&&&&&&&&&&0&&&&&&&00000&??&&&&?????/?/?&&000?00000?0?<br />

@%%@%&&&0%&&0%0&?&?&^??/?&//%?&&%%&%&&%%%%%@&&%%&%&&&0%%?/“““›,““““““@@“&““;“,%0&&&&&&&&%&&&0&0&&&00000000?0000?/???/&&&&000???00000??<br />

&%@%%&&&&0%&0%%&&?0?//^0?/^%0&@%%%%@&&%%0&%%@&%%%%0&@%&&/^““/››“““““,“&?@,““;,›@&0&&&&&&&&&&&0&&&&???0??0??????//^/&&&&&0???/?/00000//<br />

&&&%%%&0&00&&&??0//?///?/^?0&%@%%%%%&%&&%%@%%&&0&&?0&%00/›^/›^››“““?“““›@?%“›@“››//0&&&0&&0000?00?000?0????/?//^0&&&0&&&0?//?//??00??/<br />

@%@%@%&&000%&0?0/0^^?/^^%0&0&&&&&%%%@@%&&%&&%%&%&&&00&?0/0/^^?››““/,“““,“0@,“,“;,“??&%%&0&&0&??00?00???????//000000000000/?/?//^??0?//<br />

@&&%%@@&&?/&%???0//??/0&0&%%&%%%%%&@%@@&&%@&%@%&@0/0&?///?/?^^^;/,//^“““““@%““““;,;0&0&&0000?00??/????????^?&&&000000??????//////???//<br />

&&@&@%0&&?0/?&/&0?^/^?&&&&%%@&&%%%&&%%%&%%%@@%&@%%/%&??^^///^›0???//?^,“““““““,““““?/0&000?00??????//?//^?0&&@&?000???/?0???/??///?/?/<br />

@%%%&0&0&000?^/?^/^^&?&%@%%%@%%&@@&%@%&&0&@%&&&0&0?&?0/////^›%??0&0/?^^^;““““““““““??00/00????//?/??/^^0&&&&&0&0000????/???/////^?/?//<br />

&%&%&0%0?&00///@/^^@?&@@@@%%%@&%&@%&@@%&?%&%&0&0??^///?//^^^@?0&&&&@%/^^^“›“““““““›?00?????/?/?/^/?^^&&0&&&&&&&??0??0?///??///???/?//?<br />

0?&%%&&00&//?0//^/%&00&%@@@%@@%%&&&%%%@%%&&&00/^?????///^^%0000&%%&000?/^›››“,““›/^///?0/??////?/^/&%%&&0&&&%&%0??&??///^?0/??/?/////?<br />

%0??&&0?00^/?/0/%?&&&&&&%@&@@%%%%%&&%%0&&?/?&^^›//^^?^^^@?&&%&0%&0&&000?^/›^^›^,›^/???/?/^/?^/^^^&0&&&&&00&&@0&&00/???0//?????////////<br />

%%00///&/??/0/^%?0%%@%@&%0&%&%%%@%%&0%&?&??^//^0?%00^?@0&0&&%&0&&&000&&?^/^^//////?///?/?^^?/^/&0&0&&&&&000&%%%0&?^0?///^/??//??//?///<br />

&&&&?0/^?///^^&?0&%&%@@@@%&&%&%&&&%&?0/??^^&?00??&/^0&&%%&&%&&&&%&0000?&??0/?0?/?/??0/^^?^/^^%&@@%&0&&000????&0/?//0//^////??/////////<br />

0??0??0/0////&0%%@@%&%&%%%&%%&&&&%&&?0/?/?//?&&//^^%0&%%%@&0&&%&0??&&?0?00?//0?/??///^//^^^&0&@@%&0&00&&00????//?/^//^?^^^/?/////^//^/<br />

0&?//^^/^/^00&%&@@@@@%@&@&&&&00?&0%////0^?^^^/0&^000&%@&%%@&&%&0?0000?/?0?&?////?/^?///^^%000&&%&&&&?0&0?0?/&??/?/^//^/^/^^?/////^//^^<br />

/0?&?//?^^%000%&%@%@@&@&@%@&%00&??/?0//^&^^?^&^^&00&&&&%&%&%000/00?0^????&0/?///^^?^//^?0&%&%%0&&&0&00&&000/0???///^//^//////////^///^<br />

&&0&^//^^0?&&00%%%%%@@&%%%&&%0????^0/›0/^/^?^/@0&&&&&&%%%&%&&&0&?????00?&??/??///0//^0%?0&&%&@&000&0?&????//?////^/^?/0//^^/?/^^?^//^^<br />

^^?&?0^^?0&%%%%%&@@@&?0&&??%0^/&?&/?^^?^^^^^&0&0%&%%&&00&00&?&??00??/?/?^?/??/^///^^%&&&&%%%&&0&&0??&??&//^??//^^/^^/^/0/^^^//^^/^^^^/<br />

%^??/^%??&%%@@%@%@%%%0&&&&?0/^/^/^?/^^^^^//&&0%&&&&%&%%@0&0&?00&00&/&?/?0/^/?^^/^^%00&&@@&&&&00&&?&0000??/////^?^^^^/////^^^//^^^^0&00<br />

^0^//@?&%0%%%&@@%&&0%&@&&//////^//^0^/?^^&00%%%%0%%&%&%&&&?0000?0?/0??//^^/^/^/^/&0000&%%%%0&&00000%&?/?/^?////^^^^^///^^//^//^^/000??<br />

/&^^@?%%%%%@@@%@/&0&?&?&&%^^0?^^/^^/^››?000&%%@@0&00&&%%&%/0?/00//???^//^/?^^^^@&00%@&&&&%%&?0????0&&0?//////^^/^^^^//^/0?0^^/000000??<br />

^^?00?&&@%&@@&@&&??&?/?^^/^?^//?››^/›?%00%@@@%%%%&&%&&&&&0000?/&//??//›^/&^^^&?&&&&&@0&&&0&000?&?/0/^/?/?^^^^/^^^^^^^///?/^&&000?00??/<br />

^&/&&&00&&%%0?%&&00&^/^?^//›^&///^^›@0&0%%@@@%&&&&&%0&&000?/?????//?^^/^^^^^000&&%%0&&&&%@^&?/0///?;›/?/?^^//^^^^//^^/^^?&000000????/^<br />

&0&@@&&0@%&&&&?&/^&&^/??^^›?^/^^^^&&0&&%0%@@%&&@&0&&&??&0/0^/?0/??//?^^/^/@00&&&&&%00^00%/?“/??//?^“›?//^^//^^^^^^^^^?&0&00?00?0????/^<br />

0@0%%%0?000/?0&/%/?0//??^0/^?//››&00%%%%%&@&&&00?00&&&00?&/0^0/^^›^///^^?0&00&&&%0????“,?0&/;“?//›““^›;^^^/^/^^^^^^?&00000?000???/?//^<br />

%0&&0&&?0&?0??//^^^//^0^/^›/^^›@00&&%%%%&&&@&&000????%???/0/?^?^^^///^^@00000&&&&&&&0/^^^;^›/“,%““;^%;“›^^^^^^^^^?&000??&00??????//&?^<br />

&&/&&&0&?00?00/0/&00?/›?^?^^›/000%0%%%&&&&@&@@&0%&0%?00?/?//??//^^0^›?0@0&?&&&&?&0?%0??0/››%““,“›^››%0^“›^?/^^^/00000?00%&&???????//?/<br />

&?&?&%?00???^//^&//?/^^^›^››@?&%%%@%&%0@0&@@%“;@&^??/00&?^??^^^?/^^^&0&0&00?&%&&&&000&,??@@@@&&,›/^“0^%,;^/^^00000&&0?0&&&0??/?0?/^/^^<br />

@@&&&/&0??//^???/^/›^^//^›@?00%%@@/%@@@@?%@@&›@@@@@%?/0?//^/^^^^^?%000&0&&0&?&&&00&›0/&@@@@@/@%“/›0@@^/“›^^^&0&%000&&0?0?0?0?/??///^^^<br />

/?0?&??//?^0??0^/^^^^?^›/&?&&%@&%0/^“;0›;@@@0›?@@@@@%›&//^///^/^00&0&?&0%&&?0???/&?0@@@%@›^,^““&@@/0“;“^“›&?00000???0?0?000?////?^^^//<br />

/&%&?00????00?//^^0/0^^@?0&%&&@&%@?@^,@@/@@@@@@@@@&@@@%%/?^/^››%0&0&&&0&%%?0?^?/^@@@@@;›^/““,0,;,“,^“,““?/000&?0?&0?0?0/00??/?/^/^^^^^<br />

/&&///?///?0^^›^0&%%^›%00&@@@0@?,&?““@@@?;^^@@@@&@?“@@@%%“?//0&00&%&%%%0&&&&/›;@@@@^›?›““,?›““,?“““““““^,^&0000?00&/??0????///^^//^^^^<br />

/&/&????//?^&?0&?/?^%0?0%@@@&/&&››,““%@/%&@@@&›%&@@›%@@@“/0›??&&&&%&&%00&^,›““^“^^?“&“/^;“,;““&““,“““0^››,;0&&?0/0?//0?????//^^/^^^^^^<br />

^00?/0?/0^//0/%0^?›@0&0%%@%0&0/^›@@@“““&%@@@@@@%%@@%&@@%““&&&00%%&%@@››;/;“››““^““,^“,,›““,/“&›““““,^“^//^0&000??/?????0////^^^^^^^^^›<br />

›^^›^/??&^^^&?/^›@&?%%&&??&/?^^/^@@@@;/&%›“%%%%“““&%%?%&&“&0?%&&%?&^““,,,^›^^;;;›,“;“&“›?;@^“@““““?;^//?0??00??////??/^?/^^^/^^^^^^^››<br />

@%^&0?/^›››››››/@&??/?/^^?/^›^^0?›@@?/%&/“““&%&;“““%%@%%^&&0?&&&%&&›“““““,“,›“““;“;“/“%^?@“,“““““?^?0000/^??00?///???/??//^/^^^^^^^›^›<br />

00&0??&&@@0&&%/@@%&&?/^››/››››/^^^“››/^&&??00&&&/&&&&&››??›?/000?0&/;“““““““““““,“““/%“,“?“““,““;^?0000&^^/??/////^?^///?/^^^^^^^/^›^›<br />

&&&&%&0&&&&@%00???????0@@@%%&0/››;,“››““““??????000&0,“““/^^^0%///?//››“;““““““““““;“^“““““,,“0^/0&&&000^^/?0//??//?/^//^^^^^^^^^^›/^›<br />

%00&&&&&&&&0@&&&&0&&&&%&?0&00?^/&&^;“›“““,›^^//^›////““,/^^;^&?^//^/^›^›?›“““,›“““,“,,,››,^›00^0000?/?&??/0^//?//^//^^/^^^^^/^^^›^›^^?<br />

%%&%@@%&&&&0&@?%&%&&@%&%&%&&&&0^?//^;“›,“,,,,;;““^^^›››››;^““^^/?/&/››^//^^››,^“›;;›^0^›^^›0/?&@@&??//??^?^^^/^^^/^///^/^^^^^^^^›››^??<br />

%&%@%%%%&%&&&?0/&@@@@%%%&&@@@@%?&?^^/›““^,“““““,,,,“““,,›;/0^›^››^›^^^^^^^^0/›^^^^^0&/^›^^%?????0??^^//^^^^^^^//^^^/^^^^^^^/^^››››//??<br />

&&%@%%%%%%&%&&%?/%%@@@@@%%@@@@@%@&0?//^›““““““““““““““““›››/?^?%%%&&?0^››^›^›^^^^^%0?^››%?/?/@0???/^?^^^///^/^/^^^^/^^^^^^^^^^›››?/???<br />

@%%%%&@%&&%&&0?@?%@@%@@@@@@@%@&0@@&%0&0/^^;“/“““““““““;^?/&%&&00??00?///&@@%&%/^›^››^^^%?////?&&/&^?^///^/›^^^^/^^//^^^^^^^^^^››???/??<br />

%@@%@@%&&@@@&&0?%^?&@&&@@%%@@@@@%@@@@%%&0^?/^&/%%@,0?^?0&0/0&&0&?&0&&@@@00?00/???&%&%%&?/^/^/^^&^^?^/^0//^/^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^????/?/<br />

%%@%%%0%@@@@&0&&0/0@&&%@@@%@0%%%%%&%%&&%%%0??›&^@@@@&@%&&&0/?&0?&%%0%0%%&%%&0//&0???/&@%@%&0/^›››^^^^^^^^^///^/^›/^^^^^/^^^^^›????///?<br />

%@&0%%%&@%%&%&&&0%^??%%%@%%%&&&@%@@%&&@@%&@%0?^@^0?&^^&&&%%^???&^/%&@?000&0&000?%00^/0?^%?0????0&%%&00/›^/^^^^^^/^^^?^^^^^^^^/????////<br />

&0&@%@%%@@@%@%0&?&@^??&&%&%&&&%@@&&%&&@%%%%&0/?/%^00&0&%%&%%&&0&??&&%@&&0%0?000/??00/?00?/?///0??????0????0&&&??/››^^^/^^^^^&//?/////?<br />

&%%%@%&@%@%&&&0?&&/%^&&&&%%&&%&&&&&0%%%%&%&&&^0&?%^?%?%0/0?^?@@@?^^0&&0&&&?%0&?//??&?0??/&//?////??%/0????@??00???&&&&&0???&//?////?//<br />

%&%%%%%@%%%&%0&&&&0??//&%??&%&%@%&&&%%%%&&%0/00%&^%^/?00^^^/^›^?^^^/%&&&&0?&?00/0??00&0?/^0000?0//??^??//&&/?00/%????00?0?0&&0?//////^<br />

@%%%%%&%&%&%&&%%%&&???0??&@@@%&%%00&&&&&&&&?&0%%0?/%?//0//&/??%?/?^/?/0???00?&??0?/%@?0&^?/?00//^/?0/^???0?^?/?^/??/^?/^/???//??0&&?^^<br />

00&&%&%&%%@&%&@%000?0?%/?0?%&0@%&&%%&&00&&?%%&?&0???0/^/?/?/?%//??/&?0&0?/00^?&/0?0&%&??&/?^?///?0/??^/0/0?^?0/^^/?/^///??//?0^?//???0<br />

&&&%%%%&%%%&%%&&&0?&&??/^%?0@&?/&&0&?%%%&?&&@&&/0/0/0?^?/^^?//0^00/?&?0?&^^/0?^^@?0@&0???//^^?/////?/0?////^0?/^^///^?/?&?^//^/?&&0/^/<br />

%&%%%@%%%&0%%@&%?0&&&0?%^0?&&/&&&&%%%&%00&&&&%0&0???&?^0^^/&?^/0/^/^?/?/?0&0/^0?0%%@0???&&0&^^/00?^0?/^^?//?^/^^//?/^//???^^////^0&/^/<br />

&&%%%%&%%0%%%&&000&&&%0?%^^//&@&&0&&&&&?%&0%&&00&/0%@00/%/?^/?^^^//^???^0?00?/????%&0?0?&0%&^^^^/0///^/??/?^^0//^^/^^/^?^/^^////?/0?^^<br />

&%@%&%%&%%&&%&&?&%&0&00/0%/?@0?0&&&0??/&@&&0&&0?/?00?0??/&^^?0^/^^^/^//?^??^0/?^???%0&0?/??%?^^?//?/^?^^^//^//^^^//^^^^?/^^^^////^??^/<br />

?%&0%&&&&%%&0?0&&%&&&0&0%?&^/?&0&%000?&&&&0&00??^0&?0?0???&^/^??^^?^/^//?//&^^//??0&???0?0/?%^^^?//^?^^^//^////^^^^^^/^/^^^/^??////?^?

Environmental studies > Organisms<br />

><br />

<strong>Invasive</strong> <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong><br />

<strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong><br />

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity<br />

and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong><br />

Mit deutscher Zusammenfassung – Avec résumé en français<br />

Published by the Federal Office for the Environment FOEN<br />

Bern, 2006

Impressum<br />

Editor<br />

Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN)<br />

FOEN is an office of the Federal Department of Environment,<br />

Transport, Energy and Communications (DETEC).<br />

Authors<br />

Rüdiger Wittenberg, CABI Bioscience <strong>Switzerland</strong> Centre,<br />

CH–2800 Delémont<br />

Marc Kenis, CABI Bioscience <strong>Switzerland</strong> Centre, CH–2800 Delémont<br />

Theo Blick, D–95503 Hummeltal<br />

Ambros Hänggi, Naturhistorisches Museum, CH–4001 Basel<br />

André Gassmann, CABI Bioscience <strong>Switzerland</strong> Centre,<br />

CH–2800 Delémont<br />

Ewald Weber, Geobotanical Institute, Swiss Federal Institute of<br />

Technology, CH–8044 Zürich<br />

FOEN consultant<br />

Hans Hosbach, Head of Section, Section Biotechnology<br />

Suggested form of citation<br />

Wittenberg, R. (ed.) (2005) An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their<br />

threat to biodiversity and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong>. CABI Bioscience<br />

<strong>Switzerland</strong> Centre report to the Swiss Agency for Environment,<br />

Forests and Landscape. The environment <strong>in</strong> practice no. 0629.<br />

Federal Office for the Environment, Bern. 155 pp.<br />

Design<br />

Ursula Nöthiger-Koch, 4813 Uerkheim<br />

Fact sheets<br />

The fact sheets are available at<br />

www.environment-switzerland.ch/uw-0629-e<br />

Pictures<br />

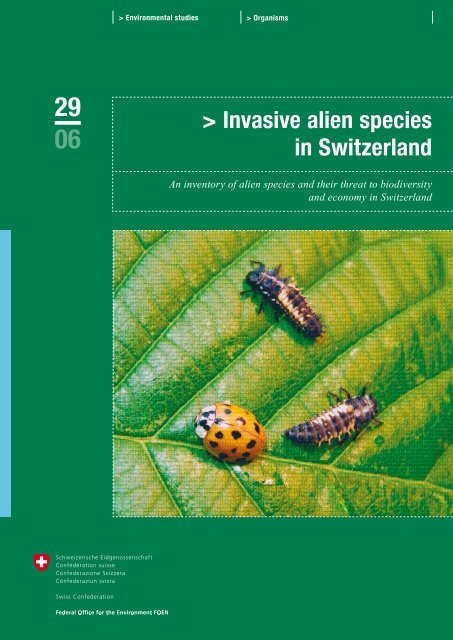

Cover picture:<br />

Harmonia axyridis<br />

Photo Marc Kenis, CABI Bioscience, Delémont.<br />

Orders<br />

FOEN<br />

Documentation<br />

CH-3003 Bern<br />

Fax +41 (0)31 324 02 16<br />

docu@bafu.adm<strong>in</strong>.ch<br />

www.environment-switzerland.ch/uw-0629-e<br />

Order number and price:<br />

UW-0629-E / CHF 20.– (<strong>in</strong>cl. VAT)<br />

© FOEN 2006

Table of contents 3<br />

Table of contents<br />

Abstracts 5<br />

Vorwort 7<br />

Summary 8<br />

Zusammenfassung 12<br />

Résumé 17<br />

1 Introduction 22<br />

1.1 Def<strong>in</strong>itions 23<br />

1.2 <strong>Invasive</strong> <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> – a global overview 24<br />

1.3 Status of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> 28<br />

1.4 Pathways 28<br />

1.5 Impacts of <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> 29<br />

1.6 Discussion 31<br />

1.7 Recommendations 32<br />

1.8 Acknowledgements 34<br />

2 Vertebrates – Vertebrata 36<br />

2.1 Mammals – Mammalia 36<br />

2.2 Birds – Aves 44<br />

2.3 Reptiles – Reptilia 52<br />

2.4 Amphibians – Amphibia 54<br />

2.5 Fish – Pisces 55<br />

3 Crustaceans – Crustacea 65<br />

4 Insects – Insecta 71<br />

4.1 Introduction 71<br />

4.2 Coleoptera 73<br />

4.3 Lepidoptera 75<br />

4.4 Hymenoptera 77<br />

4.5 Diptera 79<br />

4.6 Hemiptera 80<br />

4.7 Orthoptera 82<br />

4.8 Dictyoptera 83<br />

4.9 Isoptera 83<br />

4.10 Thysanoptera 83<br />

4.11 Psocoptera 84<br />

4.12 Ectoparasites 84<br />

5 Spiders and Allies – Arachnida 101<br />

5.1 Introduction 101<br />

5.2 List of <strong>species</strong> 102<br />

5.3 Species of natural habitats 103<br />

5.4 Species <strong>in</strong>, and <strong>in</strong> close proximity to,<br />

human build<strong>in</strong>gs 106<br />

5.5 Greenhouse-<strong>in</strong>habit<strong>in</strong>g <strong>species</strong> 108<br />

5.6 «Banana spiders» and terrarium <strong>species</strong> 109<br />

5.7 Discussion and recommendations 109<br />

6 Molluscs – Mollusca 113<br />

6.1 Snails and slugs (Gastropoda) 113<br />

6.2 Bivalves (Bivalvia) 115<br />

7 Other selected <strong>in</strong>vertebrate groups 121<br />

7.1 Nematodes – Nemathelm<strong>in</strong>thes 121<br />

7.2 Flatworms – Turbellaria, Plathelm<strong>in</strong>thes 122<br />

7.3 Segmented worms – Annelida 122<br />

7.4 Centipedes and millipedes – Myriapoda 123<br />

8 Lichens (Lichen-form<strong>in</strong>g fungi) 124<br />

9 Fungi and a selected bacterium 125<br />

10 Plants – Planta 128<br />

10.1 Introduction and term<strong>in</strong>ology 128<br />

10.2 The native and <strong>alien</strong> flora of <strong>Switzerland</strong> 130<br />

10.3 The geographic orig<strong>in</strong> of <strong>alien</strong><br />

and naturalized <strong>species</strong> 131<br />

10.4 Status of the <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> of <strong>Switzerland</strong> 133<br />

10.5 Naturalized <strong>species</strong> of <strong>Switzerland</strong> 134<br />

10.6 Life form 135<br />

10.7 The habitats of <strong>alien</strong> plants <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> 136<br />

10.8 <strong>Invasive</strong> plant <strong>species</strong> <strong>in</strong> Europe 138<br />

10.9 Discussion 139<br />

Fact sheets 155

Abstracts 5<br />

> Abstracts<br />

Globalization <strong>in</strong>creases trade, travel and transport and is lead<strong>in</strong>g to an unprecedented<br />

homogenization of the world’s biota by transport and subsequent establishment of<br />

organisms beyond their natural barriers. Some of these <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> become <strong>in</strong>vasive<br />

and pose threats to the environment and human economics and health. This report on<br />

<strong>alien</strong> biota <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> lists about 800 established <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and characterises<br />

107 <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> (IAS) <strong>in</strong> Fact Sheets: five mammals, four birds, one reptile,<br />

three amphibians, seven fish, four molluscs, 16 <strong>in</strong>sects, six crustaceans, three spiders,<br />

two «worms», seven fungi, one bacteria, and 48 plants. A general chapter expla<strong>in</strong>s<br />

some common patterns <strong>in</strong> pathways, impacts and management, and gives recommendations<br />

for the management of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong>. The ma<strong>in</strong> body of the report is organised<br />

<strong>in</strong>to taxonomic groups, and <strong>in</strong>cludes an overview, lists of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong>, Fact Sheets on<br />

the <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong>, and an evaluation of the status, impacts, pathways, control options<br />

and recommendations. The Fact Sheets summarize <strong>in</strong>formation on the <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong><br />

under the head<strong>in</strong>gs taxonomy, description, ecology, orig<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong>troduction, distribution,<br />

impact, management and references.<br />

Mit der zunehmenden Globalisierung nimmt auch der Handel, Verkehr und das Reisen<br />

zu und führt zu e<strong>in</strong>er noch nie dagewesenen Homogenisierung der Biodiversität;<br />

Organismen werden über die natürlichen Grenzen h<strong>in</strong>aus transportiert. E<strong>in</strong>ige dieser<br />

Neuankömml<strong>in</strong>ge können sich etablieren, und wiederum e<strong>in</strong>ige von diesen werden<br />

<strong>in</strong>vasiv und bedrohen die e<strong>in</strong>heimische Vielfalt, richten wirtschaftlichen Schaden an<br />

oder schädigen die menschliche Gesundheit. Dieser Bericht über die gebietsfremden<br />

Arten der Schweiz listet über 800 etablierte gebietsfremde Arten auf und stellt die 107<br />

Problemarten <strong>in</strong> Datenblättern vor: fünf Säugetiere, vier Vögel, e<strong>in</strong> Reptil, drei Amphibien,<br />

sieben Fische, vier Weichtiere, 16 Insekten, sechs Krebstiere, drei Sp<strong>in</strong>nen, zwei<br />

«Würmer», sieben Pilze, e<strong>in</strong> Bakterium und 48 Pflanzen. Das erste Kapitel erläutert<br />

e<strong>in</strong>ige allgeme<strong>in</strong>e E<strong>in</strong>führungswege, negative E<strong>in</strong>flüsse und Gegenmassnahmen und<br />

gibt Vorschläge für den Umgang mit gebietsfremden Arten. Der Hauptteil besteht aus<br />

den Kapiteln zu den e<strong>in</strong>zelnen taxonomischen Gruppen. Die Listen werden begleitet<br />

durch e<strong>in</strong>en erläuternden Text, die Datenblätter stellen die Problemarten vor und<br />

schliesslich wird e<strong>in</strong>e Auswertung der Situation, der Auswirkungen, der E<strong>in</strong>führungswege,<br />

mögliche Gegensteuerungsmassnahmen und Empfehlungen zu den jeweiligen<br />

taxonomischen Gruppen gegeben. Die Datenblätter bieten Information zu Taxonomie,<br />

Beschreibung, Ökologie, Herkunft, E<strong>in</strong>führungswege, Verbreitung, Auswirkungen,<br />

Ansätze zur Gegensteuerung und e<strong>in</strong> Literaturverzeichnis.<br />

Keywords:<br />

harmful organisms,<br />

<strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong>,<br />

<strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong>,<br />

biodiversity<br />

Stichwörter:<br />

Schadorganismen,<br />

gebietsfremde Organismen,<br />

<strong>in</strong>vasive Organismen,<br />

Biodiversität,<br />

Neobiota,<br />

Neophyten,<br />

Neozooa

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> FOEN 2006 6<br />

La mondialisation implique une augmentation du commerce et des transports et en-<br />

traîne une uniformisation sans précédant des biomes par le transfert et l’implantation<br />

des organismes vivants au delà de leurs barrières naturelles. Certa<strong>in</strong>es de ces espèces<br />

exotiques deviennent envahissantes et représentent une menace pour l’environnement,<br />

l’économie et la santé publique. Ce rapport sur les organismes biologiques exotiques en<br />

Suisse <strong>in</strong>ventorie environ 800 espèces non-<strong>in</strong>digènes établies dans le pays et détaille<br />

107 espèces envahissantes sous forme de fiches d’<strong>in</strong>formation : c<strong>in</strong>q mammifères,<br />

quatre oiseaux, un reptile, trois amphibiens, sept poissons, quatre mollusques, 16<br />

<strong>in</strong>sectes, six crustacés, trois araignées, deux « vers », sept champignons, une bactérie et<br />

48 plantes. Un chapitre général explique les modes d’<strong>in</strong>troduction pr<strong>in</strong>cipaux des<br />

espèces exotiques et leur impact sur le milieu. Il donne également des recommandations<br />

sur la gestion et la lutte contre les organismes envahissants. Le corps pr<strong>in</strong>cipal du<br />

rapport est présenté par groupe taxonomique pour chacun desquels sont proposés une<br />

discussion générale, la liste des espèces non-<strong>in</strong>digènes, les fiches d’<strong>in</strong>formation sur les<br />

pr<strong>in</strong>cipales espèces envahissantes et une évaluation du statut, de l’impact, des modes<br />

d’<strong>in</strong>troduction, les méthodes de lutte et des recommandations générales. Les fiches<br />

résument pour des espèces particulièrement envahissantes ou potentiellement dangereuses<br />

les <strong>in</strong>formations sur la taxonomie, la description, l’écologie, l’orig<strong>in</strong>e, l’<strong>in</strong>troduction<br />

en Suisse et en Europe, la distribution, l’impact, la gestion et les références<br />

bibliographiques.<br />

La crescente globalizzazione implica un aumento del commercio, dei viaggi e dei<br />

trasporti e determ<strong>in</strong>a un’omogeneizzazione senza precedenti della biodiversità a seguito<br />

del trasferimento e del successivo <strong>in</strong>sediamento di organismi viventi oltre le loro<br />

barriere naturali. Alcune di queste specie <strong>alien</strong>e diventano <strong>in</strong>vasive, m<strong>in</strong>acciano la<br />

biodiversità locale, causano danni economici o sono nocive per l’uomo. Il presente<br />

rapporto elenca le oltre 800 specie <strong>alien</strong>e presenti <strong>in</strong> Svizzera e propone delle schede<br />

<strong>in</strong>formative per le 107 specie diventate <strong>in</strong>vasive. Si tratta di c<strong>in</strong>que mammiferi, quattro<br />

uccelli, un rettile, tre anfibi, sette pesci, quattro molluschi, 16 <strong>in</strong>setti, sei crostacei, tre<br />

aracnidi, due «vermi», sette funghi, un batterio e 48 piante. Il primo capitolo illustra<br />

alcune delle vie di penetrazione più comuni di tali specie nonché il loro impatto negativo<br />

sul nostro ambiente. Inoltre, propone possibili contromisure e raccomandazioni per<br />

la gestione delle specie <strong>alien</strong>e. La parte centrale del rapporto è suddivisa per gruppi<br />

tassonomici. Le liste sono corredate di un testo esplicativo, mentre le schede trattano le<br />

specie problematiche. Inf<strong>in</strong>e, il rapporto presenta una valutazione della situazione,<br />

dell’impatto e delle vie di penetrazione, alcune contromisure e delle raccomandazioni<br />

concernenti i s<strong>in</strong>goli gruppi tassonomici. Le schede contengono <strong>in</strong>formazioni relative a<br />

tassonomia, descrizione, ecologia, provenienza, vie di penetrazione, diffusione, impatto,<br />

eventuali misure di gestione e <strong>in</strong>dicazioni bibliografiche.<br />

Mots-clés :<br />

organismes nuisibles,<br />

organismes exotique,<br />

organismes envahissants,<br />

diversité biologique,<br />

néophytes,<br />

animaux envahissants,<br />

plantes envahissantes<br />

Parole chiave:<br />

organismi nocivi,<br />

organismi allogeni,<br />

organismi <strong>in</strong>vasivi,<br />

biodiversità,<br />

neofite,<br />

animale <strong>in</strong>vasivi,<br />

piante <strong>in</strong>vasive

Vorwort 7<br />

> Vorwort<br />

Die weitgehend durch Klima und Geologie bestimmte Verteilung der Tier- und Pflanzenarten<br />

auf der Erde wurde lange Zeit durch natürliche Barrieren, wie Meere, Gebirge,<br />

Wüsten und Flüsse, aufrechterhalten. Mit der Überw<strong>in</strong>dung dieser Barrieren durch<br />

den Menschen ist, namentlich <strong>in</strong> den letzten hundert Jahren durch zunehmenden Handel<br />

und Tourismus, e<strong>in</strong>e neue Situation entstanden. Die Erde ist kle<strong>in</strong> geworden.<br />

Der Mensch reiste und reist aber nicht alle<strong>in</strong>e. Im «Gepäck» hat er – beabsichtigt oder<br />

unbeabsichtigt – Pflanzen- und Tierarten mitgeschleppt, von denen e<strong>in</strong>ige <strong>in</strong> der neuen<br />

Heimat zu massiven Problemen geführt haben. Bekannte Beispiele s<strong>in</strong>d die Ziegen auf<br />

den Galapagos- Inseln oder die Ratten und Katzen <strong>in</strong> Neuseeland, die zum Aussterben<br />

von Arten geführt haben, die e<strong>in</strong>malig auf der Welt waren.<br />

Im Gegensatz zu Inseln, die mit ihren spezifisch angepassten Arten e<strong>in</strong>zigartige Ökosysteme<br />

darstellen, ist Europa bislang weitgehend verschont geblieben von Problemen<br />

mit gebietsfremden Arten. Über die Ursachen wird spekuliert. Es kann daran liegen,<br />

dass Europa nie E<strong>in</strong>wanderungen erlebt hat wie Nord-Amerika oder Austr<strong>alien</strong>, wo die<br />

neuen Siedler mit ihren mitgebrachten Haustieren und Nutzpflanzen e<strong>in</strong>en massiven<br />

E<strong>in</strong>fluss auf die vorhandene Flora und Fauna ausgeübt haben. Vielleicht s<strong>in</strong>d aber auch<br />

unsere Ökosysteme robuster, so dass neue Arten es schwerer gehabt haben, Fuss zu<br />

fassen und die e<strong>in</strong>heimischen Arten zu verdrängen.<br />

Allerd<strong>in</strong>gs mehren sich auch <strong>in</strong> Europa und bei uns <strong>in</strong> der Schweiz heute die Anzeichen<br />

für Invasionen: Kanadische Goldrute, Riesenbärenklau und Ambrosia s<strong>in</strong>d Beispiele<br />

aus dem Pflanzenreich, die aktuell durch die Tagespresse gehen. Aus dem<br />

Tierreich s<strong>in</strong>d es das Grauhörnchen, die Schwarzkopfruderente oder der Amerikanische<br />

Flusskrebs, die den Naturschützern und Behörden zunehmend Kopfzerbrechen<br />

bereiten. Und selbst Insekten fallen vermehrt negativ auf, z.B. der Maiswurzelbohrer<br />

oder der Asiatische Marienkäfer, die unsere Nutzpflanzen direkt oder <strong>in</strong>direkt bedrohen.<br />

Die Folgen dieser Entwicklung s<strong>in</strong>d heute noch nicht abschätzbar.<br />

Nach der Biodiversitätskonvention ist die Schweiz verpflichtet, Massnahmen gegen<br />

<strong>in</strong>vasive gebietsfremde Arten zu ergreifen und deren Verbreitung e<strong>in</strong>zudämmen oder<br />

zu verh<strong>in</strong>dern. Nach dem Motto «Gefahr erkannt – Gefahr gebannt» ist es für die<br />

Schweiz von zentraler Bedeutung, potenziell gefährliche Arten zu erkennen. Das<br />

vorliegende Kompendium ist hierfür gedacht. Es beschreibt <strong>in</strong> umfassender Weise von<br />

den Flechten bis h<strong>in</strong> zu Säugetieren gebietsfremde Arten mit Schadenpotenzial, die<br />

schon hier s<strong>in</strong>d oder die vor den Toren der Schweiz stehen.<br />

Georg Karlaganis<br />

Head of Substances, Soil and Biotechnology Division<br />

Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN)

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> FOEN 2006 8<br />

> Summary<br />

Globalization is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g trade and travel on an unprecedented scale, and has <strong>in</strong>advertently<br />

led to the <strong>in</strong>creased transport and <strong>in</strong>troduction of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong>, break<strong>in</strong>g down<br />

the natural barriers between countries and cont<strong>in</strong>ents. Alien <strong>species</strong> are not bad per se,<br />

<strong>in</strong> fact many <strong>species</strong> are beneficial for humans, e.g. most crop <strong>species</strong>. However, some<br />

<strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> have become harmful, and pose threats to the environment and humans.<br />

<strong>Invasive</strong> <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> (IAS) are <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly recognized as one of the major threats to<br />

biodiversity.<br />

All signatories to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g <strong>Switzerland</strong>,<br />

have agreed to prevent the <strong>in</strong>troduction of, control or eradicate those <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong><br />

which threaten ecosystems, habitats or <strong>species</strong>.<br />

There is a widespread view that IAS are of less concern <strong>in</strong> Central Europe than on<br />

other cont<strong>in</strong>ents (and more especially on islands). Possible reasons for this <strong>in</strong>clude the<br />

small size of nature reserves, the high human impact on all ‘natural’ environments, and<br />

the long association of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and humans lead<strong>in</strong>g to familiarisation and adaptation.<br />

However, the number of cases of dramatic impact is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g and awareness<br />

among scientists and the public is steadily grow<strong>in</strong>g. Thus, the threats from IAS should<br />

not be underrated. One of the major consequences, which is undoubtedly unfold<strong>in</strong>g<br />

before our eyes, is global homogenization, with the unique character of places such as<br />

<strong>Switzerland</strong> be<strong>in</strong>g lost, the characteristic flora and fauna <strong>in</strong>vaded by organisms which<br />

reproduce to eventually form the largest proportion of biomass <strong>in</strong> certa<strong>in</strong> ecosystems.<br />

Time lags, i.e. the gap between establishment and <strong>in</strong>vasion, makes prediction of <strong>in</strong>vasiveness<br />

of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> very difficult. Well-established <strong>species</strong> show<strong>in</strong>g no h<strong>in</strong>t of any<br />

harm to the environment may still become <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>in</strong> the future. There are three major<br />

categories of factors that determ<strong>in</strong>e the ability of a <strong>species</strong> to become <strong>in</strong>vasive: <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sic<br />

factors or <strong>species</strong> traits; extr<strong>in</strong>sic factors or relationships between the <strong>species</strong> and<br />

abiotic and biotic factors; and the human dimension, <strong>in</strong>corporat<strong>in</strong>g the importance of<br />

<strong>species</strong> to humans.<br />

This report compiles <strong>in</strong>formation about <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> from published<br />

sources and experts <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> and abroad. Imm<strong>in</strong>ent future bio<strong>in</strong>vasions are also<br />

<strong>in</strong>cluded. The availability of national lists varies greatly between taxonomic groups.<br />

Thus, unfortunately, it is not possible to list all the <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> of <strong>Switzerland</strong>, s<strong>in</strong>ce<br />

not all resident <strong>species</strong> are known yet. However, for groups that are well known,<br />

complete lists have been compiled. For some groups only <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong> rather than<br />

<strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> are treated, and other groups could not be covered at all.<br />

The broad taxonomic group<strong>in</strong>gs used are vertebrates, crustaceans, <strong>in</strong>sects, arachnids,<br />

molluscs, other animals, fungi and plants. For each group, we present an overview, a<br />

list of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong>, Fact Sheets for the <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong>, an evaluation of the status,

Summary 9<br />

impacts, pathways and control options for the group, and recommendations. The Fact<br />

Sheets summarize <strong>in</strong>formation on the <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong> under the head<strong>in</strong>gs taxonomy,<br />

description, ecology, orig<strong>in</strong>, <strong>in</strong>troduction, distribution, impact, management and references.<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>itions of the important terms used <strong>in</strong> the report are given, s<strong>in</strong>ce frequently-used<br />

terms such as ‘<strong>in</strong>vasive’ are often used <strong>in</strong> different ways.<br />

The situation regard<strong>in</strong>g IAS <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> is similar to that <strong>in</strong> other Central European<br />

countries, <strong>in</strong> particular Austria, which is also a land-locked country conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g part of<br />

the Alps. This report lists about 800 <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and characterises 107 IAS <strong>in</strong> Fact<br />

Sheets: five mammals, four birds, one reptile, three amphibians, seven fish, four molluscs,<br />

16 <strong>in</strong>sects, six crustaceans, three spiders, two ‘worms’, seven fungi, one bacteria,<br />

and 48 plants.<br />

Pathways can be divided <strong>in</strong>to those for <strong>species</strong> deliberately <strong>in</strong>troduced and those for<br />

<strong>species</strong> accidentally <strong>in</strong>troduced. Pathways for deliberate <strong>in</strong>troductions <strong>in</strong>clude the trade<br />

of <strong>species</strong> used <strong>in</strong> aquaculture, for fisheries, as forest trees, for agricultural purposes,<br />

for hunt<strong>in</strong>g, for soil improvement and solely to please humans as ornamentals. Most of<br />

these can also transport hitchhik<strong>in</strong>g <strong>species</strong> and people can accidentally <strong>in</strong>troduce<br />

<strong>species</strong> while travell<strong>in</strong>g. In general, most aquatics and terrestrial <strong>in</strong>vertebratesand<br />

diseases are accidental arrivals, whereas most plants and vertebrates are deliberately<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced. The global trend for the latter groups also holds true for <strong>Switzerland</strong>, e.g.<br />

75 % of the 20 Black List plants were <strong>in</strong>troduced pr<strong>in</strong>cipally as ornamentals, and 35 of<br />

the 37 vertebrates were deliberately <strong>in</strong>troduced. Thus, many damag<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>vaders were<br />

deliberately <strong>in</strong>troduced, often with little justification beyond the wish to “improve” the<br />

landscape, e.g. ornamental plants and waterfowl.<br />

The impacts of IAS are often considerable, <strong>in</strong> particular when ecosystem function<strong>in</strong>g is<br />

altered or <strong>species</strong> are pushed to ext<strong>in</strong>ction, as has been shown for many bird <strong>species</strong> on<br />

islands. The environmental impacts can be divided <strong>in</strong>to four major factors: competition,<br />

predation, hybridization and transmission of diseases. The most obvious examples<br />

for competition are between <strong>in</strong>troduced and native plants for nutrients and exposure to<br />

sunlight. Resource competition has also led to the replacement of the native red squirrel<br />

(Sciurus vulgaris) by the <strong>in</strong>troduced American grey squirrel (S. carol<strong>in</strong>ensis) <strong>in</strong><br />

almost all of Great Brita<strong>in</strong> and it is predicted that this trend will cont<strong>in</strong>ue on the cont<strong>in</strong>ent.<br />

The musk rat (Ondatra zibethicus) causes decl<strong>in</strong>es of native mussels population<br />

(Unionidae) by predation and the amphipod Dikerogammarus villosus is a serious<br />

predator of native freshwater <strong>in</strong>vertebrates. A well-known example of hybridization<br />

from Europe is the ruddy duck (Oxyura jamaicensis), which hybridizes with the endangered<br />

native white-headed duck (O. leucocephala). In some cases IAS can harbour<br />

diseases and act as a vector for those diseases to native <strong>species</strong>. This is the case with<br />

American <strong>in</strong>troduced crayfish <strong>species</strong> to Europe, which are almost asymptomatic<br />

carriers of the <strong>alien</strong> crayfish plague (Aphanomyces astaci), but the native noble crayfish<br />

(Astacus astacus) is highly susceptible to the disease, and thus is struggl<strong>in</strong>g to<br />

coexist with populations of the American crayfish <strong>species</strong>.

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> FOEN 2006 10<br />

In addition to impacts on biodiversity, many IAS cause enormous economic costs.<br />

These costs can arise through direct losses of agricultural and forestry products and<br />

through <strong>in</strong>creased production costs associated with control measures. A North American<br />

study calculated costs of US$ 138 billion per annum to the USA from IAS. A<br />

recently released report estimates that weeds are cost<strong>in</strong>g agriculture <strong>in</strong> Australia about<br />

Aus$ 4 billion a year, whereas weed control <strong>in</strong> natural environments cost about Aus$<br />

20 million <strong>in</strong> the year from mid 2001 to mid 2002. In Europe, the costs of giant hogweed<br />

(Heracleum mantegazzianum) <strong>in</strong> Germany are estimated at € 10 million; € 1<br />

million relat<strong>in</strong>g to each of the environment and health sectors, and the rema<strong>in</strong>der<br />

represents costs to the agricultural and forestry sectors. Economic damage by the<br />

western corn rootworm (Diabrotica virgifera) is <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>g as it spreads through<br />

Europe. Some IAS also have implications for human health, e.g. giant hogweed produces<br />

copious amounts of a sap conta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g phototoxic substances (furanocoumar<strong>in</strong>s),<br />

which can lead to severe burns to the sk<strong>in</strong>. The raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides),<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced as a fur animal, can, like the native red fox (Vulpes vulpes), act as a<br />

vector of the most dangerous parasitic disease vectored by mammals to humans <strong>in</strong><br />

Central Europe, i.e. the fox tapeworm (Ech<strong>in</strong>ococcus multilocularis). Known impacts<br />

of <strong>species</strong> <strong>in</strong>troduced <strong>in</strong>to <strong>Switzerland</strong> are presented, although some recent <strong>in</strong>vaders<br />

have not yet been reported to have impact <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong>; <strong>in</strong> these cases impacts assessed<br />

<strong>in</strong> other countries are given. Demonstration of environmental impacts is often<br />

difficult because of the complexity of ecosystems, but <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> occurr<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> high<br />

numbers, such as Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica) totally cover<strong>in</strong>g riversides,<br />

or an animal biomass of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> of up to 95 % <strong>in</strong> the Rh<strong>in</strong>e near Basel, must have<br />

impacts on the native ecosystem. All <strong>species</strong> use resources and are resources to other<br />

creatures and so they alter the web and nutrient flow of the ecosystems they are liv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

<strong>in</strong>.<br />

Recommendations for the management – <strong>in</strong> its widest sense – of groups of <strong>in</strong>vasives<br />

and <strong>in</strong>dividual <strong>species</strong> are given <strong>in</strong> the respective chapters and Fact Sheets. Prepar<strong>in</strong>g a<br />

national strategy aga<strong>in</strong>st IAS is recommended to deal with IAS <strong>in</strong> an appropriate way<br />

and as anticipated by the CBD. This action plan should identify the agency responsible<br />

for assess<strong>in</strong>g the risks posed by <strong>in</strong>troductions, provide fund<strong>in</strong>g mechanisms and technical<br />

advice and support for control options. Prevention measures aga<strong>in</strong>st further bio<strong>in</strong>vasions<br />

need to be put <strong>in</strong> place to stem the tide of <strong>in</strong>com<strong>in</strong>g new <strong>species</strong> arriv<strong>in</strong>g<br />

accidentally with trade and travel or <strong>in</strong>troduced deliberately for various purposes. New<br />

deliberate <strong>in</strong>troductions must be assessed as to the threat they may present and only<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduced on the basis of a risk analysis and environmental impact assessment. This<br />

report <strong>in</strong>dicates some important pathways for consideration and shows that most<br />

<strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong> are deliberately <strong>in</strong>troduced. The use of native plants and non-<strong>in</strong>vasive<br />

<strong>alien</strong> plants for garden<strong>in</strong>g and other purposes should be promoted. Laws regulat<strong>in</strong>g<br />

trade <strong>in</strong> plant <strong>species</strong> on the Black List would be a first step <strong>in</strong> the right direction to<br />

reduce the impact of these <strong>species</strong>. However, restrictions for <strong>species</strong> already widely<br />

distributed with<strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> will not drastically change the situation unless the<br />

populations already present are eradicated or controlled. Fish <strong>in</strong>troductions are regulated<br />

by the Fisheries Act, which names those <strong>species</strong> for which an authorization for<br />

release is needed, and <strong>species</strong> for which release is prohibited altogether. This is a good<br />

basis, although the law could be better adapted to the current situation, as described <strong>in</strong>

Summary 11<br />

the fish section. The aquarium and terrarium trade is another important sector that<br />

could be more strictly regulated to stop releases of pets <strong>in</strong>to the wild. A major problem<br />

with <strong>in</strong>troductions of IAS is that the costs when they <strong>in</strong>vasive are borne by the public,<br />

while the f<strong>in</strong>ancial <strong>in</strong>centives for <strong>in</strong>troduc<strong>in</strong>g them lie with <strong>in</strong>dividuals or specific<br />

bus<strong>in</strong>esses. Development of economic tools that shift the burden of IAS to those who<br />

benefit from <strong>in</strong>ternational trade and travel is a neglected approach (also called the<br />

‘polluter pays’ pr<strong>in</strong>ciple). Appropriate tools would be fees and taxes, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g fees<br />

levied on those who import the organisms or goods. Awareness rais<strong>in</strong>g is a significant<br />

tool <strong>in</strong> the prevention and management of IAS, s<strong>in</strong>ce some member of the public would<br />

adhere to advice if they knew about its importance and the reason for it. Scientists and<br />

decision-makers also need better access to <strong>in</strong>formation about <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong>, their<br />

impacts, and management options. To address the impacts of those <strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>species</strong><br />

already present <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong>, their populations need to be managed: either eradicated<br />

or controlled. Possible targets for eradication are the sika deer (Cervus nippon), the<br />

mouflon (Ovis orientalis), and the ruddy shelduck (Tadorna ferrug<strong>in</strong>ea), which will<br />

otherwise <strong>in</strong>crease its range and spread to neighbour<strong>in</strong>g countries. A pilot national<br />

eradication / control programme aga<strong>in</strong>st a prom<strong>in</strong>ent <strong>in</strong>vader, e.g. a Black List plant<br />

<strong>species</strong>, is recommended as a case study. Monitor<strong>in</strong>g populations of some <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong><br />

is recommended to detect any sudden <strong>in</strong>creases <strong>in</strong>dicat<strong>in</strong>g potential <strong>in</strong>vasiveness. By<br />

do<strong>in</strong>g this, control or even eradication efforts can be employed before the populations<br />

become unmanageable. While compil<strong>in</strong>g the <strong>in</strong>formation for this report it became clear<br />

that more <strong>in</strong>formation about the status of IAS <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> is needed. More studies<br />

on <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> are highly recommended to assess the importance of IAS and to demonstrate<br />

their significance to policy-makers and politicians.<br />

Limited resources dictate the need for sett<strong>in</strong>g priorities and allocat<strong>in</strong>g funds where it<br />

will have the greatest impact <strong>in</strong> combat<strong>in</strong>g IAS. Important po<strong>in</strong>ts, for example, are to<br />

critically assess the feasibility of different approaches, and to target <strong>species</strong> for which<br />

there is no conflict of <strong>in</strong>terest. Opposition to action aga<strong>in</strong>st less-important ornamentals<br />

on the Black List and <strong>species</strong> of direct human health concern (giant hogweed) should<br />

be negligible.

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> FOEN 2006 12<br />

> Zusammenfassung<br />

Mit der zunehmenden Globilisierung ist e<strong>in</strong> starker Anstieg des Warentransportes,<br />

Verkehrs und Tourismus zu verzeichnen. Dies führt zu ungewollten wie beabsichtigten<br />

E<strong>in</strong>führungen von gebietsfremden Arten <strong>in</strong> e<strong>in</strong>em noch nie dagewesenen Umfang, und<br />

der Verschmelzung von Biodiversitäten der unterschiedlichen Länder und Kont<strong>in</strong>ente,<br />

so dass nur schwer zu überbrückende natürliche Ausbreitungsschranken plötzlich<br />

überwunden werden. Nicht alle gebietsfremden Arten s<strong>in</strong>d automatisch als negativ zu<br />

bewerten. Tatsächlich s<strong>in</strong>d viele Arten wichtige Bestandteile der Ökonomie e<strong>in</strong>es<br />

Landes, man denke nur an die zahlreichen gebietsfremden Kulturpflanzen. E<strong>in</strong>ige<br />

Arten entwickeln sich allerd<strong>in</strong>gs zu Problemarten und bedrohen die e<strong>in</strong>heimische<br />

Biodiversität, richten wirtschaftlichen Schaden an oder stellen e<strong>in</strong>e Gefahr für die<br />

Gesundheit dar.<br />

Gebietsfremde Problemarten (<strong>in</strong>vasive <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong>) werden heute als e<strong>in</strong>e Hauptbedrohung<br />

für die Biodiversität angesehen. Die Biodiversitätskonvention (CBD) verpflichtet<br />

die <strong>in</strong>ternationale Staatengeme<strong>in</strong>schaft Vorsorge gegen diese <strong>in</strong>vasiven Arten<br />

zu treffen und diese gegebenenfalls zu bekämpfen.<br />

Gebietsfremde Arten <strong>in</strong> Zentraleuropa werden oft als ger<strong>in</strong>ges Problem e<strong>in</strong>gestuft, im<br />

Vergleich zu anderen Kont<strong>in</strong>enten und vor allem Inseln. Mögliche Gründe für diese<br />

Unterschiede s<strong>in</strong>d die relativ kle<strong>in</strong>en Schutzgebiete, was die Möglichkeit für e<strong>in</strong>e<br />

<strong>in</strong>tensive Pflege eröffnet, die stark vom Menschen bee<strong>in</strong>flussten ‘Naturräume’ und das<br />

lange Zusammenleben von vielen gebietsfremden Arten mit dem Menschen, das zu<br />

vielfältigen Anpassungen geführt hat. Trotzdem nehmen die Fälle von dramatischen<br />

Auswirkungen von gebietsfremden Arten und das Bewusstse<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> der Bevölkerung und<br />

bei den Wissenschaftlern zu. Zweifellos ist die globale Homogenisierung <strong>in</strong> vollem<br />

Gange und der e<strong>in</strong>zigartige Charakter von lokalen Ökosystemen, wie zum Beispiel <strong>in</strong><br />

der Schweiz, gehen für immer verloren, da die charakteristische Pflanzen- und Tierwelt<br />

von gebietsfremden Arten verändert wird und e<strong>in</strong>ige dieser Arten die grössten Anteile<br />

an der Biomasse von e<strong>in</strong>igen Ökosystemen erreichen.<br />

Die Zeitdifferenz, die zwischen der Ankunft e<strong>in</strong>er Art und ihrer starken Ausbreitung<br />

auftreten kann, macht Voraussagungen der Invasivität von Arten aussserordentlich<br />

schwierig. E<strong>in</strong>ige schon lange etablierte Arten können plötzlich und unerwartet <strong>in</strong>vasiv<br />

werden. Drei Kategorien von Faktoren bestimmen die Invasivität von Arten: 1. die<br />

biologischen Merkmale e<strong>in</strong>er Art, 2. das Zusammenspiel e<strong>in</strong>er Art mit ihrer abiotischen<br />

und biotischen Umwelt und 3. die Beziehungen der Menschen zu dieser Art.<br />

In diesem Bericht ist Information über gebietsfremde Arten der Schweiz sowohl von<br />

publizierten Dokumenten als auch von direktem Austausch mit Experten <strong>in</strong> der<br />

Schweiz und des Auslandes zusammengetragen. Bevorstehende E<strong>in</strong>wanderungen s<strong>in</strong>d<br />

ebenfalls erfasst worden. Die Verfügbarkeit von Artenlisten <strong>in</strong> den e<strong>in</strong>zelnen taxonomischen<br />

Gruppen ist sehr unterschiedlich, so dass es nicht möglich ist alle gebiets-

Zusammenfassung 13<br />

fremden Arten zu benennen. In e<strong>in</strong>igen Gruppen ist das Wissen sogar der e<strong>in</strong>heimische<br />

Arten so rudimentär, dass ke<strong>in</strong> Versuch gemacht wurde, sie zu bearbeiten, und bei<br />

anderen Gruppen wurden nur Problemarten aufgenommen. Die Listen der gebietsfremden<br />

Arten wieder anderer Gruppen dagegen s<strong>in</strong>d vollständig.<br />

Die gebietsfremden Organismen wurden <strong>in</strong> folgende Gruppen aufgeteilt: Wirbeltiere,<br />

Krebstiere, Insekten, Sp<strong>in</strong>nentiere, Weichtiere, andere Tiere, Pilze und Pflanzen. In<br />

jedem Kapitel bef<strong>in</strong>den sich die Listen der gebietsfremden Arten, e<strong>in</strong> erläuternder Text,<br />

Datenblätter der Problemarten und e<strong>in</strong>e Auswertung der Situation, der negativen<br />

Auswirkungen, der E<strong>in</strong>führungswege, der möglichen Gegensteuerungsmassnahmen<br />

und Empfehlungen für den Umgang mit diesen Arten. Die Datenblätter bieten Information<br />

zu Taxonomie, Beschreibung, Ökologie, Herkunft, E<strong>in</strong>führungswege, Verbreitung,<br />

Auswirkungen, Ansätze zur Gegensteuerung und e<strong>in</strong> Literaturverzeichnis.<br />

Def<strong>in</strong>itionen der wichtigsten Begriffe, wie sie <strong>in</strong> diesem Dokument benutzt werden,<br />

werden ebenfalls gegeben, da sie oftmals unterschiedlich gebraucht werden.<br />

Die Situation der gebietsfremden Arten der Schweiz ist ähnlich wie <strong>in</strong> anderen mitteleuropäischen<br />

Ländern, vor allem Österreich, das e<strong>in</strong>e ähnliche Topographie besitzt.<br />

Dieser Bericht über die gebietsfremden Arten der Schweiz listet über 800 etablierte<br />

gebietsfremde Arten auf und stellt die 107 Problemarten <strong>in</strong> Datenblättern vor: fünf<br />

Säugetiere, vier Vögel, e<strong>in</strong> Reptil, drei Amphibien, sieben Fische, vier Weichtiere, 16<br />

Insekten, sechs Krebstiere, drei Sp<strong>in</strong>nen, zwei ‘Würmer’, sieben Pilze, e<strong>in</strong> Bakterium<br />

und 48 Pflanzen.<br />

Es können versehentlich e<strong>in</strong>geschleppte Arten und bewusst e<strong>in</strong>geführte Arten unterschieden<br />

werden. E<strong>in</strong>geführt s<strong>in</strong>d zum Beispiel Arten der Aquakulturen, der Fischerei,<br />

der Waldwirtschaft, der Landwirtschaft, der Jagd, zur Bodenverbesserung und e<strong>in</strong>fach<br />

zur Bereicherung der Landschaft, wie Zierpflanzen. Viele der e<strong>in</strong>geführten Arten<br />

können allerd<strong>in</strong>gs andere Arten auf und <strong>in</strong> sich tragen und so e<strong>in</strong>schleppen, und der<br />

reisende Mensch transportiert ebenfalls oftmals gebietsfremde Arten. Die meisten<br />

aquatischen und terrestrischen Wirbellosen und Krankheiten wurden versehentlich<br />

e<strong>in</strong>geschleppt, während Pflanzen und Wirbeltiere meist e<strong>in</strong>geführt worden s<strong>in</strong>d. Dieser<br />

globale Trend f<strong>in</strong>det sich auch bei den gebietsfremden Arten der Schweiz wieder, denn<br />

75 % der 20 Arten auf der ‘Schwarzen Liste’ wurden als Zierpflanzen e<strong>in</strong>geführt und<br />

35 der 37 Wirbeltiere wurde zu e<strong>in</strong>em bestimmten Zweck importiert. Das heisst, dass<br />

viele der Problemarten bewusst e<strong>in</strong>geführt wurden, oftmals mit e<strong>in</strong>er ger<strong>in</strong>gfügigen<br />

Rechtfertigung, z.B. um die Landschaft mit Zierpflanzen und Wasservögeln zu ‘bereichern’.<br />

Die Auswirkungen, die gebietsfremde Arten auslösen können, s<strong>in</strong>d oft beträchtlich, vor<br />

allem wenn die Funktion e<strong>in</strong>es Ökosystems gestört wird, e<strong>in</strong>heimische Arten verdrängt<br />

werden oder sogar aussterben, wie es bei Vogelarten auf Inseln dokumentiert worden<br />

ist. Vier Faktoren können zu solchen Problemen führen: 1. Konkurrenz zu e<strong>in</strong>heimischen<br />

Arten, 2. e<strong>in</strong> gebietsfremder Räuber, 3. die Hybridisierung mit e<strong>in</strong>heimischen<br />

Arten und 4. die Ausbreitung von Krankheiten durch e<strong>in</strong>en gebietsfremden Vektor.<br />

Offensichtliche Beispiele für Konkurrenz s<strong>in</strong>d der Kampf um Licht und Nährstoffe

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> FOEN 2006 14<br />

zwischen gebietsfremden und e<strong>in</strong>heimischen Pflanzenarten. Der Konkurrenzkampf um<br />

Nahrung hat <strong>in</strong> Grossbrittanien zur fast völligen Verdrängung des Eichhörnchens<br />

(Sciurus vulgaris) durch das e<strong>in</strong>geführte Grauhörnchen (S. carol<strong>in</strong>ensis) geführt und es<br />

ist zu befürchten, dass dieser Trend auch auf dem Festland weitergehen wird. Der<br />

Bisam (Ondatra zibethicus) hat als Räuber der e<strong>in</strong>heimischen Muscheln (Unionidae)<br />

zu ihrem Rückgang beigetragen und der Amphipode Dikerogammarus villosus ist e<strong>in</strong><br />

grosser Fe<strong>in</strong>d der e<strong>in</strong>heimischen Wirbellosen der Gewässer. E<strong>in</strong> bekanntes Beispiel für<br />

e<strong>in</strong>e Hybridisierung ist die e<strong>in</strong>geführte Schwarzkopf-Ruderente (Oxyura jamaicensis),<br />

die sich mit der stark gefährdeten Weisskopf-Ruderente (O. leucocephala) verpaart. In<br />

e<strong>in</strong>igen Fällen können gebietsfremde Arten Krankheiten unter e<strong>in</strong>heimischen Arten<br />

verbreiten. Dies ist der Fall bei der berüchtigten Krebspest (Aphanomyces astaci), die<br />

von ebenfalls e<strong>in</strong>geführten nordamerikanischen Flusskrebsen, die fast ke<strong>in</strong>e Symptome<br />

zeigen, auf den e<strong>in</strong>heimischen Flusskrebs (Astacus astacus), der dramatisch mit e<strong>in</strong>em<br />

sofortigen Zusammenbruch der Population reagiert, übertragen werden.<br />

Neben diesen Auswirkungen auf die Umwelt, können gebietsfremde Arten auch enorme<br />

ökonomische Schäden verursachen. Die Kosten können durch den Verlust von<br />

land- und forstwirtschaftlichen Produkten und durch erhöhte Produktionskosten durch<br />

Bekämpfungsmassnahmen entstehen. E<strong>in</strong>e nordamerikanische Studie hat die jährlichen<br />

Kosten von gebietsfremden Arten <strong>in</strong> der USA auf 13,8 Milliarden US Dollar berechnet.<br />

E<strong>in</strong> anderer Bericht schätzt die Kosten durch Unkräuter für die australische Landwirtschaft<br />

auf 4 Milliarden Australische Dollar, und 20 Millionen Aus. $ wurden während<br />

e<strong>in</strong>es Jahres zwischen Mitte 2001 und Mitte 2002 für die Unkrautbekämpfung auf<br />

naturnahen Flächen ausgegeben. Die Kosten durch den Riesenbärenklau (Heracleum<br />

mantegazzianum) <strong>in</strong> Deutschland werden auf 10 Millionen € geschätzt, wobei je e<strong>in</strong>e<br />

Millionen im Umweltbereich und Gesundheitswesen anfallen und der Rest <strong>in</strong> Landwirtschaft<br />

und Forst. Der Westliche Maiswurzelbohrer (Diabrotica virgifera) dehnt<br />

se<strong>in</strong>e Verbreitung weiter nach Nordwesten aus und bereitet grosse Schäden an den<br />

Maiskulturen. E<strong>in</strong>ige gebietsfremde Arten schaden der menschlichen Gesundheit, so<br />

produziert der Riesenbärenklau grosse Mengen e<strong>in</strong>es Saftes der phototoxische Substanzen<br />

(Furanocumar<strong>in</strong>e), die zu starken Verbrennungen der Haut führen können,<br />

enthält. Der Marderhund (Nyctereutes procyonoides), als Pelztier e<strong>in</strong>geführt, kann, wie<br />

der e<strong>in</strong>heimische Rotfuchs (Vulpes vulpes), als Vektor des Fuchsbandwurmes (Ech<strong>in</strong>ococcus<br />

multilocularis), der gefährlichsten Krankheit, die <strong>in</strong> Zentraleuropa von Säugetieren<br />

auf den Menschen übertragen wird, fungieren. Für diesem Bericht wurden<br />

bekannte Auswirkungen von gebietsfremden Arten <strong>in</strong> der Schweiz zusammengetragen.<br />

Für Arten, die noch nicht lange <strong>in</strong> der Schweiz vorkommen, wurde auf Berichten von<br />

Auswirkungen <strong>in</strong> anderen Ländern zurückgegriffen. Es muss erwähnt werden, dass<br />

Nachweise von Auswirkungen e<strong>in</strong>er gebietsfremden Art <strong>in</strong> e<strong>in</strong>em komplexen Ökosystem<br />

oft schwierig zu führen s<strong>in</strong>d. Andererseits ist es offensichtlich, dass Arten wie der<br />

Japanische Staudenknöterich (Reynoutria japonica), der oft ganze Flussufer säumt,<br />

oder e<strong>in</strong>e tierische Biomasse von gebietsfremden Arten von 95 % im Rhe<strong>in</strong> bei Basel,<br />

e<strong>in</strong>e Auswirkung auf das Ökosystem haben müssen. Alle Arten verbrauchen Nährstoffe<br />

und dienen als Nährstoff für andere Organismen und ändern so das Nahrungsnetz und<br />

den Nährstofffluss der Ökosysteme, die sie besiedeln.

Zusammenfassung 15<br />

In den Texten der jeweiligen Kapitel und den Datenblättern s<strong>in</strong>d Empfehlungen zur<br />

Gegensteuerung (Prävention und Kontrolle) für die Gruppen und e<strong>in</strong>zelnen Arten<br />

gegeben. Allgeme<strong>in</strong> ist die Erstellung e<strong>in</strong>er Nationalen Strategie im H<strong>in</strong>blick auf<br />

gebietsfremde Arten zu empfehlen, um angemessene Schritte ergreifen zu können, und<br />

es von der Biodiversitätskonvention gefordert ist. Dieser Plan sollte e<strong>in</strong>e zuständige<br />

Behörde identifizieren, die die Risiken von E<strong>in</strong>führungen und E<strong>in</strong>schleppungen beurteilt,<br />

für f<strong>in</strong>anzielle Mittel sorgt und technische Unterstützung zur Bekämpfung bereitstellt.<br />

Massnahmen zur Prävention um weitere Bio<strong>in</strong>vasionen zu stoppen oder zu<br />

verm<strong>in</strong>dern müssen ausgearbeitet werden. E<strong>in</strong>führungen von neuen Organismen sollten<br />

vorher auf ihre möglichen Gefahren für die Umwelt untersucht werden und nur auf der<br />

Basis e<strong>in</strong>er Risikoanalyse e<strong>in</strong>geführt werden. Die Analyse der wichtigsten E<strong>in</strong>führungswege<br />

zeigt unmissverständlich, dass die meisten Problemarten bewusst e<strong>in</strong>geführt<br />

wurden (und werden). Die Nutzung von e<strong>in</strong>heimischen Arten und fremden Arten ohne<br />

Potential zur Invasivität zum Beispiel <strong>in</strong> Gärten, Parks und Forsten sollte mehr gefördert<br />

werden. Gesetze, die den Handel mit Pflanzenarten der ‘Schwarzen Liste’ regeln,<br />

wären e<strong>in</strong> konsequenter nächster Schritt, um die Auswirkungen dieser Arten zu reduzieren.<br />

Wenn die Arten allerd<strong>in</strong>gs schon e<strong>in</strong>e weite Verbreitung <strong>in</strong> der Schweiz besitzen,<br />

können nur Kontrollmassnahmen oder e<strong>in</strong>e erfolgreiche Ausrottung Abhilfe<br />

schaffen. Die Fischereiverordnung reguliert Fischaussetzungen, <strong>in</strong>dem sie Arten benennt<br />

für die e<strong>in</strong>e Bewilligung nötig ist und Arten, deren Aussetzung verboten ist.<br />

Diese solide Basis könnte noch verbessert werden, um der Situation besser zu entsprechen,<br />

wie <strong>in</strong> dem Teil über Fische beschrieben. E<strong>in</strong> weiterer Sektor, der mehr reguliert<br />

werden sollte, ist der Handel mit Haustieren (vor allem Aquarium and Terrarium), der<br />

immer wieder zu Aussetzungen führt. E<strong>in</strong> Grundproblem der E<strong>in</strong>führungen ist, dass die<br />

Kosten von Problemarten von der Öffentlichkeit getragen werden, während der f<strong>in</strong>anzielle<br />

Nutzen der E<strong>in</strong>führung e<strong>in</strong>zelnen Importeuren oder bestimmten Wirtschaftszweigen<br />

zugute kommt. Die Entwicklung von ökonomischen Programmen, die die Last<br />

auf die verteilt, die auch den Nutzen aus der E<strong>in</strong>fuhr haben, ist e<strong>in</strong> vernachlässigter<br />

Denkansatz (Verursacherpr<strong>in</strong>zip genannt). Möglichkeiten wären gegeben durch die<br />

Erhebung von Gebühren und Steuern, die für den Importeur zu bezahahlen wären. E<strong>in</strong>e<br />

wichtige Vorgehensweise, um die Probleme mit gebietsfremden Arten unter Kontrolle<br />

zu kriegen, ist die Schaffung e<strong>in</strong>es geschärftes Bewusstse<strong>in</strong>s der Problematik <strong>in</strong> der<br />

Bevölkerung. Wissenschaftler und Entscheidungsträger benötigen ebenfalls mehr<br />

Information über gebietsfremde Problemarten, deren Auswirkungen und den Möglichkeiten<br />

für e<strong>in</strong>e Gegensteuerung. E<strong>in</strong>ige Problemarten müssten bekämpft oder ausgerottet<br />

werde, um ihre Auswirkungen wirkungsvoll zu m<strong>in</strong>imieren. Mögliche Zielarten für<br />

e<strong>in</strong>e Ausrottung s<strong>in</strong>d der Sikahirsch (Cervus nippon), das Mufflon (Ovis orientalis)<br />

oder die Rostgans (Tadorna ferrug<strong>in</strong>ea), die sonst ihre Verbreitung weiter ausdehnt<br />

und die Nachbarländer erreichen wird. Für e<strong>in</strong>e erste grossangelegte Ausrottung oder<br />

Bekämpfung ist ebenfalls e<strong>in</strong>e Pflanzenart der ‘Schwarzen Liste’ zu empfehlen. Ausserdem<br />

wäre die Beobachtung der Populationen von gebietsfremden Arten empfehlenswert,<br />

um etwaige starke Zunahmen früh zu erkennen. In diesem Fall könnten<br />

Gegenmassnahmen ergriffen werden, bevor die Populationen zu gross werden. Beim<br />

Zusammentragen der Informationen wurde schnell klar, dass viel mehr Information<br />

über gebietsfremde Arten benotigt wird. Daher s<strong>in</strong>d mehr Studien zur Bedeutung von<br />

gebietsfremden Arten nötig, um Entscheidungsträger und Politiker auf die Lage aufmerksam<br />

zu machen.

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> FOEN 2006 16<br />

Die limitierten Ressourcen, die zur Verfügung stehen, zw<strong>in</strong>gen Prioritäten zu setzen,<br />

um die f<strong>in</strong>anziellen Mittel dort e<strong>in</strong>zusetzen, wo sie die meiste Wirkung zeigen im<br />

Kampf gegen Problemarten. Dabei müssen wichtige Punkte berücksichtigt werden,<br />

etwa, welche Methode den grössten Nutzen br<strong>in</strong>gt, oder welche Arten für Bekämpfungsmassnahmen<br />

zuerst <strong>in</strong> Betracht gezogen werden sollten. Arten mit e<strong>in</strong>em hohen<br />

Potenzial für Konflikte versprechen weniger Erfolg. Wenn Arten der ‘Schwarzen<br />

Liste’, welche ke<strong>in</strong>e grosse Wichtigkeit als Zierpflanzen besitzen, oder Arten die den<br />

Menschen gefährden, als Ziele ausgewählt werden, ist der zu erwartende Widerstand<br />

gegen Massnahmen eher ger<strong>in</strong>g e<strong>in</strong>zuschätzen.

Résumé 17<br />

> Résumé<br />

La globalisation a pour effet une augmentation sans précédant du commerce et des<br />

transports, dont une des conséquences est l’accroissement des déplacements et <strong>in</strong>troductions<br />

d’espèces exotiques. Les espèces exotiques ne sont pas toutes nuisibles. En<br />

fait un grande nombre d’entre elles sont bénéfiques, comme par exemple les nombreuses<br />

plantes cultivées d’orig<strong>in</strong>e étrangère. Cependant, certa<strong>in</strong>es espèces exotiques deviennent<br />

nuisibles et posent des problèmes à l’environnement et à l’homme en général.<br />

Les Espèces Exotiques Envahissantes (EEE) sont de plus en plus reconnues comme<br />

une des menaces les plus sérieuses posées à la biodiversité.<br />

Tous les pays signataires de la convention sur la diversité biologique (CDB), dont la<br />

Suisse, se sont engagés à prévenir l’<strong>in</strong>troduction, à contrôler ou éradiquer les espèces<br />

exotiques menaçant les écosystèmes, les habitats ou les espèces.<br />

Il est communément avancé que les EEE causent mo<strong>in</strong>s de problèmes en Europe<br />

Centrale que dans d’autres cont<strong>in</strong>ents ou régions. Les raisons possibles sont, entre<br />

autres, la taille limitée des réserves naturelles, l’impact huma<strong>in</strong> important dans tous les<br />

milieux « naturels » et la longue association, en Europe, entre les espèces exotiques et<br />

l’homme, ayant conduit à une familiarisation de ces espèces et une adaptation à<br />

l’environnement huma<strong>in</strong>. Cependant, le nombre de cas d’espèces exotiques causant des<br />

dégâts importants est en augmentation en Europe, un phénomène dont les chercheurs,<br />

mais également le public, ont de plus en plus conscience. De fait, la menace des espèces<br />

envahissantes ne doit pas être sous-estimée. Une des conséquences les plus visibles<br />

est le phénomène d’uniformisation, menant à la perte de paysages uniques, y compris<br />

en Suisse. La flore et la faune caractéristiques sont de plus en plus envahies par les<br />

organismes exotiques qui se reproduisent, pour f<strong>in</strong>alement composer la plus grande<br />

partie de la biomasse de certa<strong>in</strong>s écosystèmes.<br />

Le délai qui s’écoule entre la phase d’établissement et d’<strong>in</strong>vasion d’une espèce exotique<br />

(‘time lag’), rend la prédiction du phénomène d’<strong>in</strong>vasion très difficile. Des espèces<br />

bien établies qui n’ont actuellement aucun impact reconnu sur l’environnement peuvent<br />

malgré tout devenir envahissantes dans le futur. Trois catégories de facteurs<br />

déterm<strong>in</strong>ent la capacité d’une espèce à devenir envahissante: les facteurs <strong>in</strong>tr<strong>in</strong>sèques<br />

liés à l’espèce, les facteurs extr<strong>in</strong>sèques, c.-à-d. les relations entre l’espèce et les facteurs<br />

biotiques ou abiotiques, et la dimension huma<strong>in</strong>e, par exemple l’importance de<br />

l’espèce pour l’homme.<br />

Ce rapport est une compilation des connaissances sur les espèces exotiques en Suisse,<br />

rassemblées à partir de publications et d’avis d’experts suisses et étrangers. Des <strong>in</strong>formations<br />

sur les <strong>in</strong>vasions biologiques imm<strong>in</strong>entes sont également <strong>in</strong>clues. La connaissance<br />

des espèces présentes en Suisse variant fortement d’un groupe taxonomique à<br />

l’autre (pour certa<strong>in</strong>s taxa, même les espèces <strong>in</strong>digènes sont lo<strong>in</strong> d’être toutes connues),<br />

il n’a malheureusement pas été possible d’établir une liste exhaustive d’espèces exoti-

An <strong>in</strong>ventory of <strong>alien</strong> <strong>species</strong> and their threat to biodiversity and economy <strong>in</strong> <strong>Switzerland</strong> FOEN 2006 18<br />

ques pour tous les groupes. Une liste complète a été établie seulement pour les groupes<br />

taxonomiques bien connus. Pour certa<strong>in</strong>s groupes, seules les espèces envahissantes ont<br />

été compilées alors que quelques groupes n’ont pas pu être traités.<br />

Les grands groupes taxonomiques traités sont les vertébrés, les crustacés, les <strong>in</strong>sectes,<br />

les arachnides, les mollusques, les autres animaux, les champignons et les plantes. Pour<br />

chaque groupe, nous présentons une discussion générale, la liste des espèces non<strong>in</strong>digènes,<br />

les fiches d’<strong>in</strong>formation sur les espèces envahissantes et une évaluation du<br />

statut, de l’impact, des modes d’<strong>in</strong>troduction, les méthodes de lutte et des recommandations<br />

générales. Les fiches d’<strong>in</strong>formation résument, pour des espèces particulièrement<br />

envahissantes ou potentiellement dangereuses, les <strong>in</strong>formations sur la taxonomie, la<br />

description, l’écologie, l’orig<strong>in</strong>e, l’<strong>in</strong>troduction en Suisse et en Europe, la distribution,<br />

l’impact, la gestion et les références bibliographiques.<br />

Les déf<strong>in</strong>itions des termes anglais les plus importants utilisés dans ce rapport sont<br />

données, parce que les mots fréquemment utilisés comme « <strong>in</strong>vasive » sont parfois<br />

utilisés dans des sens différents.<br />

La situation concernant les EEE en Suisse est similaire à celle d’autres pays d’Europe<br />

Centrale, en particulier l’Autriche, un pays également enclavé et Alp<strong>in</strong>. Ce rapport<br />

<strong>in</strong>ventorie environ 800 espèces non-<strong>in</strong>digènes et détaille 107 espèces envahissantes<br />

sous forme de fiches d’<strong>in</strong>formation : c<strong>in</strong>q mammifères, quatre oiseaux, un reptile, trois<br />

amphibiens, sept poissons, quatre mollusques, 16 <strong>in</strong>sectes, six crustacés, trois araignées,<br />

deux « vers », sept champignons, une bactérie et 48 plantes.<br />

Les modes d’<strong>in</strong>troduction des espèces exotiques sont différents selon qu’il s’agit<br />

d’espèces délibérément <strong>in</strong>troduites ou d’espèces <strong>in</strong>troduites accidentellement. Les<br />

<strong>in</strong>troductions délibérées concernent pr<strong>in</strong>cipalement les espèces importées pour l’aquaculture,<br />

la pêche, la chasse, la sylviculture, l’agriculture, l’horticulture et la protection<br />

des sols. Les organismes <strong>in</strong>troduits <strong>in</strong>volontairement sont souvent transportés par<br />

<strong>in</strong>advertance avec d’autres importations ou par des voyageurs. En général, la plupart<br />

des <strong>in</strong>vertébrés et des pathogènes ont été <strong>in</strong>troduits accidentellement, alors que les<br />

plantes et les vertébrés l’ont souvent été <strong>in</strong>tentionnellement. Cette tendance est également<br />

valable pour la Suisse. Sur les 20 plantes envahissantes de la liste noire, 75 % ont<br />

été <strong>in</strong>troduites pr<strong>in</strong>cipalement en tant que plantes ornementales et 35 des 37 vertébrés<br />

exotiques établis en Suisse ont été <strong>in</strong>troduits délibérément. Il est donc important de<br />

constater que beaucoup d’envahisseurs, dont certa<strong>in</strong>s parmi les plus nuisibles, ont été<br />

<strong>in</strong>troduits <strong>in</strong>tentionnellement, souvent sans autre soucis que d’améliorer le paysage,<br />

comme c’est le cas pour les plantes et animaux d’ornement.<br />

L’impact des EEE est parfois considérable, en particulier quand l’envahisseur altère le<br />

fonctionnement d’un écosystème ou pousse les espèces <strong>in</strong>digènes vers l’ext<strong>in</strong>ction,<br />

comme cela a été souvent observé avec les oiseaux en milieu <strong>in</strong>sulaire. Les impacts<br />

écologiques peuvent être causés par quatre mécanismes majeurs : la compétition, la<br />

prédation, l’hybridation et la transmission de maladies. Parmi les exemples les plus<br />

significatifs de compétition, nous pouvons citer la compétition entre les plantes <strong>in</strong>digènes<br />

et exotiques pour les nutriments et la lumière. La compétition pour les ressources a

Résumé 19<br />

également conduit au remplacement de l’écureuil roux <strong>in</strong>digène (Sciurus vulgaris) par<br />

l’écureuil gris américa<strong>in</strong> (S. carol<strong>in</strong>ensis) dans la plus grande partie de la Grande-<br />