UNDERSTANDING VARIATION IN PARTITION COEFFICIENT, Kd ...

UNDERSTANDING VARIATION IN PARTITION COEFFICIENT, Kd ...

UNDERSTANDING VARIATION IN PARTITION COEFFICIENT, Kd ...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

United States Office of Air and Radiation EPA 402-R-99-004B<br />

Environmental Protection August 1999<br />

Agency<br />

<strong>UNDERSTAND<strong>IN</strong>G</strong> <strong>VARIATION</strong> <strong>IN</strong><br />

<strong>PARTITION</strong> <strong>COEFFICIENT</strong>, K d, VALUES<br />

Volume II:<br />

Review of Geochemistry and Available K d Values<br />

for Cadmium, Cesium, Chromium, Lead, Plutonium,<br />

Radon, Strontium, Thorium, Tritium ( 3 H), and Uranium

<strong>UNDERSTAND<strong>IN</strong>G</strong> <strong>VARIATION</strong> <strong>IN</strong><br />

<strong>PARTITION</strong> <strong>COEFFICIENT</strong>, K d, VALUES<br />

Volume II:<br />

Review of Geochemistry and Available K d Values<br />

for Cadmium, Cesium, Chromium, Lead, Plutonium,<br />

Radon, Strontium, Thorium, Tritium ( 3 H), and Uranium<br />

August 1999<br />

A Cooperative Effort By:<br />

Office of Radiation and Indoor Air<br />

Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response<br />

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency<br />

Washington, DC 20460<br />

Office of Environmental Restoration<br />

U.S. Department of Energy<br />

Washington, DC 20585

NOTICE<br />

The following two-volume report is intended solely as guidance to EPA and other<br />

environmental professionals. This document does not constitute rulemaking by the Agency, and<br />

cannot be relied on to create a substantive or procedural right enforceable by any party in<br />

litigation with the United States. EPA may take action that is at variance with the information,<br />

policies, and procedures in this document and may change them at any time without public notice.<br />

Reference herein to any specific commercial products, process, or service by trade name,<br />

trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement,<br />

recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government.<br />

ii

FOREWORD<br />

Understanding the long-term behavior of contaminants in the subsurface is becoming<br />

increasingly more important as the nation addresses groundwater contamination. Groundwater<br />

contamination is a national concern as about 50 percent of the United States population receives<br />

its drinking water from groundwater. It is the goal of the Environmental Protection Agency<br />

(EPA) to prevent adverse effects to human health and the environment and to protect the<br />

environmental integrity of the nation’s groundwater.<br />

Once groundwater is contaminated, it is important to understand how the contaminant<br />

moves in the subsurface environment. Proper understanding of the contaminant fate and transport<br />

is necessary in order to characterize the risks associated with the contamination and to develop,<br />

when necessary, emergency or remedial action plans. The parameter known as the partition (or<br />

distribution) coefficient (K d) is one of the most important parameters used in estimating the<br />

migration potential of contaminants present in aqueous solutions in contact with surface,<br />

subsurface and suspended solids.<br />

This two-volume report describes: (1) the conceptualization, measurement, and use of the<br />

partition coefficient parameter; and (2) the geochemical aqueous solution and sorbent properties<br />

that are most important in controlling adsorption/retardation behavior of selected contaminants.<br />

Volume I of this document focuses on providing EPA and other environmental remediation<br />

professionals with a reasoned and documented discussion of the major issues related to the<br />

selection and measurement of the partition coefficient for a select group of contaminants. The<br />

selected contaminants investigated in this two-volume document include: chromium, cadmium,<br />

cesium, lead, plutonium, radon, strontium, thorium, tritium ( 3 H), and uranium. This two-volume<br />

report also addresses a void that has existed on this subject in both this Agency and in the user<br />

community.<br />

It is important to note that soil scientists and geochemists knowledgeable of sorption<br />

processes in natural environments have long known that generic or default partition coefficient<br />

values found in the literature can result in significant errors when used to predict the absolute<br />

impacts of contaminant migration or site-remediation options. Accordingly, one of the major<br />

recommendations of this report is that for site-specific calculations, partition coefficient values<br />

measured at site-specific conditions are absolutely essential.<br />

For those cases when the partition coefficient parameter is not or cannot be measured,<br />

Volume II of this document: (1) provides a “thumb-nail sketch” of the key geochemical processes<br />

affecting the sorption of the selected contaminants; (2) provides references to related key<br />

experimental and review articles for further reading; (3) identifies the important aqueous- and<br />

solid-phase parameters controlling the sorption of these contaminants in the subsurface<br />

environment under oxidizing conditions; and (4) identifies, when possible, minimum and<br />

maximum conservative partition coefficient values for each contaminant as a function of the key<br />

geochemical processes affecting their sorption.<br />

iii

This publication is the result of a cooperative effort between the EPA Office of Radiation<br />

and Indoor Air, Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response, and the Department of Energy<br />

Office of Environmental Restoration (EM-40). In addition, this publication is produced as part of<br />

ORIA’s long-term strategic plan to assist in the remediation of contaminated sites. It is published<br />

and made available to assist all environmental remediation professionals in the cleanup of<br />

groundwater sources all over the United States.<br />

iv<br />

Stephen D. Page, Director<br />

Office of Radiation and Indoor Air

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS<br />

Ronald G. Wilhelm from ORIA’s Center for Remediation Technology and Tools was the<br />

project lead and EPA Project Officer for this two-volume report. Paul Beam, Environmental<br />

Restoration Program (EM-40), was the project lead and sponsor for the Department of Energy<br />

(DOE). Project support was provided by both DOE/EM-40 and EPA’s Office of Remedial and<br />

Emergency Response (OERR).<br />

EPA/ORIA wishes to thank the following people for their assistance and technical review<br />

comments on various drafts of this report:<br />

Patrick V. Brady, U.S. DOE, Sandia National Laboratories<br />

David S. Brown, U.S. EPA, National Exposure Research Laboratory<br />

Joe Eidelberg, U.S. EPA, Region 9<br />

Amy Gamerdinger, Washington State University<br />

Richard Graham, U.S. EPA, Region 8<br />

John Griggs, U.S. EPA, National Air and Radiation Environmental Laboratory<br />

David M. Kargbo, U.S. EPA, Region 3<br />

Ralph Ludwig, U.S. EPA, National Risk Management Research Laboratory<br />

Irma McKnight, U.S. EPA, Office of Radiation and Indoor Air<br />

William N. O’Steen, U.S. EPA, Region 4<br />

David J. Reisman, U.S. EPA, National Risk Management Research Laboratory<br />

Kyle Rogers, U.S. EPA, Region 5<br />

Joe R. Williams, U.S. EPA, National Risk Management Research Laboratory<br />

OSWER Regional Groundwater Forum Members<br />

In addition, special acknowledgment goes to Carey A. Johnston from ORIA’s Center for<br />

Remediation Technology and Tools for his contributions in the development, production, and<br />

review of this document.<br />

Principal authorship in production of this guide was provided by the Department of Energy’s<br />

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) under the Interagency Agreement Number<br />

DW89937220-01-03. Lynnette Downing served as the Department of Energy’s Project Officer<br />

for this Interagency Agreement. PNNL authors involved in this project include:<br />

Kenneth M. Krupka<br />

Daniel I. Kaplan<br />

Gene Whelan<br />

R. Jeffrey Serne<br />

Shas V. Mattigod<br />

v

TO COMMENT ON THIS GUIDE OR PROVIDE <strong>IN</strong>FORMATION FOR FUTURE<br />

UPDATES:<br />

Send all comments/updates to:<br />

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency<br />

Office of Radiation and Indoor Air<br />

Attention: Understanding Variation in Partition (K d) Values<br />

401 M Street, SW (6602J)<br />

Washington, DC 20460<br />

or<br />

webmaster.oria@epa.gov<br />

vi

ABSTRACT<br />

This two-volume report describes the conceptualization, measurement, and use of the partition (or<br />

distribution) coefficient, K d, parameter, and the geochemical aqueous solution and sorbent<br />

properties that are most important in controlling adsorption/retardation behavior of selected<br />

contaminants. The report is provided for technical staff from EPA and other organizations who<br />

are responsible for prioritizing site remediation and waste management decisions. Volume I<br />

discusses the technical issues associated with the measurement of K d values and its use in<br />

formulating the retardation factor, R f. The K d concept and methods for measurement of K d values<br />

are discussed in detail in Volume I. Particular attention is directed at providing an understanding<br />

of: (1) the use of K d values in formulating R f, (2) the difference between the original<br />

thermodynamic K d parameter derived from ion-exchange literature and its “empiricized” use in<br />

contaminant transport codes, and (3) the explicit and implicit assumptions underlying the use of<br />

the K d parameter in contaminant transport codes. A conceptual overview of chemical reaction<br />

models and their use in addressing technical defensibility issues associated with data from K d<br />

studies is presented. The capabilities of EPA’s geochemical reaction model M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 and its<br />

different conceptual adsorption models are also reviewed. Volume II provides a “thumb-nail<br />

sketch” of the key geochemical processes affecting the sorption of selected inorganic<br />

contaminants, and a summary of K d values given in the literature for these contaminants under<br />

oxidizing conditions. The contaminants chosen for the first phase of this project include<br />

chromium, cadmium, cesium, lead, plutonium, radon, strontium, thorium, tritium ( 3 H), and<br />

uranium. Important aqueous speciation, (co)precipitation/dissolution, and adsorption reactions<br />

are discussed for each contaminant. References to related key experimental and review articles<br />

for further reading are also listed.<br />

vii

CONTENTS<br />

NOTICE ..................................................................ii<br />

FOREWORD ............................................................. iii<br />

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .....................................................v<br />

FUTURE UPDATES ....................................................... vi<br />

ABSTRACT ..............................................................vii<br />

LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................ xiii<br />

LIST OF TABLES .........................................................xv<br />

1.0 Introduction .......................................................... 1.1<br />

2.0 The K d Model ......................................................... 2.1<br />

3.0 Methods, Issues, and Criteria for Measuring K d Values .......................... 3.1<br />

viii<br />

Page<br />

3.1 Laboratory Batch Methods ............................................ 3.1<br />

3.2 Laboratory Flow-Through Method ...................................... 3.1<br />

3.3 Other Methods ..................................................... 3.2<br />

3.4 Issues ............................................................ 3.2<br />

4.0 Application of Chemical Reaction Models .................................... 4.1<br />

5.0 Contaminant Geochemistry and K d Values ................................... 5.1<br />

5.1 General ........................................................... 5.1<br />

5.2 Cadmium Geochemistry and K d Values ................................... 5.5<br />

5.2.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation .......................................... 5.5<br />

5.2.2 General Geochemistry ........................................... 5.5<br />

5.2.3 Aqueous Speciation ............................................. 5.6<br />

5.2.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ............................. 5.8<br />

5.2.5 Sorption/Desorption ............................................. 5.9<br />

5.2.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values .................................. 5.10<br />

5.2.6.1 General Availability of K d Values .............................. 5.10<br />

5.2.6.2 Look-Up Tables .......................................... 5.11<br />

5.2.6.2.1 Limits of K d Values with Aluminum/Iron-Oxide Concentrations ..... 5.11<br />

5.2.6.2.2 Limits of K d Values with Respect to CEC ...................... 5.12<br />

5.2.6.2.3 Limits of K d Values with Respect to Clay Concentrations .......... 5.12<br />

5.2.6.2.4 Limits of K d Values with Respect to Concentration of<br />

Organic Matter .......................................... 5.12

5.2.6.2.5 Limits of K d Values with Respect to Dissolved Calcium,<br />

Magnesium, and Sulfide Concentrations, and Redox Conditions ..... 5.12<br />

5.3 Cesium Geochemistry and K d Values .................................... 5.13<br />

5.3.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ......................................... 5.13<br />

5.3.2 General Geochemistry .......................................... 5.13<br />

5.3.3 Aqueous Speciation ............................................ 5.13<br />

5.3.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ............................ 5.14<br />

5.3.5 Sorption/Desorption ............................................ 5.14<br />

5.3.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values .................................. 5.15<br />

5.3.6.1 General Availability of K d Data ............................... 5.15<br />

5.3.6.2 Look-Up Tables .......................................... 5.16<br />

5.3.6.2.1 Limits of K d with Respect to pH ......................... 5.18<br />

5.3.6.2.2 Limits of K d with Respect to Potassium, Ammonium,<br />

and Aluminum/Iron-Oxide Concentrations ................. 5.18<br />

5.4 Chromium Geochemistry and K d Values ................................. 5.18<br />

5.4.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ........................................... 5.18<br />

5.4.2 General Geochemistry .......................................... 5.18<br />

5.4.3 Aqueous Speciation ............................................ 5.19<br />

5.4.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ............................ 5.19<br />

5.4.5 Sorption/Desorption ............................................ 5.20<br />

5.4.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values .................................. 5.21<br />

5.4.6.1 General Availability of K d Data ................................ 5.21<br />

5.4.6.2 Look-Up Tables ........................................... 5.22<br />

5.4.6.2.1 Limits of K d with Respect to pH ......................... 5.23<br />

5.4.6.2.2 Limits of K d with Respect to Extractable Iron Content ......... 5.23<br />

5.4.6.2.3 Limits of K d with Respect to Competing Anion Concentrations .. 5.23<br />

5.5 Lead Geochemistry and K d Values ..................................... 5.25<br />

5.5.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ........................................... 5.25<br />

5.5.2 General Geochemistry .......................................... 5.25<br />

5.5.3 Aqueous Speciation ............................................ 5.26<br />

5.5.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ............................ 5.27<br />

5.5.5 Sorption/Desorption ............................................ 5.30<br />

5.5.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values .................................. 5.31<br />

5.5.6.1 General Availability of K d Data ................................ 5.31<br />

5.5.6.2 K d Look-Up Tables ........................................ 5.33<br />

5.5.6.2.1 Limits of K d with Respect to pH ......................... 5.33<br />

5.5.6.2.2 Limits of K d with Respect to Equilibrium Lead<br />

ix

Concentrations Extractable Iron Content ........................ 5.34<br />

5.6 Plutonium Geochemistry and K d Values ................................. 5.34<br />

5.6.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ......................................... 5.34<br />

5.6.2 General Geochemistry .......................................... 5.34<br />

5.6.3 Aqueous Speciation ............................................ 5.35<br />

5.6.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ............................ 5.37<br />

5.6.5 Sorption/Desorption ............................................ 5.40<br />

5.6.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values .................................. 5.41<br />

5.6.6.1 General Availability of K d Data ............................... 5.41<br />

5.6.6.2 K d Look-Up Tables ....................................... 5.43<br />

5.6.6.2.1 Limits of K d with Respect to Clay Content .................. 5.43<br />

5.6.6.2.2 Limits of K d with Respect to Dissolved Carbonate<br />

Concentrations ....................................... 5.44<br />

5.7 Radon Geochemistry and K d Values .................................... 5.44<br />

5.7.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ......................................... 5.44<br />

5.7.2 General Geochemistry .......................................... 5.45<br />

5.7.3 Aqueous Speciation ............................................ 5.45<br />

5.7.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ............................ 5.46<br />

5.7.5 Sorption/Desorption ............................................ 5.46<br />

5.7.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values .................................. 5.46<br />

5.8 Strontium Geochemistry and K d Values .................................. 5.46<br />

5.8.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ......................................... 5.46<br />

5.8.2 General Geochemistry .......................................... 5.47<br />

5.8.3 Aqueous Speciation ............................................ 5.47<br />

5.8.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ............................ 5.48<br />

5.8.5 Sorption/Desorption ............................................ 5.49<br />

5.8.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values .................................. 5.51<br />

5.8.6.1 General Availability of K d Data ............................... 5.51<br />

5.8.6.2 Look-Up Tables .......................................... 5.51<br />

5.8.6.2.1 Limits of K d with Respect to pH, CEC, and<br />

Clay Concentrations Values ............................ 5.52<br />

5.8.6.2.2 Limits of K d with Respect to Dissolved Calcium<br />

Concentrations ...................................... 5.52<br />

5.8.6.2.3 Limits of K d with Respect to Dissolved Stable<br />

Strontium and Carbonate Concentrations .................. 5.53<br />

5.9 Thorium Geochemistry and K d Values ................................... 5.53<br />

x

5.9.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ......................................... 5.53<br />

5.9.2 General Geochemistry .......................................... 5.54<br />

5.9.3 Aqueous Speciation ............................................ 5.55<br />

5.9.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ............................ 5.58<br />

5.9.5 Sorption/Desorption ............................................ 5.60<br />

5.9.6 Partition Coefficient, K d, Values ................................... 5.61<br />

5.9.6.1 General Availability of K d Data ............................... 5.61<br />

5.9.6.2 Look-Up Tables .......................................... 5.62<br />

5.9.6.2.1 Limits of K d with Respect to Organic Matter and<br />

Aluminum/Iron-Oxide Concentrations .................... 5.63<br />

5.9.6.2.2 Limits of K d with Respect to Dissolved Carbonate<br />

Concentrations ....................................... 5.63<br />

5.10 Tritium Geochemistry and K d Values ................................... 5.64<br />

5.10.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ........................................ 5.64<br />

5.10.2 General Geochemistry ......................................... 5.64<br />

5.10.3 Aqueous Speciation ........................................... 5.65<br />

5.10.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ........................... 5.65<br />

5.10.5 Sorption/Desorption ........................................... 5.65<br />

5.10.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values ................................. 5.65<br />

5.11 Uranium Geochemistry and K d Values .................................. 5.65<br />

5.11.1 Overview: Important Aqueous- and Solid-Phase Parameters<br />

Controlling Retardation ........................................ 5.65<br />

5.11.2 General Geochemistry ......................................... 5.66<br />

5.11.3 Aqueous Speciation ........................................... 5.67<br />

5.11.4 Dissolution/Precipitation/Coprecipitation ........................... 5.69<br />

5.11.5 Sorption/Desorption ........................................... 5.72<br />

5.11.6 Partition Coefficient, K d , Values ................................. 5.74<br />

5.11.6.1 General Availability of K d Data .............................. 5.74<br />

5.11.6.2 Look-Up Table .......................................... 5.74<br />

5.11.6.2.1 Limits K d Values with Respect to Dissolved<br />

Carbonate Concentrations ............................. 5.75<br />

5.11.6.2.2 Limits of K d Values with Respect to Clay Content and CEC ... 5.76<br />

5.11.6.2.3 Use of Surface Complexation Models to Predict<br />

Uranium K d Values .................................. 5.76<br />

5.12 Conclusions ..................................................... 5.77<br />

6.0 References ........................................................... 6.1<br />

xi

Appendix A - Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................A.1<br />

Appendix B - Definitions .................................................... B.1<br />

Appendix C - Partition Coefficients for Cadmium ................................. C.1<br />

Appendix D - Partition Coefficients for Cesium ...................................D.1<br />

Appendix E - Partition Coefficients for Chromium ................................. E.1<br />

Appendix F - Partition Coefficients for Lead ..................................... F.1<br />

Appendix G - Partition Coefficients for Plutonium ................................G.1<br />

Appendix H - Partition Coefficients for Strontium .................................H.1<br />

Appendix I - Partition Coefficients for Thorium ................................... I.1<br />

Appendix J - Partition Coefficients for Uranium ................................... J.1<br />

xii

LIST OF FIGURES<br />

Figure 5.1. Calculated distribution of cadmium aqueous species as a function of pH<br />

for the water composition in Table 5.1 ............................. 5.7<br />

Figure 5.2. Calculated distribution of lead aqueous species as a function of<br />

pH for the water composition listed in Table 5.1 ..................... 5.29<br />

Figure 5.3. Calculated distribution of plutonium aqueous species as a function of<br />

pH for the water composition in Table 5.1. ......................... 5.39<br />

Figure 5.4. Calculated distribution of thorium hydrolytic species as a function of pH. .. 5.57<br />

Figure 5.5. Calculated distribution of thorium aqueous species as a function of<br />

pH for the water composition in Table 5.1. ......................... 5.59<br />

Figure 5.6a. Calculated distribution of U(VI) hydrolytic species as a function of<br />

pH at 0.1 µg/l total dissolved U(VI) .............................. 5.70<br />

Figure 5.6b. Calculated distribution of U(VI) hydrolytic species as a function of pH<br />

at 1,000 µg/l total dissolved U(VI) ............................... 5.71<br />

Figure 5.7. Calculated distribution of U(VI) aqueous species as a function of pH<br />

for the water composition in Table 5.1 ............................ 5.72<br />

Figure C.1. Relation between cadmium K d values and pH in soils ................... C.5<br />

Figure D.1. Relation between cesium K d values and CEC .........................D.7<br />

Figure D.2. Relation between CEC and clay content ............................D.8<br />

Figure D.3. K d values calculated from an overall literature Fruendlich equation for<br />

cesium (Equation D.2) ........................................D.12<br />

Figure D.4. Generalized cesium Freundlich equation (Equation D.3) derived<br />

from the literature ............................................D.16<br />

Figure D.5. Cesium K d values calculated from generalized Fruendlich equation<br />

(Equations D.3 and D.4) derived from the literature ..................D.16<br />

xiii<br />

Page

Figure E.1. Variation of K d for Cr(VI) as a function of pH and DCB extractable<br />

Iron content without the presence of competing anions ................ E.10<br />

Figure F.1. Correlative relationship between K d and pH .......................... F.6<br />

Figure F.2. Variation of K d as a function of pH and the equilibrium<br />

lead concentrations. ............................................ F.7<br />

Figure G.1. Scatter plot matrix of soil properties and the partition<br />

coefficient (K d) of plutonium ....................................G.12<br />

Figure G.2. Variation of K d for plutonium as a function of clay content and<br />

dissolved carbonate concentrations. ...............................G.14<br />

Figure H.1. Relation between strontium K d values and CEC in soils. ................H.5<br />

Figure H.2. Relation between strontium K d values for soils with CEC<br />

values less than 15 meq/100 g. ...................................H.7<br />

Figure H.3. Relation between strontium K d values and soil clay content ..............H.7<br />

Figure H.4. Relation between strontium K d values and soil pH .....................H.9<br />

Figure I.1. Linear regression between thorium K d values and pH for the pH<br />

range from 4 to 8 ............................................. I.5<br />

Figure I.2. Linear regression between thorium K d values and pH for the pH<br />

range from 4 to 8 ............................................. I.8<br />

Figure J.1. Field-derived K d values for 238 U and 235 U from Serkiz and Johnson (1994)<br />

plotted as a function of porewater pH for contaminated<br />

soil/porewater samples ......................................... J.8<br />

Figure J.2. Field-derived K d values for 238 U and 235 U from Serkiz and Johnson (1994)<br />

plotted as a function of the weight percent of clay-size particles in the<br />

contaminated soil/porewater samples ............................... J.9<br />

Figure J.3. Field-derived K d values for 238 U and 235 U plotted from Serkiz and Johnson (1994)<br />

as a function of CEC (meq/kg) of the contaminated<br />

soil/porewater samples ........................................ J.10<br />

Figure J.4. Uranium K d values used for development of K d look-up table ........... J.19<br />

xiv

LIST OF TABLES<br />

Table 5.1. Estimated mean composition of river water of the world from Hem (1985) ...... 5.3<br />

Table 5.2. Concentrations of contaminants used in the aqueous species<br />

distribution calculations. ............................................ 5.4<br />

Table 5.3. Cadmium aqueous species included in the speciation calculations ............. 5.6<br />

Table 5.4. Estimated range of K d values for cadmium as a function of pH. ............. 5.11<br />

Table 5.5. Estimated range of K d values (ml/g) for cesium based on CEC<br />

or clay content for systems containing

Table 5.16. Uranium(VI) aqueous species included in the speciation calculations. ........ 5.69<br />

Table 5.17. Look-up table for estimated range of K d values for uranium based on pH ..... 5.75<br />

Table 5.18. Selected chemical and transport properties of the contaminants. ............ 5.78<br />

Table 5.19. Distribution of dominant contaminant species at 3 pH<br />

values for an oxidizing water described in Tables 5.1 and 5.2. .............. 5.79<br />

Table 5.20. Some of the more important aqueous- and solid-phase parameters<br />

affecting contaminant sorption ..................................... 5.81<br />

Table C.1. Descriptive statistics of the cadmium K d data set for soils ................... C.3<br />

Table C.2. Correlation coefficients (r) of the cadmium K d data set for soils .............. C.4<br />

Table C.3. Look-up table for estimated range of K d values for cadmium based on pH ...... C.5<br />

Table C.4. Cadmium K d data set for soils. ....................................... C.6<br />

Table D.1. Descriptive statistics of cesium K d data set including<br />

soil and pure mineral phases. ........................................D.3<br />

Table D.2. Descriptive statistics of data set including soils only. ......................D.4<br />

Table D.3. Correlation coefficients (r) of the cesium K d value data set that<br />

included soils and pure mineral phases. ................................D.6<br />

Table D.4. Correlation coefficients (r) of the soil-only data set. .......................D.6<br />

Table D.5. Effect of mineralogy on cesium exchange. ..............................D.9<br />

Table D.6 Cesium K d values measured on mica (Fithian illite) via adsorption<br />

and desorption experiments. ........................................D.10<br />

Table D.7. Approximate upper limits of linear range of adsorption isotherms on<br />

various solid phases. .............................................D.11<br />

Table D.8. Fruendlich equations identified in literature for cesium. ...................D.13<br />

Table D.9. Descriptive statistics of the cesium Freundlich equations (Table D.8)<br />

reported in the literature. ..........................................D.15<br />

xvi

Table D.10. Estimated range of K d values (ml/g) for cesium based on CEC<br />

or clay content for systems containing

Table H.3. Simple and multiple regression analysis results involving<br />

strontium K d values, CEC (meq/100 g), pH, and clay content (percent). ........H.8<br />

Table H.4. Look-up table for estimated range of K d values for strontium based<br />

on CEC and pH. .................................................H.10<br />

Table H.5. Look-up table for estimated range of K d values for strontium based on<br />

clay content and pH. ..............................................H.10<br />

Table H.6. Calculations of clay content using regression equations containing<br />

CEC as a independent variable. ......................................H.11<br />

Table H.7. Strontium K d data set for soils. .....................................H.12<br />

Table H.8. Strontium K d data set for pure mineral phases and soils ...................H.16<br />

Table I.1. Descriptive statistics of thorium K d value data set presented in Section I.3. ...... I.3<br />

Table I.2. Correlation coefficients (r) of the thorium K d value data set presented<br />

in Section I.3. .................................................... I.4<br />

Table I.3. Calculated aqueous speciation of thorium as a function of pH. ............... I.5<br />

Table I.4. Regression coefficient and their statistics relating thorium K d values and pH. ..... I.6<br />

Table I.5. Look-up table for thorium K d values (ml/g) based on pH and<br />

dissolved thorium concentrations. ..................................... I.7<br />

Table I.6. Data set containing thorium K d values. ................................. I.9<br />

Table J.1. Uranium K d values (ml/g) listed by Warnecke et al. (1994, Table 1). ......... J.12<br />

Table J.2. Uranium K d values listed by McKinley and Scholtis (1993, Tables 1, 2,<br />

and 4) from sorption databases used by different international organizations for<br />

performance assessments of repositories for radioactive wastes. ............ J.17<br />

xviii

Table J.3. Geometric mean uranium K d values derived by Thibault et al.<br />

(1990) for sand, loam, clay, and organic soil types. ....................... J.18<br />

Table J.4. Look-up table for estimated range of K d values for uranium based on pH. ...... J.22<br />

Table J.5. Uranium K d values selected from literature for development<br />

of look-up table. ................................................. J.29<br />

xix

1.0 Introduction<br />

The objective of the report is to provide a reasoned and documented discussion on the technical<br />

issues associated with the measurement and selection of partition (or distribution) coefficient,<br />

K d, 1,2 values and their use in formulating the retardation factor, R f. The contaminant retardation<br />

factor (R f) is the parameter commonly used in transport models to describe the chemical<br />

interaction between the contaminant and geological materials (i.e., soil, sediments, rocks, and<br />

geological formations, henceforth simply referred to as soils 3 ). It includes processes such as<br />

surface adsorption, absorption into the soil structure, precipitation, and physical filtration of<br />

colloids. Specifically, it describes the rate of contaminant transport relative to that of<br />

groundwater. This report is provided for technical staff from EPA and other organizations who<br />

are responsible for prioritizing site remediation and waste management decisions. The<br />

two-volume report describes the conceptualization, measurement, and use of the K d parameter;<br />

and geochemical aqueous solution and sorbent properties that are most important in controlling<br />

the adsorption/retardation behavior of a selected set of contaminants.<br />

This review is not meant to assess or judge the adequacy of the K d approach used in modeling<br />

tools for estimating adsorption and transport of contaminants and radionuclides. Other<br />

approaches, such as surface complexation models, certainly provide more robust mechanistic<br />

approaches for predicting contaminant adsorption. However, as one reviewer of this volume<br />

noted, “K d’s are the coin of the realm in this business.” For better or worse, the K d model is<br />

integral part of current methodologies for modeling contaminant and radionuclide transport and<br />

risk analysis.<br />

The K d concept, its use in fate and transport computer codes, and the methods for the<br />

measurement of K d values are discussed in detail in Volume I and briefly introduced in Chapters 2<br />

and 3 in Volume II. Particular attention is directed at providing an understanding of: (1) the use<br />

of K d values in formulating R f, (2) the difference between the original thermodynamic K d<br />

parameter derived from the ion-exchange literature and its “empiricized” use in contaminant<br />

1 Throughout this report, the term “partition coefficient” will be used to refer to the <strong>Kd</strong> “linear<br />

isotherm” sorption model. It should be noted, however, that the terms “partition coefficient” and<br />

“distribution coefficient” are used interchangeably in the literature for the K d model.<br />

2 A list of acronyms, abbreviations, symbols, and notation is given in Appendix A. A list of<br />

definitions is given in Appendix B<br />

3 The terms “sediment” and “soil” have particular meanings depending on one’s technical<br />

discipline. For example, the term “sediment” is often reserved for transported and deposited<br />

particles derived from soil, rocks, or biological material. “Soil” is sometimes limited to referring<br />

to the top layer of the earth’s surface, suitable for plant life. In this report, the term “soil” was<br />

selected with concurrence of the EPA Project Officer as a general term to refer to all<br />

unconsolidated geologic materials.<br />

1.1

transport codes, and (3) the explicit and implicit assumptions underlying the use of the K d<br />

parameter in contaminant transport codes.<br />

The K d parameter is very important in estimating the potential for the adsorption of dissolved<br />

contaminants in contact with soil. As typically used in fate and contaminant transport<br />

calculations, the K d is defined as the ratio of the contaminant concentration associated with the<br />

solid to the contaminant concentration in the surrounding aqueous solution when the system is at<br />

equilibrium. Soil chemists and geochemists knowledgeable of sorption processes in natural<br />

environments have long known that generic or default K d values can result in significant errors<br />

when used to predict the impacts of contaminant migration or site-remediation options. To<br />

address some of this concern, modelers often incorporate a degree of conservatism into their<br />

calculations by selecting limiting or bounding conservative K d values. For example, the most<br />

conservative (i.e., maximum) estimate from the perspective of off-site risks due to contaminant<br />

migration through the subsurface natural soil and groundwater systems is to assume that the soil<br />

has little or no ability to slow (retard) contaminant movement (i.e., a minimum bounding K d<br />

value). Consequently, the contaminant would travel in the direction and at the rate of water.<br />

Such an assumption may in fact be appropriate for certain contaminants such as tritium, but may<br />

be too conservative for other contaminants, such as thorium or plutonium, which react strongly<br />

with soils and may migrate 10 2 to 10 6 times more slowly than the water. On the other hand, when<br />

estimating the risks and costs associated with on-site remediation options, a maximum bounding<br />

K d value provides an estimate of the maximum concentration of a contaminant or radionuclide<br />

sorbed to the soil. Due to groundwater flow paths, site characteristics, or environmental<br />

uncertainties, the final results of risk and transport calculations for some contaminants may be<br />

insensitive to the K d value even when selected within the range of technically-defensible, limiting<br />

minimum and maximum K d values. For those situations that are sensitive to the selected K d value,<br />

site-specific K d values are essential.<br />

The K d is usually a measured parameter that is obtained from laboratory experiments. The<br />

5 general methods used to measure K d values are reviewed. These methods include the batch<br />

laboratory method, the column laboratory method, field-batch method, field modeling method,<br />

and K oc method. The summary identifies what the ancillary information is needed regarding the<br />

adsorbent (soil), solution (contaminated ground-water or process waste water), contaminant<br />

(concentration, valence state, speciation distribution), and laboratory details (spike addition<br />

methodology, phase separation techniques, contact times). The advantages, disadvantages, and,<br />

perhaps more importantly, the underlying assumptions of each method are also presented.<br />

A conceptual overview of geochemical modeling calculations and computer codes as they pertain<br />

to evaluating K d values and modeling of adsorption processes is discussed in detail in Volume I<br />

and briefly described in Chapter 4 of Volume II. The use of geochemical codes in evaluating<br />

aqueous speciation, solubility, and adsorption processes associated with contaminant fate studies<br />

is reviewed. This approach is compared to the traditional calculations that rely on the constant K d<br />

construct. The use of geochemical modeling to address quality assurance and technical<br />

defensibility issues concerning available K d data and the measurement of K d values is also<br />

1.2

discussed. The geochemical modeling review includes a brief description of the EPA’s<br />

M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 geochemical code and a summary of the types of conceptual models it contains to<br />

quantify adsorption reactions. The status of radionuclide thermodynamic and contaminant<br />

adsorption model databases for the M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 code is also reviewed.<br />

The main focus of Volume II is to: (1) provide a “thumb-nail sketch” of the key geochemical<br />

processes affecting the sorption of a selected set of contaminants; (2) provide references to<br />

related key experimental and review articles for further reading; (3) identify the important<br />

aqueous- and solid-phase parameters controlling the sorption of these contaminants in the<br />

subsurface environment; and (4) identify, when possible, minimum and maximum conservative K d<br />

values for each contaminant as a function key geochemical processes affecting their sorption. The<br />

contaminants chosen for the first phase of this project include cadmium, cesium, chromium, lead,<br />

plutonium, radon, strontium, thorium, tritium ( 3 H), and uranium. The selection of these<br />

contaminants by EPA and PNNL project staff was based on 2 criteria. First, the contaminant had<br />

to be of high priority to the site remediation or risk assessment activities of EPA, DOE, and/or<br />

NRC. Second, because the available funding precluded a review of all contaminants that met the<br />

first criteria, a subset was selected to represent categories of contaminants based on their chemical<br />

behavior. The six nonexclusive categories are:<br />

C Cations - cadmium, cesium, plutonium, strontium, thorium, and uranium(VI).<br />

C Anions - chromium(VI) (as chromate) and uranium(VI).<br />

C Radionuclides - cesium, plutonium, radon, strontium, thorium, tritium ( 3 H), and uranium.<br />

C Conservatively transported contaminants - tritium ( 3 H) and radon.<br />

C Nonconservatively transported contaminants - other than tritium ( 3 H) and radon.<br />

C Redox sensitive elements - chromium, plutonium, and uranium.<br />

The general geochemical behaviors discussed in this report can be used by analogy to estimate the<br />

geochemical interactions of similar elements for which data are not available. For example,<br />

contaminants present primarily in anionic form, such as Cr(VI), tend to adsorb to a limited extent<br />

to soils. Thus, one might generalize that other anions, such as nitrate, chloride, and<br />

U(VI)-anionic complexes, would also adsorb to a limited extent. Literature on the adsorption of<br />

these 3 solutes show no or very little adsorption.<br />

The concentration of contaminants in groundwater is controlled primarily by the amount of<br />

contaminant present at the source; rate of release from the source; hydrologic factors such as<br />

dispersion, advection, and dilution; and a number of geochemical processes including aqueous<br />

geochemical processes, adsorption/desorption, precipitation, and diffusion. To accurately predict<br />

contaminant transport through the subsurface, it is essential that the important geochemical<br />

processes affecting contaminant transport be identified and, perhaps more importantly, accurately<br />

described in a mathematically and scientifically defensible manner. Dissolution/precipitation and<br />

adsorption/desorption are usually the most important processes affecting contaminant interaction<br />

with soils. Dissolution/precipitation is more likely to be the key process where chemical<br />

nonequilibium exists, such as at a point source, an area where high contaminant concentrations<br />

1.3

exist, or where steep pH or oxidation-reduction (redox) gradients exist. Adsorption/desorption<br />

will likely be the key process controlling contaminant migration in areas where chemical steady<br />

state exist, such as in areas far from the point source. Diffusion flux spreads solute via a<br />

concentration gradient (i.e., Fick’s law). Diffusion is a dominant transport mechanism when<br />

advection is insignificant, and is usually a negligible transport mechanism when water is being<br />

advected in response to various forces.<br />

1.4

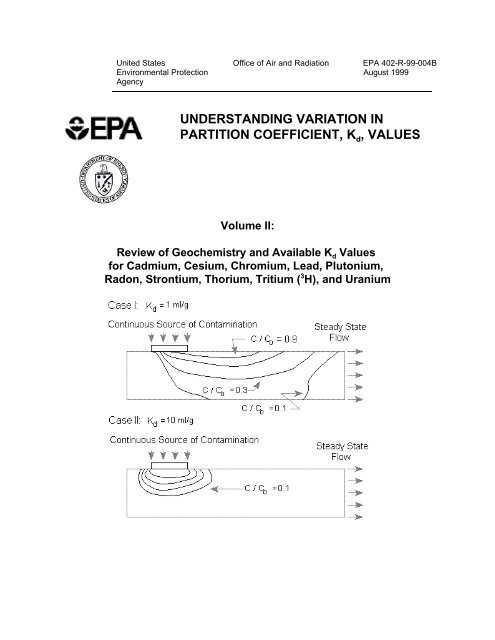

2.0 The K d Model<br />

The simplest and most common method of estimating contaminant retardation is based on the<br />

partition (or distribution) coefficient, K d. The K d parameter is a factor related to the partitioning<br />

of a contaminant between the solid and aqueous phases. It is an empirical unit of measurement<br />

that attempts to account for various chemical and physical retardation mechanisms that are<br />

influenced by a myriad of variables. The K d metric is the most common measure used in transport<br />

codes to describe the extent to which contaminants are sorbed to soils. It is the simplest, yet least<br />

robust model available. A primary advantage of the K d model is that it is easily inserted into<br />

hydrologic transport codes to quantify reduction in the rate of transport of the contaminant<br />

relative to groundwater, either by advection or diffusion. Technical issues, complexities, and<br />

shortcomings of the K d approach to describing contaminant sorption to soils are summarized in<br />

detail in Chapter 2 of Volume I. Particular attention is directed at issues relevant to the selection<br />

of K d values from the literature for use in transport codes.<br />

The partition coefficient, K d, is defined as the ratio of the quantity of the adsorbate adsorbed per<br />

mass of solid to the amount of the adsorbate remaining in solution at equilibrium. For the<br />

reaction<br />

the mass action expression for K d is<br />

K d '<br />

A % C i ' A i , (2.1)<br />

Mass of Adsorbate Sorbed<br />

Mass of Adsorbate in Solution ' A i<br />

C i<br />

where A = free or unoccupied surface adsorption sites<br />

C i = total dissolved adsorbate remaining in solution at equilibrium<br />

A i = amount of adsorbate on the solid at equilibrium.<br />

The K d is typically given in units of ml/g. Describing the K d in terms of this simple reaction<br />

assumes that A is in great excess with respect to C i and that the activity of A i is equal to 1.<br />

Chemical retardation, R f, is defined as,<br />

R f ' v p<br />

v c<br />

where v p = velocity of the water through a control volume<br />

v c = velocity of contaminant through a control volume.<br />

2.1<br />

(2.2)<br />

, (2.3)<br />

The chemical retardation term does not equal unity when the solute interacts with the soil; almost<br />

always the retardation term is greater than 1 due to solute sorption to soils. In rare cases, the

etardation factor is actually less than 1, and such circumstances are thought to be caused by<br />

anion exclusion (See Volume I, Section 2.8). Knowledge of the K d and of media bulk density and<br />

porosity for porous flow, or of media fracture surface area, fracture opening width, and matrix<br />

diffusion attributes for fracture flow, allows calculation of the retardation factor. For porous flow<br />

with saturated moisture conditions, the R f is defined as<br />

R f ' 1 % D b<br />

n e<br />

where D b = porous media bulk density (mass/length 3 )<br />

n e = effective porosity of the media at saturation.<br />

The K d parameter is valid only for a particular adsorbent and applies only to those aqueous<br />

chemical conditions (e.g., adsorbate concentration, solution/electrolyte matrix) in which it was<br />

measured. Site-specific K d values should be used for site-specific contaminant and risk<br />

assessment calculations. Ideally, site-specific K d values should be measured for the range of<br />

aqueous and geological conditions in the system to be modeled. However, literature-derived K d<br />

values are commonly used for screening calculations. Suitable selection and use of literaturederived<br />

K d values for use in screening calculations of contaminant transport is not a trivial matter.<br />

Among the assumptions implicit with the K d construct is: (1) only trace amounts of contaminants<br />

exist in the aqueous and solid phases, (2) the relationship between the amount of contaminant in<br />

the solid and liquid phases is linear, (3) equilibrium conditions exist, (4) equally rapid adsorption<br />

and desorption kinetics exists, (5) it describes contaminant partitioning between 1 sorbate<br />

(contaminant) and 1 sorbent (soil), and (6) all adsorption sites are accessible and have equal<br />

strength. The last point is especially limiting for groundwater contaminant models because it<br />

requires that K d values should be used only to predict transport in systems chemically identical to<br />

those used in the laboratory measurement of the K d. Variation in either the soil or aqueous<br />

chemistry of a system can result in extremely large differences in K d values.<br />

A more robust approach than using a single K d to describe the partitioning of contaminants<br />

between the aqueous and solid phases is the parametric-K d model. This model varies the K d value<br />

according to the chemistry and mineralogy of the system at the node being modeled. The<br />

parametric-K d value, unlike the constant-K d value, is not limited to a single set of environmental<br />

conditions. Instead, it describes the sorption of a contaminant in the range of environmental<br />

conditions used to create the parametric-K d equations. These types of statistical relationships are<br />

devoid of causality and therefore provide no information on the mechanism by which the<br />

radionuclide partitioned to the solid phase, whether it be by adsorption, absorption, or<br />

precipitation. Understanding these mechanisms is extremely important relative to estimating the<br />

mobility of a contaminant.<br />

When the parametric-K d model is used in the transport equation, the code must also keep track of<br />

the current value of the independent variables at each point in space and time to continually<br />

update the concentration of the independent variables affecting the K d value. Thus, the code must<br />

2.2<br />

K d<br />

(2.4)

track many more parameters and some numerical solving techniques (such as closed-form<br />

analytical solutions) can no longer be used to perform the integration necessary to solve for the K d<br />

value and/or retardation factor, R f. Generally, computer codes that can accommodate the<br />

parametric-K d model use a chemical subroutine to update the K d value used to determine the R F,<br />

when called by the main transport code. The added complexity in solving the transport equation<br />

with the parametric-K d sorption model and its empirical nature may be the reasons this approach<br />

has been used sparingly.<br />

Mechanistic models explicitly accommodate for the dependency of K d values on contaminant concentration,<br />

charge, competing ion concentration, variable surface charge on the soil, and solution<br />

species distribution. Incorporating mechanistic adsorption concepts into transport models is<br />

desirable because the models become more robust and, perhaps more importantly from the<br />

standpoint of regulators and the public, scientifically defensible. However, truly mechanistic<br />

adsorption models are rarely, if ever, applied to complex natural soils. The primary reason for this<br />

is because natural mineral surfaces are very irregular and difficult to characterize. These surfaces<br />

consist of many different microcrystalline structures that exhibit quite different chemical<br />

properties when exposed to solutions. Thus, examination of the surface by virtually any<br />

experimental method yields only averaged characteristics of the surface and the interface.<br />

Less attention will be directed to mechanistic models because they are not extensively<br />

incorporated into the majority of EPA, DOE, and NRC modeling methodologies. The complexity<br />

of installing these mechanistic adsorption models into existing transport codes is formidable.<br />

Additionally, these models also require a more extensive database collection effort than will likely<br />

be available to the majority of EPA, DOE, and NRC contaminant transport modelers. A brief<br />

description of the state of the science is presented in Volume I primarily to provide a paradigm for<br />

sorption processes.<br />

2.3

3.0 Methods, Issues, and Criteria for Measuring K d Values<br />

There are 5 general methods used to measure K d values: the batch laboratory method, laboratory<br />

flow-through (or column) method, field-batch method, field modeling method, and K oc method.<br />

These methods and the associated technical issues are described in detail in Chapter 3 of Volume<br />

I. Each method has advantages and disadvantages, and perhaps more importantly, each method<br />

has its own set of assumptions for calculating K d values from experimental data. Consequently, it<br />

is not only common, but expected that K d values measured by different methods will produce<br />

different values.<br />

3.1 Laboratory Batch Method<br />

Batch tests are commonly used to measure K d values. The test is conducted by spiking a solution<br />

with the element of interest, mixing the spiked solution with a solid for a specified period of time,<br />

separating the solution from the solid, and measuring the concentration of the spiked element<br />

remaining in solution. The concentration of contaminant associated with the solid is determined<br />

by the difference between initial and final contaminant concentration. The primary advantage of<br />

the method is that such experiments can be completed quickly for a wide variety of elements and<br />

chemical environments. The primary disadvantage of the batch technique for measuring K d is that<br />

it does not necessarily reproduce the chemical reaction conditions that take place in the real<br />

environment. For instance, in a soil column, water passes through at a finite rate and both<br />

reaction time and degree of mixing between water and soil can be much less than those occurring<br />

in a laboratory batch test. Consequently, K d values from batch experiments can be high relative to<br />

the extent of sorption occurring in a real system, and thus result in an estimate of contaminant<br />

retardation that is too large. Another disadvantage of batch experiments is that they do not<br />

accurately simulate desorption of the radionuclides or contaminants from a contaminated soil or<br />

solid waste source. The K d values are frequently used with the assumption that adsorption and<br />

desorption reactions are reversible. This assumption is contrary to most experimental<br />

observations that show that the desorption process is appreciably slower than the adsorption<br />

process, a phenomenon referred to as hysteresis. The rate of desorption may even go to zero, yet<br />

a significant mass of the contaminant remains sorbed on the soil. Thus, use of K d values<br />

determined from batch adsorption tests in contaminant transport models is generally considered to<br />

provide estimates of contaminant remobilization (release) from soil that are too large (i.e.,<br />

estimates of contaminant retention that are too low).<br />

3.2 Laboratory Flow-Through Method<br />

Flow-through column experiments are intended to provide a more realistic simulation of dynamic<br />

field conditions and to quantify the movement of contaminants relative to groundwater flow. It is<br />

the second most common method of determining K d values. The basic experiment is completed<br />

by passing a liquid spiked with the contaminant of interest through a soil column. The column<br />

experiment combines the chemical effects of sorption and the hydrologic effects of groundwater<br />

flow through a porous medium to provide an estimate of retarded movement of the contaminant<br />

3.1

of interest. The retardation factor (a ratio of the velocity of the contaminant to that of water) is<br />

measured directly from the experimental data. A K d value can be calculated from the retardation<br />

factor. It is frequently useful to compare the back-calculated K d value from these experiments<br />

with those derived directly from the batch experiments to evaluate the influence of limited<br />

interaction between solid and solution imposed by the flow-through system.<br />

One potential advantage of the flow-through column studies is that the retardation factor can be<br />

inserted directly into the transport code. However, if the study site contains different hydrological<br />

conditions (e.g., porosity and bulk density) than the column experiment, than a K d value needs to<br />

be calculated from the retardation factor. Another advantage is that the column experiment<br />

provides a much closer approximation of the physical conditions and chemical processes<br />

occurring in the field site than a batch sorption experiment. Column experiments permit the<br />

investigation of the influence of limited spatial and temporal (nonequilibium) contact between<br />

solute and solid have on contaminant retardation. Additionally, the influence of mobile colloid<br />

facilitated transport and partial saturation can be investigated. A third advantage is that both<br />

adsorption or desorption reactions can be studied. The predominance of 1 mechanism of<br />

adsorption or desorption over another cannot be predicted a priori and therefore generalizing the<br />

results from 1 set of laboratory experimental conditions to field conditions is never without some<br />

uncertainty. Ideally, flow-through column experiments would be used exclusively for determining<br />

K d values, but equipment cost, time constraints, experimental complexity, and data reduction<br />

uncertainties discourage more extensive use.<br />

3.3 Other Methods<br />

Less commonly used methods include the K oc method, in-situ batch method, and the field<br />

modeling method. The K oc method is a very effective indirect method of calculating K d values,<br />

however, it is only applicable to organic compounds. The in-situ batch method requires that<br />

paired soil and groundwater samples be collected directly from the aquifer system being modeled<br />

and then measuring directly the amount of contaminant on the solid and liquid phases. The<br />

advantage of this approach is that the precise solution chemistry and solid phase mineralogy<br />

existing in the study site is used to measure the K d value. However, this method is not used often<br />

because of the analytical problems associated with measuring the exchangeable fraction of<br />

contaminant on the solid phase. Finally, the field modeling method of calculating K d values uses<br />

groundwater monitoring data and source term data to calculate a K d value. One key drawback to<br />

this technique is that it is very model dependent. Because the calculated K d value are model<br />

dependent and highly site specific, the K d values must be used for contaminant transport<br />

calculations at other sites.<br />

3.4 Issues<br />

A number of issues exist concerning the measurement of K d values and the selection of K d values<br />

from the literature. These issues include: using simple versus complex systems to measure K d<br />

values, field variability, the “gravel issue,” and the “colloid issue.” Soils are a complex mixture<br />

3.2

containing solid, gaseous, and liquid phases. Each phase contains several different constituents.<br />

The use of simplified systems containing single mineral phases and aqueous phases with 1 or 2<br />

dissolved species has provided valuable paradigms for understanding sorption processes in more<br />

complex, natural systems. However, the K d values generated from these simple systems are<br />

generally of little value for importing directly into transport models. Values for transport models<br />

should be generated from geologic materials from or similar to the study site. The “gravel issue”<br />

is the problem that transport modelers face when converting laboratory-derived K d values based<br />

on experiments conducted with the 2 mm in size. No standard methods exist to address this issue. There are<br />

many subsurface soils dominated by cobbles, gravel, or boulders. To base the K d values on the<br />

2-mm fraction and the extent of the sorption is proportional to the surface area. The<br />

underlying assumptions in this approach are that the mineralogy is similar in the less than 2- and<br />

greater than 2-mm fractions and that the sorption processes occurring in the smaller fraction are<br />

similar to those that occur in the larger fraction.<br />

Spatial variability provides additional complexity to understanding and modeling contaminant<br />

retention to subsurface soils. The extent to which contaminants partition to soils changes as field<br />

mineralogy and chemistry change. Thus, a single K d value is almost never sufficient for an entire<br />

study site and should change as chemically important environmental conditions change. Three<br />

approaches used to vary K d values in transport codes are the K d look-up table approach, the<br />

parametric-K d approach, and the mechanistic K d approach. The extent to which these approaches<br />

are presently used and the ease of incorporating them into a flow model varies greatly.<br />

Parametric-K d values typically have limited environmental ranges of application. Mechanistic K d<br />

values are limited to uniform solid and aqueous systems with little application to heterogenous<br />

soils existing in nature. The easiest and the most common variable-K d model interfaced with<br />

transport codes is the look-up table. In K d look-up tables, separate K d values are assigned to a<br />

matrix of discrete categories defined by chemically important ancillary parameters. No single set<br />

of ancillary parameters, such as pH and soil texture, is universally appropriate for defining<br />

categories in K d look-up tables. Instead, the ancillary parameters must vary in accordance to the<br />

geochemistry of the contaminant. It is essential to understand fully the criteria and process used<br />

for selecting the values incorporated in such a table. Differences in the criteria and process used<br />

to select K d values can result in appreciable different K d values. Examples are presented in this<br />

volume.<br />

Contaminant transport models generally treat the subsurface environment as a 2-phase system in<br />

which contaminants are distributed between a mobile aqueous phase and an immobile solid phase<br />

3.3

(e.g., soil). An increasing body of evidence indicates that under some subsurface conditions,<br />

components of the solid phase may exist as colloids 1 that may be transported with the flowing<br />

water. Subsurface mobile colloids originate from (1) the dispersion of surface or subsurface soils,<br />

(2) decementation of secondary mineral phases, and (3) homogeneous precipitation of groundwater<br />

constituents. Association of contaminants with this additional mobile phase may enhance<br />

not only the amount of contaminant that is transported, but also the rate of contaminant transport.<br />

Most current approaches to predicting contaminant transport ignore this mechanism not because<br />

it is obscure or because the mathematical algorithms have not been developed, but because little<br />

information is available on the occurrence, the mineralogical properties, the physicochemical<br />

properties, or the conditions conducive to the generation of mobile colloids. There are 2 primary<br />

problems associated with studying colloid-facilitated transport of contaminants under natural<br />

conditions. First, it is difficult to collect colloids from the subsurface in a manner which<br />

minimizes or eliminates sampling artifacts. Secondly, it is difficult to unambiguously delineate<br />

between the contaminants in the mobile-aqueous and mobile-solid phases.<br />

Often K d values used in transport models are selected to provide a conservative estimate of<br />

contaminant migration or health effects. However, the same K d value would not provide a<br />

conservative estimate for clean-up calculations. Conservatism for remediation calculations would<br />

tend to err on the side of underestimating the extent of contaminant desorption that would occur<br />

in the aquifer once pump-and-treat or soil flushing treatments commenced. Such an estimate<br />

would provide an upper limit to time, money, and work required to extract a contaminant from a<br />

soil. This would be accomplished by selecting a K d from the upper range of literature values.<br />

It is incumbent upon the transport modeler to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the<br />

different K d methods, and perhaps more importantly, the underlying assumption of the methods in<br />

order to properly select K d values from the literature. The K d values reported in the literature for<br />

any given contaminant may vary by as much as 6 orders of magnitude. An understanding of the<br />

important geochemical processes and knowledge of the important ancillary parameters affecting<br />

the sorption chemistry of the contaminant of interest is necessary for selecting appropriate K d<br />

value(s) for contaminant transport modeling.<br />

1 A colloid is any fine-grained material, sometimes limited to the particle-size range of<br />

4.0 Application of Chemical Reaction Models<br />

Computerized chemical reaction models based on thermodynamic principles may be used to<br />

calculate processes such as aqueous complexation, oxidation/reduction, adsorption/desorption,<br />

and mineral precipitation/dissolution for contaminants in soil-water systems. The capabilities of a<br />

chemical reaction model depend on the models incorporated into its computer code and the<br />

availability of thermodynamic and/or adsorption data for aqueous and mineral constituents of<br />

interest. Chemical reaction models, their utility to understanding the solution chemistry of<br />

contaminants, and the M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 model in particular are described in detail in Chapter 5 of<br />

Volume I.<br />

The M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 computer code is an equilibrium chemical reaction model. It was developed<br />

with EPA funding by originally combining the mathematical structure of the M<strong>IN</strong>EQL code with<br />

the thermodynamic database and geochemical attributes of the WATEQ3 code. The M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2<br />

code includes submodels to calculate aqueous speciation/complexation, oxidation-reduction, gasphase<br />

equilibria, solubility and saturation state (i.e., saturation index), precipitation/dissolution of<br />

solid phases, and adsorption. The most current version of M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 available from EPA is<br />

compiled to execute on a personal computer (PC) using the MS-DOS computer operating system.<br />

The M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 software package includes PRODEFA2, a computer code used to create and<br />

modify input files for M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2.<br />

The M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 code contains an extensive thermodynamic database for modeling the speciation<br />

and solubility of contaminants and geologically significant constituents in low-temperature, soilwater<br />

systems. Of the contaminants selected for consideration in this project [chromium,<br />

cadmium, cesium, tritium ( 3 H), lead, plutonium, radon, strontium, thorium, and uranium], the<br />

M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 thermodynamic database contains speciation and solubility reactions for chromium,<br />

including the valence states Cr(II), Cr(III), and Cr(VI); cadmium; lead; strontium; and uranium,<br />

including the valence states U(III), U(IV), U(V), and U(VI). Some of the thermodynamic data in<br />

the EPA version have been superseded in other users’ databases by more recently published data.<br />

The M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 code includes 7 adsorption model options. The non-electrostatic adsorption<br />

act<br />

models include the activity <strong>Kd</strong> , activity Langmuir, activity Freundlich, and ion exchange models.<br />

The electrostatic adsorption models include the diffuse layer, constant capacitance, and triple<br />

layer models. The M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 code does not include an integrated database of adsorption<br />

constants and reactions for any of the 7 models. These data must be supplied by the user as part<br />

of the input file information.<br />

Chemical reaction models, such as the M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 code, cannot be used a priori to predict a<br />

partition coefficient, K d, value. The M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 code may be used to calculate the chemical<br />

changes that result in the aqueous phase from adsorption using the more data intensive,<br />

electrostatic adsorption models. The results of such calculations in turn can be used to back<br />

calculate a K d value. The user however must make assumptions concerning the composition and<br />

mass of the dominant sorptive substrate, and supply the adsorption parameters for surface-<br />

4.1

complexation constants for the contaminants of interest and the assumed sorptive phase. The<br />

EPA (EPA 1992, 1996) has used the M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2 model and this approach to estimate K d values<br />

for several metals under a variety of geochemical conditions and metal concentrations to support<br />

several waste disposal issues. The EPA in its “Soil Screening Guidance” determined<br />

M<strong>IN</strong>TEQA2-estimated K d values for barium, beryllium, cadmium, Cr(III), Hg(II), nickel, silver,<br />

and zinc as a function of pH assuming adsorption on a fixed mass of iron oxide (EPA, 1996; RTI,<br />

1994). The calculations assumed equilibrium conditions, and did not consider redox potential or<br />

metal competition for the adsorption sites. In addition to these constraints, EPA (1996) noted<br />

that this approach was limited by the potential sorbent surfaces that could be considered and<br />

availability of thermodynamic data. Their calculations were limited to metal adsorption on iron<br />

oxide, although sorption of these metals to other minerals, such as clays and carbonates, is well<br />

known.<br />

Typically, the data required to derive the values of adsorption parameters that are needed as input<br />

for adsorption submodels in chemical reaction codes are more extensive than information reported<br />

in a typical laboratory batch K d study. If the appropriate data are reported, it is likely that a user<br />

could hand calculate a composition-based K d value from the data reported in the adsorption study<br />

without the need of a chemical reaction model.<br />

Chemical reaction models can be used, however, to support evaluations of K d values and related<br />

contaminant migration and risk assessment modeling predictions. Chemical reaction codes can be<br />

used to calculate aqueous complexation to determine the ionic state and composition of the<br />

dominant species for a dissolved contaminant present in a soil-water system. This information<br />

may in turn be used to substantiate the conceptual model being used for calculating the adsorption<br />

of a particular contaminant. Chemical reaction models can be used to predict bounding,<br />

technically defensible maximum concentration limits for contaminants as a function of key<br />

composition parameters (e.g., pH) for any specific soil-water system. These values may provide<br />

more realistic bounding values for the maximum concentration attainable in a soil-water system<br />

when doing risk assessment calculations. Chemical reaction models can also be used to analyze<br />

initial and final geochemical conditions associated with laboratory K d measurements to determine<br />

if the measurement had been affected by processes such as mineral precipitation which might have<br />

compromised the derived K d values. Although chemical reaction models cannot be used to<br />

predict K d values, they can provide aqueous speciation and solubility information that is<br />

exceedingly valuable in the evaluation of K d values selected from the literature and/or measured in<br />

the laboratory.<br />

4.2

5.0 Contaminant Geochemistry and K d Values<br />

The important geochemical factors affecting the sorption 1 of cadmium (Cd), cesium (Cs),<br />

chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), plutonium (Pu), radon (Rn), strontium (Sr), thorium (Th), tritium ( 3 H),<br />

and uranium (U) are discussed in this chapter. The objectives of this chapter are to: (1) provide a<br />

“thumb-nail sketch” of the key geochemical processes affecting sorption of these contaminants,<br />

(2) provide references to key experimental and review articles for further reading, (3) identify the<br />

important aqueous- and solid-phase parameters controlling contaminant sorption in the subsurface<br />

environment, and (4) identify, when possible, minimum and maximum conservative K d values for<br />

each contaminant as a function key geochemical processes affecting their sorption.<br />

5.1 General<br />

Important chemical speciation, (co)precipitation/dissolution, and adsorption/desorption processes<br />

of each contaminant are discussed. Emphasis of these discussions is directed at describing the<br />

general geochemistry that occurs in oxic environments containing low concentrations of organic<br />

carbon located far from a point source (i.e., in the far field). These environmental conditions<br />

comprise a large portion of the contaminated sites of concern to the EPA, DOE, and/or NRC.<br />